Protectionism or Globalization?

There is some irony that after his inauguration President Trump’s first meeting with a foreign leader was with UK Prime Minister Theresa May. While the President had spoken of “America First” in his speech, the PM talked of a “truly global Britain” just three days earlier. So while the notion of “bringing jobs back to America” is nothing new, it was the President’s campaign and ongoing tweets, particularly in relationship to Mexico and China, that have amplified the discussion. Will there really be a tax on companies investing in those countries, which then export back to the U.S.? Notwithstanding the complications of supply chains in making such a policy practicable, it’s difficult to imagine implementing such a policy that applies to those two countries, while striking up a bilateral deal with the UK that removes similar impediments. Ultimately though, we simply don’t know how U.S. policy is going to look, as there is currently no detail beyond the headlines.

At least in the UK, much is made of the “special relationship” with the United States. While often cast mainly in political terms, the economic angle is arguably more important, and will become more so, as a “hard” Brexit appears to loom. This outcome could mean tariffs and other barriers for UK trade with the EU, such that a deal with the U.S. gains greater significance.

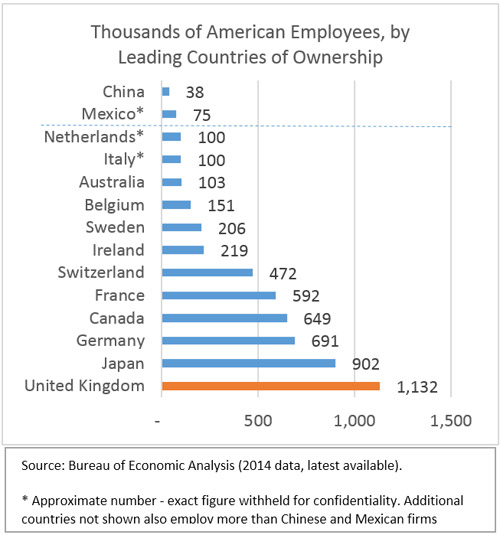

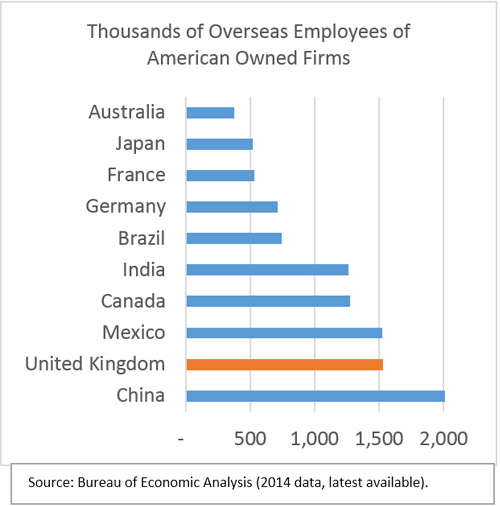

The UK is already the largest investor in the United States — more than one million Americans are employed by British-owned firms. In contrast, Chinese firms employ just 38,000 Americans (3 percent of the UK figure). At the same time, the U.S. is the largest outward investor in many countries, including in the UK, employing more than 1.5 million people there. This is the key challenge for the UK: given the relative sizes of the two countries (demographically, economically, and politically), the UK needs the U.S. more than the U.S. needs the UK. So any trade and investment deal may well be favorable to U.S. firms. At the same time, the UK is conscious of being careful in its approach to an unpredictable U.S. administration.

Invest in the UK or the EU?

So what decision should a U.S. firm make for its first greenfield venture to Europe? Of course, every site selection choice should be based on the unique circumstances of that firm, following the usual process of cost and quality factors. But where it’s now become an explicit choice between the UK and the European Union (itself with three million employed by U.S. firms), is your firm willing to wait at least two years for more clarity on Brexit, and its consequences for UK-based entry into the EU market? Equally, are you also willing to wait for clarity on the United States’ own trade policy?

If waiting is not an option, an investing firm needs to think about the following:

- Are you looking to invest specifically in the UK, or as a bridge to the 27 other countries of the EU as well?

- If the latter, then what is important to your firm? If its culture and language, then Ireland becomes a strong candidate. But then transporting goods to the mainland is more of a challenge.

- In what sector is your firm? There has been discussion that the UK may gain easier access to the EU market in certain sectors.

- Do you believe a bilateral U.S.-UK agreement will open up major opportunities, which outweigh ease of EU access? For example, there has been suggestion that a deal could allow U.S. corporate access to the UK public healthcare system, or that food standards would be reduced to the benefit of investors.

- If exporting from the UK to EU is important, then do you believe a weaker UK currency could offset the costs of tariffs and sourcing goods from the EU supply chain?

- Does the prospect of greater incentives in the UK make a difference to you (given that EU incentives are regulated)? Likewise, are the likelihood of a UK reduction in regulation and the ability of the country to set all its own policies convincing arguments to choose the UK?

- Would access to a skilled UK workforce be compromised by the implementation of stricter immigration laws after Brexit?

There’s a difficult balance where the federal attraction body, Select USA, continues to work to bring investment to the U.S., while reciprocal investment overseas appears to be discouraged. Nevertheless, could Brexit mean that rather than investing in each other, both UK- and EU-based firms now look more to the U.S. instead? At the same time, do reservations about investing in the U.S. given the policy uncertainty offset this possibility? Either way, U.S. economic development organizations need to monitor and react to this changing opportunity, both in terms of exports and investment.

Predicting the Future

Economists are always trying to predict the future. But it’s guesswork to estimate the investment and export environment that will face both U.S. and UK firms two years from now. There are simply too many unknowns: Will the U.S. administration adapt the types of trade policies it has hinted at, or will pragmatism — or the distractions of other events — eventually see little tangible change? Will the UK government get the Brexit deal it wants, or not get a deal at all? Even if it does get the “right” deal, beyond a few broad themes, what does that really mean? Only time will tell.