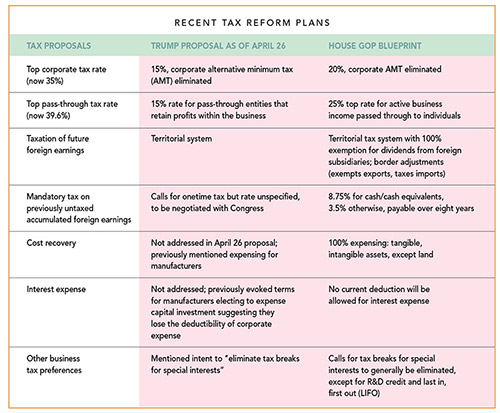

The current tax reform plans outlined by President Trump on April 26, 2017 and the House GOP Blueprint (see accompanying table) go about promoting growth through a number of commonalities: reducing individual and corporate income tax rates, general elimination of tax breaks for special interests, etc. These plans effectively create a broader federal corporate income tax base while reducing the corporate income tax rate.

On July 27, 2017, the “Big Six” (a group of administration and congressional negotiators) announced that they had set aside border adjustability in order to advance a tax reform that “reduces tax rates as much as possible, allows ‘unprecedented’ capital expensing, places a priority on permanence, and encourages U.S. companies to bring back jobs and profits from overseas.” The result of U.S. tax reform may also impact the direction of future trade proposals currently being evaluated by President Trump. On February 28, 2017, while speaking to a joint session of Congress, President Trump stated, “We must create a level playing field for American companies and workers. I believe strongly in free trade but it also has to be fair trade.” He repeatedly stated his intention to renegotiate or withdraw from the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) during his campaign, and a short time later, on May 18, became the first American president to begin renegotiating a comprehensive free trade agreement.

NAFTA trade rules have led to integrated supply chains among companies in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico for the past 23 years. Companies with strong international activities such as these will want to monitor both trade and tax proposals and consider the potential impacts on their businesses.

When discussing the impact that federal tax reform will have on state taxes, it is important to consider both the income tax base (the amount of income that is subject to tax) and the income tax rate that is applied to the base. The general principle for federal tax reform is to broaden the base and lower the rate.

States use the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) as the starting point for determining state taxable income; therefore, if the IRC changes, for example by deduction, elimination or credit modification, which broaden the federal tax base, barring any additional state tax law changes, these will broaden the state tax base as well.

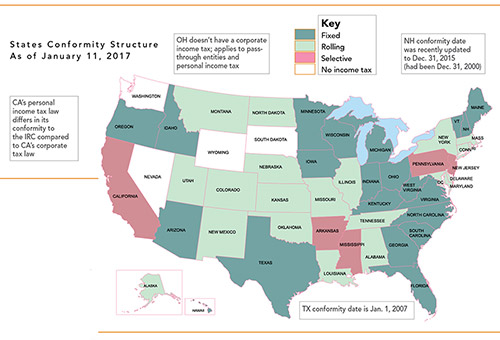

States differ on how they conform to federal changes, following a rolling, fixed or selective conformity structure. The accompanying map illustrates each state’s conformity structure. Sixteen states are either currently undertaking comprehensive studies of their tax system or have recently completed studies with final recommendations; but with federal tax changes potentially being released in 2017 or 2018, it is unlikely that there will be enough information to trigger these states to make dramatic changes to their own structures accordingly.

Regardless of how states handle federal conformity to the IRC, it is important to also look at how they may alter their tax rate. The federal government is expecting tax reform to be somewhat neutral from a budget prospective, despite the lower rate, because the lower rate is expected to be applied to a broader base. While those states that have some level of conformity are likely to see a broader base, they set their own tax rate. State income tax rate increases and decreases remain at the discretion of the state legislature.

When evaluating whether a state will choose to mirror the anticipated federal corporate income tax rate reduction, it is important to consider the state’s fiscal position, its political alignment, and the term limit of the existing governor. For example, as of March 2017, Republicans controlled 32 state legislatures, including those in Florida, Kansas, North Dakota, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming; these six states anticipate a fiscal year 2017 revenue shortfall. Due to the projected revenue shortfall, these states may not follow the federal government in making a proportional tax rate cut in order to fill that revenue shortfall.

Another 10 states — Alaska, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, and Virginia — have legislatures under split-party control but also have a fiscal year 2017 revenue shortfall. These states, as well as states with Democratic-controlled state legislatures, could very well maintain their corporate income tax rates or implement a smaller rate cut in the short term to reap the benefits of the additional income tax revenue and wait to decrease rates, strategically aligning with re-elections.

The anticipated increase in capital investments and jobs through a reshoring of operations by U.S.-based companies, coupled with increased foreign direct investment (FDI), driven by tax and trade reform discussed above provides a fertile landscape for states to compete for the additional spend and jobs. For example, the Texas Taxpayers and Research Association (TTARA) has already begun reaching out to manufacturing companies, reminding them of the ability to benefit from property tax relief under Chapter 313 if certain conditions are met.

In conjunction with state tax reform, state and economic development groups are reevaluating how effective their current tax credit and incentive offerings are and how well they align with the expected impacts of tax reform. With an increase to the state tax base through IRC conformity, and in the absence of a proportional state income tax rate reduction, states could shift revenue to discretionary incentive programs to more competitively vie for these jobs and investments against other states that have discretionary programs.

Although the long-term directive of how states will handle federal tax reform may vary, there is likely to be a short-term surge in state revenue as a result of a broader tax base… It is likely that we will see additional funds allocated toward discretionary incentive programs. Several states have either passed or proposed recent legislation intended to attract manufacturing to their state. For example, th e Wisconsin Economic Development Corporation (WEDC) announced special legislation to pass a $3 billion incentives package to Foxconn Technology Group after the company announced a $10 billion manufacturing facility in Wisconsin. Maryland recently enacted the More Jobs for Marylanders Act of 2017, which provides a variety of tax incentives for up to 10 years for new manufacturing operations. Illinois recently passed House Bill 0162, revamping its jobs tax credit, which includes manufacturing as a targeted industry.

According to the EY 2015 US Investment Monitor, the top five states with the highest capital investment (Alabama, California, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Texas), as well as the top five states with the highest job creation in 2016 (California, Florida, Ohio, Tennessee, and Texas), all have competitive discretionary incentive programs targeted at the manufacturing industry, including California Competes, Florida’s Qualified Target Industry Tax Refund, JobsOhio, and the Texas Enterprise Fund.

Although the long-term directive of how states will handle federal tax reform may vary, there is likely to be a short-term surge in state revenue as a result of a broader tax base. This, combined with the competitiveness between states to capture more than their fair share of any increases in jobs and investments, means it is likely that we will see additional funds allocated toward discretionary incentive programs. At EY, our clients are already benefiting from this as they obtain more attractive and more creative discretionary packages than in the past.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Ernst & Young LLP.