Under the new tax law, each state selected 25 percent of its low-income census tracts, as defined under the New Markets Tax Credit program, to be OZs. States were also able to designate up to 5 percent of tracts contiguous to low-income tracts as qualifying areas. The OZs will remain fixed from the date of designation through the close of the tenth calendar year and can be quickly identified on mapping websites.

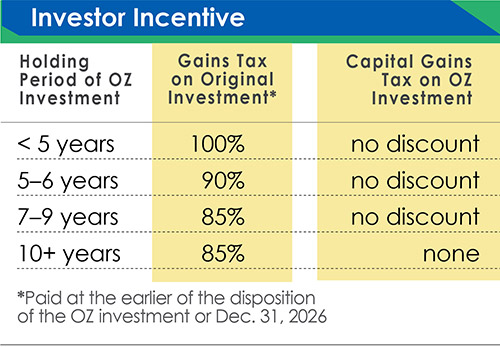

Investor Incentive

Investors initially benefit from deferral of capital gains tax, which effectively becomes an interest-free loan from the federal government to fund approximately 20 percent of the OZ investment. The capital gains tax on the original investment is due at the earlier of the disposition of the OZ investment or with the federal tax return covering Dec. 31, 2026. The capital gains tax on the original investment is reduced 10 percent if the OZ investment is held for five years and another 5 percent (15 percent in total) if held seven years or longer. The greatest incentive though is to hold the OZ investment for 10 years, which results in no capital gains tax on the new OZ investment, including the potential for no recapture of depreciation taken during the 10-year holding period.

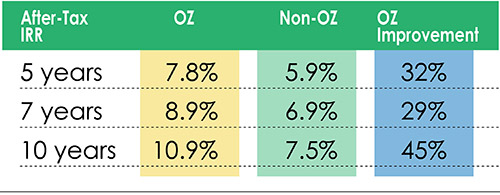

Though the tax benefit accrues to the investor, developers planning projects within OZs can share in the benefit through careful attention to the investment structure. Developers seeking OZ capital can target cash returns and tax attributes (e.g., depreciation losses) between classes of investors that consist of OZ investors, non-OZ investors, those that can (or cannot) use passive losses, and the general partner (developer) through special allocations in the operating agreement. A carefully structured operating agreement will “expand the pie” by allowing the developer to retain a greater share of cash and/or tax losses, while OZ investors experience greater after-tax returns — the classic win-win.

The OZ tax benefit accommodates a shift of cash returns and tax losses toward the developer, while still enhancing the yield for OZ investors. Savvy developers will need to offer a reasonable combination of cash returns and appreciation to attract OZ investors. Given the current capital gains tax rate, investors will not take excessive risk or substantially inferior cash returns and participation in appreciation to simply capture the deferral and reduction benefit on the original gain. They will need to see potential to take depreciation (to the extent allowed) and participate in the appreciation of the investment to benefit from the elimination of gains on the new OZ investment.

In the following example, investors eligible for OZ treatment achieve an internal rate of return (IRR) 45 percent higher than investors not qualifying for OZ benefits, and this is before value-engineering the structure to specially allocate depreciation.On October 19, 2018, the U.S. Treasury released regulations that will guide governance and implementation of OZs. The regulations answered many questions but left several important open questions.

- The regulations broadly define “gain” to allow short- and long-term capital gains. Gains from real estate, securities, the sale of a business, among others are eligible. In contrast to a section 1031 exchange, where all of the proceeds from the sale of real estate must be reinvested into real estate to achieve a deferral, only the gain portion needs to be reinvested within a Qualified Opportunity Zone (QOZ). Additionally, there is no “like kind” requirement, so an investor harvesting gains from the stock market could receive OZ benefits by investing gains into real estate in a QOZ.

- Deferred gains retain their original nature, which means that gains invested in an OZ will retain their original tax attributes. For example, a short-term capital gain will retain its character when reported on a future tax return when the original deferred gain is due (the earlier of Dec. 31, 2026 or upon disposition of the new OZ investment).

- Qualified Opportunity Funds (QOFs) can be invested as common or preferred equity in a partnership or corporation or can be invested directly in QOZ business assets. Since 90 percent of a QOF’s assets must be invested in QOZ property (defined as tangible property), deploying more than 10 percent of the QOF’s capital as a loan to a QOZ business is prohibited.

- Generally, a QOF must invest funds into QOZ property within six months. However, when investing in a QOZ business, financial property held for construction or rehabilitation may be held for a period of up to 31 months, if there is a written plan that identifies the financial property as property held for the acquisition, construction or substantial improvement of tangible property in the Opportunity Zone. Note that there is no guidance on how specific the “plan” must be to satisfy this requirement.

- While 90 percent of a QOF’s assets must be invested in QOZ property or business within six months from the date received, the QOZ business only needs to hold 70 percent of its owned and leased tangible property within an OZ, which allows some flexibility for the business to have more than one location and/or maintain a portion of its assets outside of the OZ.

- Further, 50 percent of the gross income of a QOZ business must be derived from the active conduct of a trade or business in the QOZ. These requirements may be problematic for businesses where their assets and/or personnel conduct business outside of the OZ (e.g., a landscaping company or other contracting businesses that generate revenue offsite).

- To satisfy the “substantial improvement” requirement of acquired property, the basis attributable to land on which an acquired building sits is not taken into account in determining whether the building has been substantially improved. For example, a QOF acquires land and building for $10 million, where $3 million is allocated to land. Another $7 million must be invested to satisfy the substantial improvement requirement.

- An investor may liquidate its entire interest in a QOF before Dec. 31, 2028 (expiration date of QOZ census tracts) and reinvest into another QOZ project within 180 days (subject to substantial improvement and all other requirements) to maintain all original deferral benefits. What is not clear is if the underlying QOZ business can be sold with the proceeds reinvested by the QOF into another QOZ business.

- The following trades or businesses cannot qualify as a QOZ business: (i) any private or commercial golf course, (ii) country club, (iii) massage parlor, (iv) hot tub facility, (v) suntan facility, (vi) racetrack or other facility used for gambling, or (vii) any store the principal business of which is the sale of alcoholic beverages for consumption off-premises.

- The step-up in basis after 10 years appears to be inclusive of accelerated depreciation. For example, a property acquired for $10 million that appreciates at 4 percent per year is sold for $14.8 million after 10 years, and has a tax basis of $6 million after taking $4 million of accelerated depreciation (assuming cash distributions equal taxable income for simplicity). The step-up election to $14.8 million would eliminate the gain of $8.8 million.

- The proposed regulations permit taxpayers to make the basis step-up election after a QOZ designation expires. The ability to make this election is preserved under these proposed regulations until Dec. 31, 2047, but as currently drafted requires an actual disposition to a third party to receive the step-up in basis. The IRS recognizes this may create an unintended consequence to incentivize sub-optimal dispositions of QOZ investments and is seeking other options to address this issue.

- Can an Opportunity Fund have debt-financed distributions? Or does that constitute an exchange that ends the investment’s tax benefits?

- What actions of a QOF lead to decertification? The guidance indicates the Treasury and the IRS intend to publish additional proposed regulations to address conduct that leads to decertification of a QOF.

- While the “substantially all” test for QOZ business property held by an OZ business was set at 70 percent, the definition of substantially all for other rules was left undefined.

- What does “additions to basis with respect to such property” mean? Can a second building or improvement qualify?

- Can an Opportunity Fund lend capital? Or is lending limited since the Opportunity Fund must have 90 percent of its assets invested in qualified OZ property, which is defined as tangible property?