The Growth of Indoor and Vertical Farming

In an attempt to deal with the vagaries of weather and changing climate, farmers are turning to vertical and other high-tech indoor farms.

Q1 2023

One is Morehead, Ky., where AppHarvest has opened a 2.76-million-square-foot high-tech greenhouse to grow non-GMO, chemical pesticide-free fruits and vegetables closer to consumers. AppHarvest has also broken ground on a second similarly sized, controlled-environment ag facility nearby in Richmond, Ky.

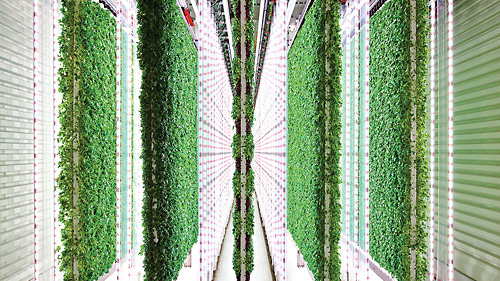

Meanwhile, in Luzerne County Pa., Upward Farms, a Brooklyn-based indoor aquaponics company, is building a 250,000-square-foot vertical farm facility, where crops are grown in vertically stacked layers. The county has also been chosen by Crop One for its third U.S. vertical farming operation, which will comprise 316,000 square feet.

Another massive vertical farming campus is planned by San Francisco-based Plenty Unlimited Inc. at the Meadowville Technology Park in Chesterfield County, Va. To be built in six phases, it will encompass 200,000 square feet and is projected to eventually produce 20 million pounds of produce annually.

An Attempt to Remove the Risk

For decades, farming has been one of the most financially risky professions. Now, in response to several converging trends — consumer demand for locally grown food, an increasing population, and shrinking arable land — entrepreneurs are removing some of the risk by growing crops indoors, either in so-called vertical farms or in high-tech greenhouses that enable growing in any climate. As the technology has advanced, these indoor operations have been attracting more investment capital and becoming larger.

“There is a tremendous amount of experimentation going on,” says Kevin Kimle, Rastetter Chair of Agricultural Entrepreneurship at Iowa State University and director of the Start Something College of Agriculture and Life Sciences program. “There is hardly an ag tech area where there isn’t some sort of play on this going on.”

Like any nascent, entrepreneurial industry, vertical farming has had failures as people figure out what will work, says Kimle. The 2020 pandemic was a major setback for a number of smaller indoor growing operations, since restaurants and corporate kitchens were abruptly shut down, Kimle points out. For example, Clayton Farms, an operation owned by ISU lost 95 percent of its business “overnight,” he says.

One of the major challenges to startups is the high capital expenditures for labor and energy. The industry has continued to attract investment capital, “but for every success there are probably one or two startups that didn’t work. Sometimes the founders love the technology but forget that at the end of the day it’s still farming,” Kimle says. “Our existing ag production is really efficient, so you have to have something that is — from a cost perspective — in the range of what people are accustomed to paying. If you don’t, you really need a differentiated product,” for example, some kind of “artisan” greens, he explains.

The industry is at the “venture growth stage — a lot of emerging technologies and venture-backed businesses with unique intellectual property,” says Djavid Amidi-Abraham, director of consulting for Agritecture, a Brooklyn, N.Y.-based consulting and tech firm. “We’re still in a very risky business environment. It’s similar to other technology boom-and-bust cycles.”

Modern, large-scale greenhouses can work in any climate, he says. “The biggest limitation is that in certain hot and mild climates — such as South Florida — they are less efficient. While greenhouses require more square footage, the access to free energy (the sun) is a major advantage over vertical farming. Power use per unit of yield is much lower.” He says one of the major challenges to startups is the high capital expenditures for labor and energy. Regarding labor “there is a big push” to reduce workforce requirements through improved technology, including automation. On the market side, more widespread adoption of indoor-grown produce by large-scale buyers (retailers and wholesalers) would mean more market demand, he says.

Amidi-Abraham says indoor farming is not a one-stop solution for every farmer, business, or city. “Nor is any one solution in urban agriculture the best.” The most fitting urban farming solution truly depends on the city, the culture, and the people involved.”

Project Announcements

Poland-Based JGB Brothers Plans Bamberg County, South Carolina, Production Operations

01/23/2026

Lithium Battery Company Plans Tampa, Florida, Battery Pack Production Operations

01/10/2026

Germany-Based Silesia Flavors Establishes Huntley, Illinois, Production Operations

01/08/2026

Edelweiss Dairy Expands Freedom, New York, Operations

12/24/2025

Swire Coca-Cola, USA Plans Colorado Springs, Colorado, Production Operations

12/22/2025

Kroger Plans Simpson County, Kentucky, Distribution Operations

12/19/2025

Most Read

-

Top States for Doing Business in 2024: A Continued Legacy of Excellence

Q3 2024

-

Data Centers in 2025: When Power Became the Gatekeeper

Q4 2025

-

Speed Built In—The Real Differentiator for 2026 Site Selection Projects

Q1 2026

-

Preparing for the Next USMCA Shake-Up

Q4 2025

-

Tariff Shockwaves Hit the Industrial Sector

Q4 2025

-

The New Industrial Revolution in Biotech

Q4 2025

-

Strategic Industries at the Crossroads: Defense, Aerospace, and Maritime Enter 2026

Q1 2026