On the employment side, the industry has added over 156,000 jobs since June 2009.1 Productivity in the auto industry is at an all-time high — roughly 40 percent higher than it was in 2000. Automaker and supplier companies are finding new ways to increase production in existing facilities by implementing operational improvements, relying on overtime and three-shift and three-crew operations, and making targeted investments to overcome facility bottlenecks. These improvements have made America a competitive place to make light vehicles and parts. The United States has attracted $29 billion in new automotive investment over the past three years2, and virtually every automaker that sells vehicles here has announced plans to expand in the United States. Today, the auto industry in America:

- Employs nearly 680,000 people3

- Produces over $522 billion in shipments4

- Exports over $128 billion in motor vehicles and parts5

- Supports $564 billion in U.S. automotive sales6

- Supports $173 billion in repairs and service revenue7

- Provides $92 billion in state tax revenues (13 percent of total) in the U.S. (2010)8

- Has a jobs multiplier of 10 — one of the highest of any industry9

- Accounts for 7.7 percent of the private manufacturing R&D expenditures in America10

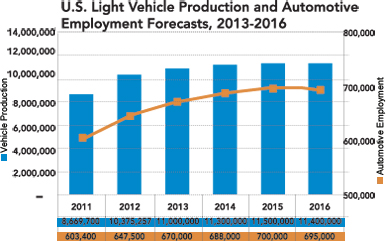

Despite restructurings and benefit cuts caused by the Great Recession, automakers still pay some of the highest wages in manufacturing, and the gap between the Detroit automakers and their European and Asian counterparts has narrowed considerably. GM, Ford, and Chrysler have a mix of lower-cost entry-level new hires and veteran workers, and the companies’ average hourly labor costs (wages + benefits) range from $52 to $60 an hour. Labor costs for the European and Asian automakers range from $40 to $62 an hour.11 While automotive employment is not likely to reach pre-recession levels, there are still substantial employment opportunities. As illustrated in the accompanying chart, the industry will add 30,000 new jobs over the next two years.

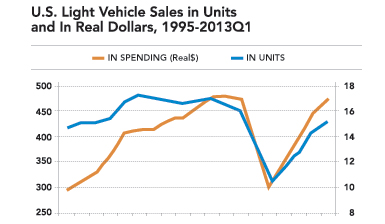

"U.S. Light Vehicle Sales in Units and in Real Dollars, 1995-2013 Q1

Source: Center for Automotive Research

"U.S. Light Vehicle Production and Automotive Employment Forecasts, 2013 - 2016

Source: Center for Automotive Research

Other job opportunities will be created by both the influx of new technologies in the automotive industry, and the expected retirement of tens of thousands of auto workers over the next decade. The industry will be hiring new engineers, technicians, and factory workers — and the skills needed for many of these jobs have changed.

The Skills Gap

Today’s automobile production line requires highly skilled, flexible workers who can rapidly adjust to change. In years past, the primary qualification for working on an assembly line was manual dexterity. Today, companies are looking for people who can work in teams, take initiative, and handle multiple jobs. The stereotype of an unskilled auto assembly line worker, who “checked his (or her) brains at the door,” no longer applies. There is a growing gap between incumbent worker skills and those that will be needed in the future.

The Center for Automotive Research regularly interviews human resource executives at the automakers and major suppliers, and recently asked how the 2008–09 auto industry downturn changed their approach to hiring and retaining workers. Here is a summary of the results:

- There is a greater emphasis on “soft skills.” Production line workers are expected to be problem solvers, with the ability to work in collaborative settings. They must be able to understand the “big picture,” and willing to work for the common success of the enterprise.

- Production workers will be given greater responsibility for continuous improvement and routine maintenance.

- New technologies in powertrain, joining and assembly, and electronics, coupled with faster product cadence, will drive skills changes.

- In skilled trades, we will see fewer classifications, more cross-skilling, and more skill needs in electrical, electronics, and software areas.

Recent surveys of manufacturers show a “skills gap,” with nearly all auto executives concerned about the pipeline of future workers and their ability to work on the modern manufacturing floor. The skills gap is particularly acute among the skilled trades. Newly opened auto plants in the South often have to import skilled tradespeople from the Midwest, and the population of skilled tradespeople in Midwestern plants is rapidly aging.

A recent survey by Deloitte and the Manufacturing Institute found that 74 percent of U.S. manufacturers reported that work force shortages or skill deficiencies in the skilled production work force (machinists, operators, craft workers, distributors, technicians) have had a significant negative impact on their company’s ability to expand operations and improve productivity. Results from that same survey showed that 42 percent of manufacturers face shortages or skill deficiencies in the production support work force (industrial engineers, manufacturing engineers, planners) that have had significant negative impact on their businesses.12

The skills gap doesn’t end with blue-collar workers. For example, Ford Motor recently announced it will add 3,000 white-collar jobs to meet the new high-tech demands in the auto industry. The company has expressed concern about finding enough workers to fill those spots. Most of those new hires will be engineers and IT specialists needed to design the next generation of vehicles — vehicles that are being designed with infotainment systems, electronic controls, and safety systems.

Next: The Role of Human Resources in Site Selection