Rural America’s perceived demise needs some context.

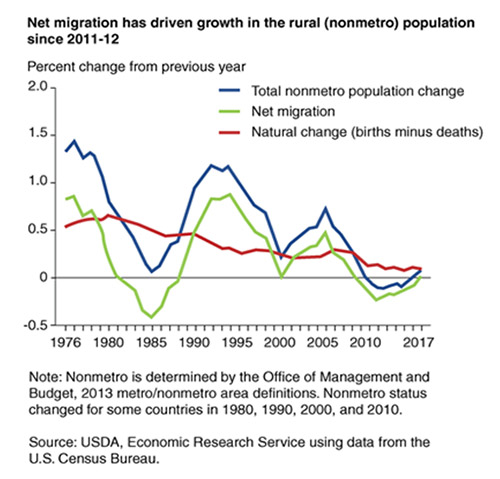

The Economic Research Service (ERS) of the United States Agriculture Department provides periodic analysis of rural population trends. And like so many labor and economic issues, it’s a mixed bag. There is no denying that rural areas as a whole have seen their growth rate fall since the early 90s. And, long before then, the industrialization of agriculture began the process of pushing away scores of family farms.

But until this last decade, while the growth rate was falling, nonmetro counties were still seeing population growth. The first ever population decline occurred from 2010–2016, but 2016–2018 saw that trend reverse. Put another way, rural population growth has been slowing, not declining.

Additionally, rural migration fluctuates with the economy. Nonmetro net migration fell sharply during the Great Recession, as it did during the economic recession of the early 1980s. As the economy gained steam in the 2010s, total nonmetro population has begun to rise again. Of course, with the coronavirus pandemic and subsequent economic crisis, the question of how rural communities will weather the storm is top of mind.

The trend, which hasn’t adjusted with the market, is natural change — births minus deaths. Growth in this area is expected to continue its decline. As a result, migration and its influence by the economy will become the primary driver of population growth in rural areas. But it’s probably worth noting that many people want to live in less populated areas.

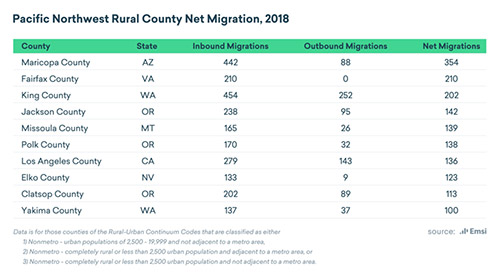

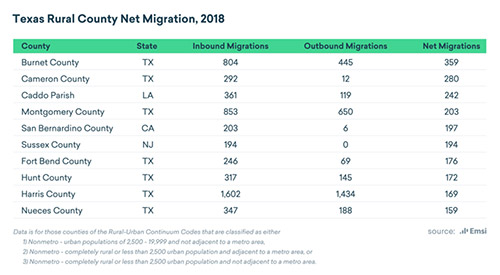

Just like cities, rural areas and communities are all different — and so are their migration trends. The ERS points out that northern Appalachian and southern Coastal Plains continue to experience out-migration, while the Pacific Northwest, Upper Great Lakes, and Florida have switched from net out- to in-migration. Meanwhile, the southern Appalachians, the Ozarks, and the Hill Country of central Texas are seeing in-migration grow.

So, some communities are doing well, some are turning things around, some still have an uphill battle ahead of them. And this points to perhaps the biggest problem with our approach to rural economies: we lump all rural places into the singular “rural America” bucket. Even the defining of rural does this in some ways. The Census Bureau defines “rural” simply as any areas that aren’t metro. Fortunately, however, when analyzing rural data, more specificity is often used. The Office of Management and Budget uses six nonmetro categories based on degree of urbanization and adjacency to a metro area.

As an example of rural differences, we could look at where net in-migration is coming from in the Pacific Northwest versus Texas. Considering the Pacific Northwest to be Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, of the top-10 locations movers, the majority moving to rural Pacific Northwest came from outside the region, with the top two counties being Maricopa, Ariz., and Fairfax, Va. Whereas rural Texas saw the majority of its top-10 net migration in 2018 from within the region.

There is no denying that at the macro level, places outside metropolitan areas are losing people and opportunities. But as long as the uniqueness of each rural community, even regions, is ignored, any attempts to resuscitate them will fail. Rural communities shouldn’t be addressed as a monolith. Just as urbanists focus on the distinct needs and opportunities of each neighborhood, policymakers and economic development professionals should do the same in rural communities.

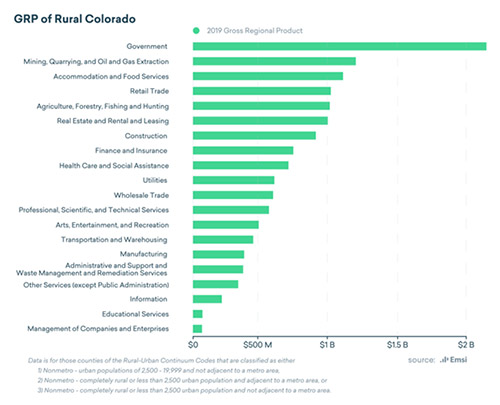

Population trends of rural areas are often all lumped together, as are their economies. Perhaps the most common perception of rural areas is that they are all crop fields. But rural economies are driven by industries as diverse as their landscapes: recreation, oil and gas, manufacturing, crop production, and others.

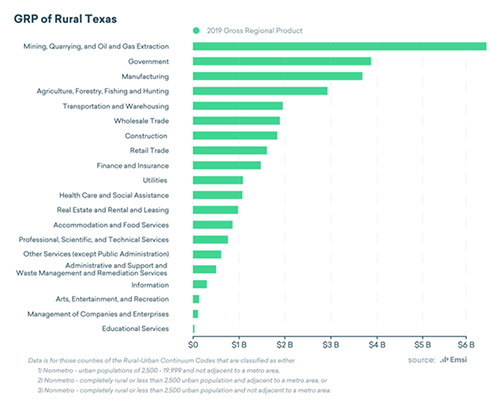

Take Texas and Colorado, for example. While there are some similarities — chiefly the role of mining and extraction — their rural economies are much different. With recreation a staple of the Colorado economy, accommodation, food services, and retail make up a larger portion of their economy in Colorado than in Texas. Conversely, manufacturing is a major component of Texas’ economy, but a relatively small part of Colorado’s.

Although they differ in industry mix, making them each unique, rural communities do indeed have some similarities. One is their susceptibility to booms and busts. In producing our Talent Attraction Scorecard, this is something which becomes apparent year after year. Quite often a small county will skyrocket in the rankings with the discovery of an oil shale or the opening of a single production facility. A federal policy shift can have the same effect. In our 2020 rankings, Hudspeth County in Texas, which is on the U.S.-Mexico border, jumped into the top-five for small counties. Population growth and a rise in educational attainment of residents is presumably due to an increase in border patrol and immigration service employees since 2016.

Another commonality is that while not all rural areas are crop fields, those that are have nearly universally struggled with the consequences of agriculture being industrialized. The shrinking number of small family farms is something with which communities and families continue to grapple. A seemingly final shift away from an agrarian economy is a bust that has been occurring for decades now.

Assessing the health risk due to COVID-19 of more densely populated areas, companies are taking a longer look at rural areas. As businesses make this consideration, there is a great opportunity to better partner with those communities as opposed to simply investing in them. Bluntly speaking, there is an opportunity to reverse the trends of economic colonialism.

Just as the success of a local neighborhood is key to the success of a city as a whole, the success of rural communities is vital to the success of states and regions. We often forget, but all economic development is local. The common saying “all politics is local” should perhaps be commandeered by economic developers. The whole idea is the betterment of local communities. When a bit more focus is placed on the context and uniqueness of rural communities, perhaps they will find more success, which will undoubtedly benefit those of us in cities.