The Projections

Oxford Economics forecasts project that over the next 10 years, manufacturing output is expected to increase by 3.4 percent annually, as compared to 2.7 percent for the economy as a whole. That means that manufacturing is expected to make an increasingly large contribution toward positive U.S. economic growth. In fact, the share of manufacturing output in GDP is projected to increase from 12.7 percent (2013) to 13.7 percent (2023). By the measure of output, therefore, manufacturing is expected to be an engine of economic growth over the next 10 years.

In part, the dichotomy between employment and output can be explained by observing that many low-skill, labor-intensive industries remain highly vulnerable to continued offshoring or automation (apparel-related industries, for example). But the fact is that even fast-growing advanced manufacturing industries are expected to show continued, albeit modest, employment declines. This can be clearly demonstrated by the following three examples:

- Computer and electronic product manufacturing: Output is expected to accelerate to 4.3 percent per year during the decade; yet forecasts indicate employment will fall by 142,300 by 2022.

- Computer and peripheral equipment manufacturing: This sector is expected to have the fastest growth in real output among all industries (9.2 percent annually); yet employment is projected to decline by 39,900 by 2022.

- Semiconductor and other electronic components: Again, BLS says output is expected to grow by 4.1 percent annually, while employment falls by 31,200 by 2022.

For two reasons, the focus on output growth is probably a more reliable indicator of manufacturing’s rising economic importance than employment projections. The first reason, substantiated in economic literature, is that manufacturing has one of the highest economic multipliers of any industry (in this context the economic multiplier is the estimated number by which the amount of capital investment by a company is “multiplied” to give the total amount of economic activity created). According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, each $1.00 of investment by a manufacturing company actually results in $1.33 of economic activity when the “spillover” effects of that investment are considered. Output growth probably captures the industry’s very high economic multiplier effect more accurately than does direct employment alone.

One final observation on the importance of manufacturing: Oxford Economics forecasts the economic performance of over 3,500 cities globally. In the United States, one of the greatest predictors of strong economic growth in our metro level forecast models is a strong concentration of advanced manufacturing. The more advanced manufacturing in a region, the more likely that that region will be at the high end of these economic forecasts.

Obsolescence Necessitates Accelerated Capital Spending

Aging physical plant has been a key driver behind several recent industrial relocation projects. Industrial moves are exceptionally disruptive to operations and hence take place very infrequently. More typically, as plants grow, managers and owners tend to improvise solutions — e.g., a storage area is added where space allows rather than where workflow dictates; or perhaps production gets split between adjacent facilities rather than consolidated under one roof. At some point, these inefficiencies, plus the cost of maintaining aging plant and equipment, begin to severely compromise the competiveness of the operation and a relocation project becomes necessary. This issue of aging and obsolete plant and equipment will likely be a key motivation behind many upcoming projects.

Oxford Economics estimates that the average age of structures in the United States (nonresidential real estate plus other large industrial equipment classes) is currently at its highest since the 1960s. Replacing these aging assets will be a significant contributor to an expected acceleration in capital spending expenditures, and that will include major new investments in manufacturing facilities.

It might be a bit counterintuitive to observe that once a manufacturer decides to move, its potential search area is often larger than a more basic/labor-intensive operation. That’s because once committed to a move, there is (within reason) little marginal cost associated with moving an extra couple of hundred miles. The opportunity to reduce or improve utility costs, regulatory environment, or physical plant is typically far greater than the costs to retain and relocate key plant managers and supervisors. Still another reason why manufacturing search areas might be greater than expected is the absence of suitable real estate product on the market.

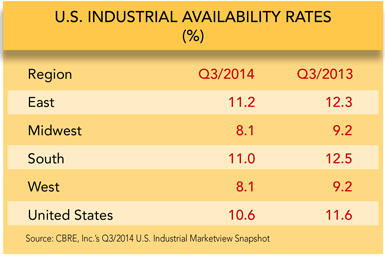

Finding industrial space is already challenging and will likely get more so as the economy improves. In addition, much of the vacant industrial space on the market is often aged or otherwise obsolete. CBRE, Inc. reports that there have now been 18 straight quarters of positive net absorption in the United States industrial market and that industrial vacancy rates are now declining throughout the United States (Figure 3).

Retention and Attraction: Opportunities and Strategies

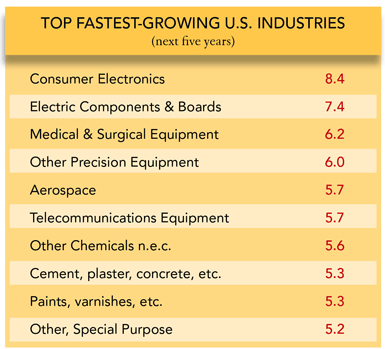

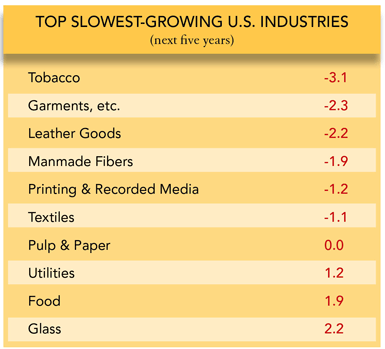

Growing output and aging plant would seem to portend lots of relocation activity. But which industries are expected to experience the strongest growth and which might decline? Based upon Oxford Economics’ forecast of key industries, the industries in figures 1 and 2 are expected to be the fastest-growing or fastest-declining manufacturing industries over the next five years (annual percentages changes, 2010 prices).

As communities seek to recruit or retain these potential manufacturing relocation projects, what strategies might they consider? One important differentiator in these projects is the distinction between advanced and basic manufacturing. Most new industrial space being built today seems to be targeted toward advanced manufacturing — the same part of the manufacturing sector that is most often included in a state’s target industries (i.e., benefit from enhanced incentives). This makes sense as one recalls that a concentration of advanced manufacturing is among the most important indicators of metro-level economic growth.

Those states that recognize the importance of attracting and retaining lower-skilled basic manufacturing jobs might want to reexamine (if applicable) the often-heavy reliance on wages as a measure of project desirability. Projects creating opportunity for lower-skilled workers serve important (and very large segments) of most communities’ populations. Regardless of the level of state support, it is often local economic development efforts that can be the deciding factor in whether a community retains an existing facility or wins a new project.

Industrial relocation projects have huge year-one cash-outflow requirements — inventory needs to be stockpiled, operations disassembled and then reassembled, etc. At the same time, the new facility often needs significant improvements to meet project requirements. As examples, one recent project required installation of an on-site freezer with back-up generator; another needed the facility to be fitted with wastewater treatment equipment to manage sewage and water costs. Local economic development officials working with responsive local developers made a world of difference in helping address these challenges. Local partners are often the ones best positioned to identify grants and other financing mechanisms needed to help capitalize the cost of specialized facility improvements.