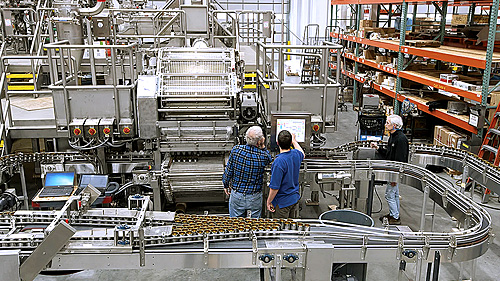

Whether it’s building a food and beverage plant or operating one, three major disruptions persist: supply chain challenges, labor shortages, and e-commerce, which has seen explosive growth during the pandemic as consumers looked for new ways to shop. What they all have in common is they are forcing food and beverage processors to reimagine what their processes look like, how they will carry out those processes, and even the facilities they will use to make their products.

Supply Chain Challenges

In many industries, the answer to supply chain challenges is a relatively simple one: Look to a new provider or stockpile the materials you need to guard against future shortages.

But it’s not that simple for food and beverage processors. Ingredients have a shelf life, so you can’t just stock up on extra perishable items because you expect them to be in short supply in the future. Producers of livestock and crops cannot ramp up production the way a supplier of cardboard boxes can. And many ingredients only come from one region, so disruptions in that region — whether COVID outbreaks, natural disasters, or any other disruption — can force processors to scramble to meet their needs. Many ingredients are shipped to arrive just in time for production, but disruptions to the supply chain have interfered with that timing, as well as making it harder to find new supplies on short notice.

Ingredients have a shelf life, so you can’t just stock up on extra perishable items because you expect them to be in short supply in the future. “The expectation has changed. Our food and beverage customers continue to grow. In response, we continue to innovate with engineering, design, construction, automation and controls, and equipment manufacturing techniques that allow us to be more efficient,” says Tyler Cundiff, president, Food & Beverage Group, Gray, Inc. “This hasn’t happened just as a result of COVID, but it’s been happening for the past several years. We’ve been moving our subcontractors and our own construction professionals to work more closely with material suppliers and design technologies to have greater ability to pre-fabricate various builds for part of the facility, part of the equipment, or infrastructure for the equipment.”

Food and beverage processors face another supply chain challenge on the construction and renovation side. Delays and cost spikes in materials lead to longer lead times and more expensive building materials, replacement parts, and new machines. A project that may have been measured in weeks before the pandemic can now take months, and larger projects face can face even longer delays.

Building a single piece of process equipment involves hundreds of steps, and many of them are in sequence. A delay at one point in the process doesn’t mean fabricators can just move on to a different part of the process and come back later. It stops the process entirely until the needed parts are in hand. The disruptions of the pandemic era have been felt throughout the manufacturing process, says Perry Henderson, vice president, Marketing and Business Development, Anderson Dahlen Inc., a Gray company.

“It was a disruption of manufacturing businesses, including material-producing businesses; with mining and processing of things you need to make components and electronics,” says Henderson. “Almost every piece of processing equipment was directly impacted by not being able to get certain electronics for the controls, and not being able to get certain components for pumps, valves, and other ancillary parts.”

Labor Shortages

Materials shortages have forced food and beverage processors and their suppliers to adapt. But even when they have materials in hand, they need people to operate production lines, build and maintain equipment, and undertake construction projects. Skilled labor was in short supply even before the pandemic hit, and it has only gotten worse since then.

Skilled labor was in short supply even before the pandemic hit, and it has only gotten worse since then. Consider the process of building a new food plant. An engineering or design-build firm works with the customer to design and engineer the building, then hires contractors to build it. Those contractors often hire subcontractors for specializations such as plumbing, electrical, or HVAC. The firms have existing relationships with a number of high-quality contractors, who in turn have a stable of subcontractors they can rely on.

But if a subcontractor has three plumbers assigned to a project and they are all out of work for a couple weeks because of a COVID outbreak, it can slow down the entire building project. And it’s not as easy as simply hiring new plumbers, because subcontractors need to be vetted to ensure they are performing work that is up to the necessary standard.

There’s another issue as well. That plumbing subcontractor may already be committed to another project, because after an initial slowdown due to shutdowns or engineering firms and tradespeople working through how to safely do their jobs, construction has continued at a breakneck pace. Skilled tradespeople have no shortage of work, so there’s no guarantee that a firm or a contractor will be able to get their usual subcontractors, which means new subcontractors have to be evaluated and hired to get the work done.

One other challenge: If everybody’s looking for employees, they might try to hire yours away.

“Your manufacturing infrastructure is one thing,” says Cundiff. “The labor and what everybody’s calling the Great Resignation — that’s impacted manufacturing jobs as well. So, maintaining a high level of retention, whether it’s with our engineering teams or manufacturing teams, is a constant challenge, and it just brings to light the focus on people and culture.”

From the equipment side, finding enough people — and keeping them safe — forced manufacturers to rethink their entire process, says Henderson.

Managing material and worker movement throughout a building has long been a staple of food and beverage due to allergen control and managing cross-contamination. “Acute labor shortages popped up a lot because of people being out, or needing to be isolated, or having to change work patterns to not have people come into contact as much with each other,” says Henderson. “This affected all types of operations, but it affected equipment manufacturing as well. You had to rethink your workflows and how you manage your movement of materials back and forth within the building, or even receiving it into the building. And that’s everything from inspection, to parts movement, to handoff between departments, or project managers going to check on things in production.”

But the disruptions have also provided a learning opportunity for Anderson Dahlen, and one of the takeaways has been adapting to operate more like a food and beverage plant. Managing material and worker movement throughout a building has long been a staple of food and beverage due to allergen control and managing cross-contamination. What Henderson learned is that those trusted principles can also work in an equipment manufacturing environment. The company realized its team members were spending a lot of time moving from one place to another within the building, and they didn’t necessarily need to be doing so. For example, if fabrication had a question for engineering, then a common solution was for someone to walk over to engineering, explain the issue at hand, then walk back to the piece of equipment in question with the engineer accompanying them. The company realized that by modifying the way people and materials moved both throughout the building and the fabrication process, it could eliminate much of the unnecessary movement throughout the building.

“We actually kept it that way because it gained efficiency in the end,” says Henderson.

E-commerce places different demands on a food and beverage plant than retail and food service do, so flexibility is paramount. Whether it’s processing lines, packaging equipment, or shipping, processors who have seen significant growth in e-commerce businesshave had to adapt their operations to meet that demand. People may be returning to the grocery store, but that doesn’t mean they’ve stopped ordering certain things online.

E-commerce is also offering opportunities for startup companies that make products such as meal kits or other items sold directly to consumers. E-commerce is also offering opportunities for startup companies that make products such as meal kits or other items sold directly to consumers. Not shipping to grocery stores or wholesalers creates a need for a different kind of food plant, as well as different demands for processing and packaging equipment.

But for processors who already have retail or food service customers in addition to e-commerce, it’s more about adapting current equipment and processes to meet the needs of each market. Equipment manufacturers are adapting to offer more flexibility in equipment, and engineering firms are rethinking the design of packaging lines and other aspects of the production process to ensure they are able to change over with minimal time lost.

And, of course, supply chain challenges and labor shortages play into the e-commerce side as well, because just like any other food product, materials and people are needed to produce the products.

All these challenges tie into each other, and they all create disruptions. As Cundiff says, there’s no set answer to solving any of them, but the industry is tackling them head-on and it is continuing to focus on future growth. “In spite of all these challenges, we continue to see food and beverage companies wanting to heavily invest in larger, more modern processing facilities,” he says. “We’ve never seen the demand like it is now, and there’s no indication that it’s going to slow down.”