The manner in which a commercial real estate executive approaches a headquarters decision depends on the specific needs of the company, but general keys to success include seeking input upfront from stakeholders (HR, finance, operations, management, etc.) to create a repository of relevant information, as well as a sense of ownership in the decision process; identifying the issues that matter most to the organization and focusing the team’s energy and resources on these concerns; applying quantitative techniques wherever possible, which helps diffuse political agendas, while expediting and simplifying the decision process; and documenting the process in a strong business case that supports the recommended real estate solution.

In many cases, real estate decision variables can play a role in supporting and strengthening competitive advantage

A Long-Term Decision

Since it is not unusual for a company to occupy a headquarters facility for 10 years or more, a variety of considerations need to be addressed:

- What is the optimal location?

- What are the space requirements near- and long-term?

- What level of quality and amenities match the image the company wants its headquarters to convey to employees, clients, and shareholders?

- What is the likely occupancy duration and what degree of flexibility is needed for extension, expansion, contraction, or termination?

- What type of work environment will maximize productivity and effectiveness?

- And last but not least, what transaction structure makes the most sense, and what will be its financial impact?

A fundamental first step is awareness of how the company competes in the marketplace. Does it compete on cost, service, innovation, speed-to-market, or some other competitive advantage? In many cases, the real estate decision variables described above can play a role in supporting and strengthening this competitive advantage.

How Much Space Do We Need?

Commonly asked by stakeholders at the outset of a headquarters decision process, the chief financial officer, who is charged with financial stewardship of the firm’s resources, and the chief operations officer, who is charged with execution, may have very different answers to this question. So how does the company’s commercial real estate team offer an objective, analytical approach to help all stakeholders agree on size and level of flexibility for future growth or contraction? One way is to model growth by using historical growth data and year-over-year volatility to determine expected future growth, along with high and low estimates. This approach helps size the facility for the “most likely” or “average” growth scenario and enhances understanding of potential future expansion and contraction needs.

Other techniques that can be effective are using company revenue projections or broader economic projections (such as the growth rate of the subject industry) as starting points for forecast development. For companies in acquisition mode, it is helpful to develop scenarios that incorporate potential future acquisitions based on an understanding of how acquisitions are integrated and how they impact space needs. It also is important to consider shifts in the way the organization’s workplace will evolve in the future, as many companies are shifting to denser and more agile workplace environments, which can decrease overall space requirements.

Selecting a Location

Location preferences can be rooted in a number of business issues, but the most common are access to employees; access to customers, suppliers, or partners; and a desire to take advantage of cost differences between regions.

One tradeoff that companies commonly consider is the willingness to accept a higher cost structure in order to locate near a highly skilled workforce. An example of this tradeoff can be found in the experience of one leading Bay Area software developer, which is always seeking to hire the brightest programmers and most creative designers to compete successfully within its niche. As the company analyzed the implications of a move to Sacramento, California, it realized that it could save $8.00 per square foot annually on occupancy costs (22 percent savings) and $13,000 per employee annually in labor costs (16 percent savings). While a move to Sacramento could lower the company’s cost structure and boost earnings, it might also undercut the company’s competitive advantage and destroy its position as a market leader. After sizing up the potential cost savings associated with such a move, the company dismissed this option.

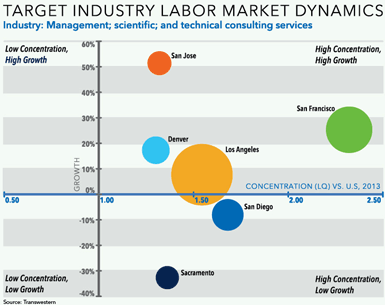

By contrast, a city-by-city industry cluster analysis is used when comparing alternative locations in cases where industry-specific skill sets are required to support the operation. In these cases, analysis of industry size, concentration, and growth patterns are critical to success. Examples include pharmaceutical research and development personnel, software engineers, and experienced insurance underwriters.

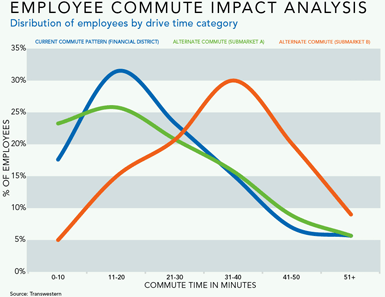

An existing employee demographics map shows where the existing workforce lives, giving the team a sense of which locations will minimize commute-related impacts and attrition. A commute disruption analysis takes employee demographics a bit further, providing a quantitative look at specific locations that are pre-determined by the team.

When a headquarters facility contains different functions and management has no desire to split functions into separate facilities, companies may be forced to make informed tradeoffs during the location process. Consider the case of an international textiles company seeking its first U.S. site. In addition to using the location as its U.S. headquarters, the facility would also function as a manufacturing and distribution center. As might be expected, the location criteria were very different for the headquarters versus the manufacturing/distribution components of the operation.

The manufacturing/distribution component of the decision was driven by the cost of manufacturing (labor, utilities, etc.) and distribution (inbound and outbound transportation) for raw materials and finished goods. Also at issue were the availability of water resources for the manufacturing process and access to a textiles-oriented labor force. The lowest-cost location was identified using a network optimization model, a mathematical tool that identifies the location with the optimal cost structure based on transportation costs, production costs, customer service levels, and other variables. Locations that performed well from a cost and customer service standpoint were then screened for labor supply and water availability.

The headquarters component of the decision was driven by a desire to focus on business development. The company wanted to use the headquarters facility to showcase its technology and products so it needed to be easily accessible for existing and future customers. The optimal location for access to customers was identified with a mathematical model that weighted all current and potential future customers based on order volume. The model used actual order history for current customers and a management list of targeted future customers and their anticipated future order volume. In addition to analyzing weighted distance from key customers and prospects, airport accessibility from specific major cities was included as part of the decision criteria.

One tradeoff that companies commonly consider is the willingness to accept a higher cost structure in order to locate near a highly skilled workforce

In this case, the optimal location from a business development and customer relationship standpoint was in the Northeast, while the optimal location from a manufacturing/distribution standpoint was in the Southeast region. Ultimately, management had to weigh the tradeoff of producing a lower-cost product in the Southeast versus producing a higher-cost product closer to customers in the Northeast. The company chose the former and dealt with the customer access issue by locating near a major city with an international airport.

Economics: The Common Thread

Economics play a leading role in most headquarters location decisions; therefore, it is critical to prioritize the financial drivers that will impact decision-making. Is minimizing the cash net present value (NPV) the primary financial objective? Or is minimizing profit and loss impact more important? Is the company interested in capital conservation to the point that it would accept a higher recurring rent structure in order to avoid a near-term capital outlay? Are there financial constraints that must be honored for the company to stay in compliance with existing debt covenants? Understanding the answers to these questions enables the team to tailor the analysis to the specific information needed by company management.

If a company is considering multiple states or regions for its headquarters location, it makes sense to start with a regional location analysis, which compares the major costs of doing business in one region versus another. This analysis will employ average lease or purchase rates as a basis for modeling occupancy costs (rather than specific real estate opportunities) and will include all of the location-specific costs that impact the company’s cost structure, offset by economic incentives negotiated with state and local authorities. After the alternate locations are narrowed, the model is refined to incorporate the economics of specific real estate opportunities and refined further as the company, owner/seller, and economic development authorities exchange proposals and counterproposals. One important point to recognize is that economic incentives do not make a bad location good. It makes the most sense to first identify locations that will support sustainable competitive advantage and then engage more deeply with authorities on negotiation of economic development incentives.

Economics play a leading role in most headquarters location decisions; therefore, it is critical to prioritize the financial drivers that will impact decision-making

Once location finalists are identified, the real estate process begins in earnest. Depending on the company’s financial objectives and desire for flexibility, its needs may be better aligned with one type of transaction over another, and a lease-versus-own analysis should be explored. This has become especially important in light of imminent changes to lease accounting rules. Ensuring the commercial real estate team has the multifaceted skill set necessary to address this final factor in the headquarters location decision can drive measurable value for an organization.

A well-planned and executed headquarters location decision process has many facets. If the process is framed properly and includes the appropriate stakeholders, and if political agendas can be set aside in favor of an analytical approach, headquarters decisions can be additive to the company’s top-line growth and help executives manage cost structure and risk.