“These days, it’s no longer enough for companies simply to have highly efficient product flow from origin to business destination,” says Will O’Shea, chief sales and marketing officer of XPO Last Mile, the country’s largest provider of last-mile heavy goods delivery. “If they can’t be equally adept at delivering their goods to end consumers when those consumers want them, they run a significant risk of losing revenue to other companies that can.” One of Area Development’s field editors recently spoke with O’Shea about why agile home delivery has become such a game-changer — and how it could permanently blur the lines between companies’ manufacturing locations, distribution networks, and retail/customer-facing operations.

AD: Between Amazon’s news about testing drones, Fed Ex’s recent announcement about starting to charge by package size, and all of the stories about how many purchases were received late last holiday season, it seems like home delivery has garnered a lot more headlines lately.

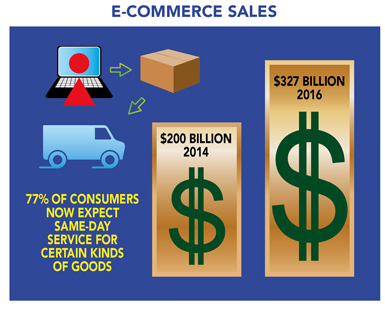

O’Shea: And that’s probably just the tip of the iceberg, because the types of purchases that require last-mile home delivery are on the rise. According to Forrester Research, annual U.S. e-commerce sales are well over the $200 billion mark already, and they’re expected to increase another 45 percent (to almost $327 billion) by 2016. Plus, the value of large product last-mile delivery is now estimated at $12 billion. And that doesn’t even begin to factor in the powerful value of catalogue and direct response sales.

AD:That’s a significant difference. Have companies’ delivery solutions truly gotten that much better over time?

O’Shea: In some cases, yes. For example, there are now some national companies like ours that specialize in providing timely and reliable last-mile service for certain kinds of products. Shipping information systems have experienced huge advances. And companies like Amazon are constantly adding to their networks and capabilities. However, those levels of speed are still not across-the-board kinds of things. In fact, most companies admit that trying to keep up with the omni-channel explosion is a huge challenge for their business. But they know it’s a challenge they can’t ignore.

AD: Why have consumers come to expect such high levels of service if companies aren’t really capable of providing it yet?

O’Shea: Part of it’s driven by mobile connectivity. People have become so accustomed to being able to use their phones to do things at the click of a button — including comparing prices, checking to see if a particular product is in stock, and placing an order — that it’s becoming increasingly difficult for them to wrap their minds around the fact that products can’t move at the same lightning speed. If they can see it on the screen or at the store, they can’t fathom why it can’t be at their homes almost immediately.

Also, a lot of it is being inspired by companies that are using delivery speed as a competitive differentiator. When companies like eBay and Google show that they can successfully deliver within hugely ambitious delivery windows — even if it’s only in select markets or for certain products — it prompts consumers to question why other companies can’t do the same. Ultimately it makes those new levels the “new normal” that every business has to aim for if it wants to stay in the game.

AD: How tolerant are consumers when businesses CAN’T keep up with these faster order-to-delivery speeds?

O’Shea: In today’s highly competitive business arena, there’s not a lot of room for failure — either in terms of shipping speed, product availability, or order accuracy. According to a 2013 survey conducted by Pitney Bowes, 47 percent of consumers pay more attention to shipping as part of the overall shopping experience than they did even a few years ago. Another study suggested that 40 percent of e-commerce consumers have abandoned their online shopping carts when they’ve realized a delivery time would be too slow. Adding to that, 29 percent of respondents to a study conducted by Voxware said they’d take both their e-commerce and brick-and-mortar business somewhere else if they received even one incorrect delivery from a company. Plus, we all saw last holiday season how a small percentage of late deliveries — 3 to 4 percent by some estimates — made it seem like more items were delivered late than delivered on time, and how that impacted some carriers’ and retailers’ brand reputations for the worse.

AD:Those are some pretty high stakes! So what does this mean from a logistics site selection perspective?

O’Shea: If you’re a national company that wants to stay competitive, then having a good supply of shippable “local” inventory on hand — or inventory that’s very close to being local — is going to be a must, because it’s the only way you’re going to be able to keep pace with customer expectations as they evolve.

AD: Sounds like a tall order. Will companies have to operate more warehouses or fulfillment centers — or change the mix of cities in which their distribution centers are located — in order to achieve it?

O’Shea: In some cases, yes, especially if they have highly centralized distribution footprints and a widely dispersed customer base — or if their current facilities don’t have enough room to allow for the kinds of labor-intensive picking and packing areas that will be required. Plus, companies may begin to place more value on having some DCs that are close to major parcel carriers’ hubs so that they can extend their daily cut-off times for customer orders. Look for this to happen in markets like Memphis, Louisville, Philadelphia, and Indianapolis.

AD: Besides proximity to consumers, are there any differences in terms of what a highly efficient omni-channel–era warehouse looks like versus its traditional counterpart?

O’Shea: Consumer fulfillment operations are more labor-intensive, which means they’ll generally have more employees or temps working in them than a traditional DC. As a result, companies will need to more strongly consider how much access they’ll have to a highly qualified labor pool — and ample parking — when comparing sites. In addition, the HVAC, fire protection, disaster recovery, and other safety requirements will be more intense.

Clear ceiling heights of 36 to 40 feet are also highly recommended, because whether companies combine their traditional and fulfillment space under one roof or operate a stand-alone fulfillment center, using mezzanines can help stratify the various activities that are required. It will also be imperative to thoroughly check out the typical zone-to-zone charges and average delivery times for their carriers of choice from each potential site, because even small differences can really add up.

AD: All of these recommendations are well and good. But many companies may not be in a position to add to or modify their DC footprint quite as rapidly as the consumer marketplace seems to be changing.

O’Shea: There are plenty of other options. For example, companies can use their suppliers to ship single orders directly to their customers instead of to their stores or distribution centers.

AD: Which is why even manufacturers or suppliers that don’t sell directly to customers may find themselves involved in the omni-channel arena?

O’Shea: Exactly right. Plus companies can always take advantage of third-party logistics providers’ locations, because those locations are often situated in the most populous consumer markets. But it’s also important to note that most companies already have a lot of shippable local inventory in place that can be used for fulfillment purposes, even if they don’t think of that inventory in those terms.

AD: Can you explain that?

O’Shea: That’s the product situated in their brick-and-mortar sales operations. Unless companies are lucky enough to be able to operate dozens of warehouses near almost every consumer they sell to, their local stores or offices are going to be their best chance at fulfilling most same-day or next-day orders — whether it’s via outbound delivery or customer pick-up.

AD: Give us an example of how this works.

O’Shea: Let’s say that we’re a business that has sold new appliances to a newly built, 10-unit condominium complex in St. Petersburg, Florida. The builder purchased the appliances through our online commercial sales center, and they’ll ship directly from the manufacturer to the complex, with arrival scheduled for October 10. Many of the new owners of the pre-sold units are scheduled to close on their condominiums and move in the following day.

Unfortunately, when the delivery arrives, it turns out one of the built-in wall ovens was damaged and can’t be installed. If our company’s only option is to ship a replacement from our nearest distribution center in Dallas, it would result in a delay of at least a couple of days, meaning someone’s closing would have to be pushed back, the builder would incur extra carrying costs, and the owner would be justifiably angry. Plus our company might lose the builder’s future business because of the issue. But, thankfully, our business has a retail store in Tampa that has the same oven in stock. We immediately notify the store to pull that oven, arrange for an immediate pick-up, and get it to the complex in time for it to be installed later that day. Everything from the client relationship to the new owner’s peace of mind has been saved. That’s the essence of omni-channel efficiency.

AD: It sounds good in theory. But are most companies’ retail or office locations adequately designed to pull off this kind of hoop-jumping?

O’Shea: It may require some reconfiguration or expansion of companies’ retail or customer-facing office space. Among other things, they’ll probably have to expand their stores’ back rooms to accommodate order staging and packaging. And they’ll either have to train their store sales personnel to provide order fulfillment or hire fulfillment personnel to take care of it. Plus, companies may have to invest in more robust warehouse management systems or order management systems — and additional licenses. But it’s definitely achievable. In fact, many companies are already doing this to some degree.

AD: So if a company isn’t already thinking of how to use all of its operations to help enable or provide better delivery service…

O’Shea: Then there’s no time like the present to get started — because the chances are good that there are several competitors who already have a game plan. The omni-channel isn’t a fad or flavor of the month. It’s the shape of the future.