Incentives in the New Economy

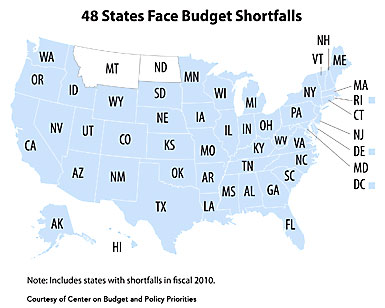

What does the future of economic development incentives look like with so many states facing major budgetary challenges?

Nov 09

Budget shortfalls make some incentives funds more scarce; however, the need for job creation forces states to try harder than ever to attract jobs and investment. While it may seem counter-intuitive to some, many states are actually becoming more aggressive with the incentive programs they are creating. What is evident is that regardless of the economic outlook or budget constraints of a particular state, economic development organizations are being forced to come up with more creative, better targeted, and more responsible incentive programs in order to continue attracting jobs.

Politics Behind Programs

Despite hard economic times and budget shortfalls, many states are finding it politically important to do something, even if the long-term effect cannot be determined. Some states have adopted a proactive approach to the economic impact of the job losses. New Jersey's Governor Jon Corzine, for example, created the InvestNJ Program in December 2008, which awarded $3,000 per new job created anywhere in the state, even though New Jersey was in the throes of major budget shortfalls. While some have argued that certain new economic programs are politically-driven - Corzine was in a re-election campaign - others have applauded the fact that the state was willing to adopt creative solutions to help attract new jobs.

Kansas' approach is interesting in that they are carefully focusing on where their incentives are going to be directed. Officials have created a new program in the Promoting Employment Across Kansas (PEAK) program, but have only made it eligible for a business that is moving operations from outside of Kansas into the state, as opposed to a Kansas company that is looking to expand. Also, the state has cut back on its existing incentive programs and has told existing companies that they can only receive 90 percent of promised incentives until the budget gap is addressed.

There have been a number of questions related to the enactment of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) as it relates to business incentives. Many companies and consumers alike are frustrated by the fact that the hundreds of billions of federal stimulus dollars that the states have received from ARRA to stimulate jobs have instead been funneled to simply balance state's budgets. Also frustrating is the difficulty in accessing the federal programs. For example, not all states have determined how the ARRA funds will be utilized. For those states that have outlined programs for the ARRA funds, they have not yet determined administrative guidelines, so companies are still unsure whether those programs will have a value to them. For now, most companies are benefiting from ARRA funds through highly targeted programs, such as grants and loans for renewable energy projects, or through existing but refortified programs such as community development block grants.

ROI, Accountability, and Transparency

Whether it's a new or existing incentive, many programs around the country have recently required greater accountability and return on investment (ROI). For example, New York's Empire Zone program now mandates that businesses pass a 20:1 cost/benefit ratio, requiring a $20 economic return for every $1 in incentives; that's up from a 15:1 ratio. For programs that are coming under fire from a state's legislature, like the Empire Zone program, there will continue to be a trend towards greater accountability and ROI.

States that are offering deal-closing funds are widely coveted; however, many deal-closing funds are either shrinking or not receiving annual allocations. Illinois, for example, has been unsuccessful for several years now re-funding its governor's closing fund. Those states that do continue to offer closing funds (despite budget shortfalls) have seen an increase in the number of shortlisted projects. With deal-closing funds scarce, post-performance incentives are what states are touting; these programs don't take from existing budgets, but instead offer incentives based on a portion of the net new revenue to the state. Since these types of incentives do not "cost" the state - i.e., they are fiscally neutral or net revenue generators for the state - these post-performance incentive programs are becoming more common and more lucrative.

A good example of self-funding incentive programs are those that offer withholding tax rebates for new job creation. This type of non-income tax-based incentive can have significant value for companies that do not have large tax liabilities in the state where they are contemplating job growth.

With respect to transparency, the recent economic upheaval has placed many incentive programs under closer scrutiny. Not only are deals being reviewed more closely during the negotiation phase - often times requiring a greater cost/benefit ratio, for example - there is greater accountability and more tracking during the compliance phase. Michigan recently passed legislation to extend tax incentive programs that had previously run out of funding. It did so, however, with a caveat: in exchange for authorizing an additional allotment of tax credits, the Michigan Economic Development Corporation would now have to report pertinent post-incentive award information, such as job creation and/or retention. Michigan had previously required less reporting on this information due to privacy restrictions.

Finally, the inclusion of clawbacks in incentive agreements remains strong. Clawbacks require a company to return some or all of the incentive if it fails to meet its agreed upon job commitment. If the language of the clawback is determined by either statute, it can sometimes be difficult to omit and/or change in the agreement; however, this is not always the case and sometimes the language can be changed to something more equitable for both sides. In these economically challenging times, states may look to enforce clawbacks as a way to plug budget holes, but doing so will cause greater economic harm to a company that may be struggling to keep its facility open.

State Incentive Trends

Some states don't have the legislative will to create new programs, so they instead have retooled their existing incentive programs to make them both more lucrative and more user-friendly. By simply lowering the requisite job threshold numbers and/or capital investment required, states such as Tennessee and Georgia, for example, are enabling more companies to access the programs. In light of many states' budget shortfalls, "tweaking" existing programs is often an easier legislative and political sell than passing brand new incentive program legislation.

We have also seen a distinct trend in the creation of lucrative incentive programs for targeted industries. Typically these industries have high-paying wages and/or tie into a cluster that the state is looking to promote and grow. Many feel that this trend is positive, as it targets industries that are well-suited to the local communities and economies - and can help to create clusters within the supply chain.

Experts have also noticed a trend towards enabling credits to be refunded, sold, or transferred if a company cannot utilize the credits themselves. Statutes that allow for saleable or transferable tax credits are found in a number of states, including Missouri and Oregon. These credits can be valuable to a company that is in a net operating loss position in a particular state, as well as startup companies. These credits enable companies - many of which have just survived two tough economic years in a row and do not have the tax liability in a particular state - to allow for the sale and/or transfer of the tax credits to qualified companies that can utilize them. They in return receive cash which can then be used to reinvest into the business.

Consultants often advise economic development agencies, both at the state and local level, to "mind their own back yard," reminding them of the idea that "a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush." Local communities have taken heed and have been increasing their retention programs with companies by going door-to-door to local businesses. Most job growth comes from homegrown companies, and while attracting new companies to the state often creates a splash, in order to thrive, it's the jobs that are grown from within that are going to be a state's bread and butter. Just as big new outside deal announcements are positive public relations for a state, announcements of jobs leaving a state can be public relations nightmares. With a majority of U.S. companies "rightsizing" or consolidating operations, we expect job retention to remain a growing priority for economic development departments.

There is an old adage, "incentives don't make a bad deal good, they make a good deal better"; this still holds true, even in this economic climate. It is clear that incentives will continue to play an important, if not critical role, for some businesses' location and project decisions, and that despite budget shortfalls, states must continue to offer incentives to companies to help stimulate economic growth. The future of incentive programs is clearly being shaped by this new environment and those states that are prepared to innovate will be the beneficiaries.

Kathy Mussio is managing partner at Atlas Insight, LLC. She has more than 15 years of combined experience as an entrepreneur and management consultant in the site selection and incentive negotiation businesses. She can be reached via e-mail at kmussio@atlasinsight.com.

Project Announcements

Siemens Energy Plans Fort Payne, Alabama, Manufacturing Operations

02/09/2026

Preciball USA Plans Screven County, Georgia, Production Operations

02/09/2026

Mecad USA Plans Tulsa Port of Catoosa, Oklahoma, Manufacturing Campus

02/08/2026

Anduril Industries Plans Long Beach-Lakewood, California, Operations

02/08/2026

Dongwon Autopart Technology Plans Emanuel County, Georgia, Production Operations

02/07/2026

Quantum Machines Plans Chicago, Illinois, Operations

02/06/2026

Most Read

-

Data Centers in 2025: When Power Became the Gatekeeper

Q4 2025

-

Top States for Doing Business in 2024: A Continued Legacy of Excellence

Q3 2024

-

Speed Built In—The Real Differentiator for 2026 Site Selection Projects

Q1 2026

-

Preparing for the Next USMCA Shake-Up

Q4 2025

-

Tariff Shockwaves Hit the Industrial Sector

Q4 2025

-

The New Industrial Revolution in Biotech

Q4 2025

-

Strategic Industries at the Crossroads: Defense, Aerospace, and Maritime Enter 2026

Q1 2026