The Mexican economy experienced an annual rate of growth of 2.5 percent during 2015, which helped keep the unemployment rate low (about 4.2 percent in January 2016). Over the first three months of 2016 the Mexican economy grew at a rate of 2.6 percent. Further, according to A.T. Kearney, GDP growth is expected to average 2.6 percent over the next three years, thanks to an expanding middle class, a robust manufacturing sector, and proximity to the U.S. market. Even with low oil prices, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) expects Mexico’s GDP growth to reach 3 percent in 2017, reflecting the positive impact of new government reforms. The current administration of Enrique Nieto Peña hopes to attract US$150 billion in new FDI over its six-year term with $30 billion of that targeted for 2016

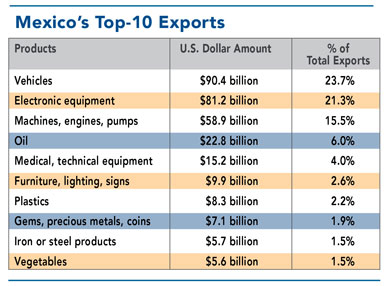

Much of this economic growth is anchored by manufacturing. Exports account for more than 30 percent of the country’s economic output, and overall trade as a percentage of GDP now exceeds 60 percent, outpacing even China. Exports from Mexico totaled US$380.8 billion in 2015, with about 84 percent of these products shipped to North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) partners, the United States and Canada.

In addition to its economic performance, good business climate, and increased trade, Mexico’s new political reforms and improved government stability are making it more attractive to foreign investors, especially manufacturing companies. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Mexico ranks 10th in the world for FDI investment.

FDI inflows in 2015 totaled about US$21.5 billion. The 2016 A.T. Kearney Foreign Direct Investment Confidence Index ranks Mexico 18th in the world, with most of its investors being industrial firms headquartered in the Americas. The Mexican government is committed to increasing foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows in key sectors by breaking up cartels, reducing corruption, and improving competition. The current administration of Enrique Nieto Peña hopes to attract US$150 billion in new FDI over its six-year term, with $30 billion of that targeted for 2016, especially in the automotive, medical device, aerospace, and electronics industries.

Manufacturing-Driven

Manufacturing accounts for about one third of Mexico’s total economic output. Seven of the top-10 exporting groups are manufactured products.

“The benefits that Mexico offers to manufacturers include competitive wages, growth prospects thanks to an open-trade philosophy, reliable infrastructure, proximity to the U.S., an educated workforce, and a growing supplier base,” notes Doug Donahue, vice president of Business Development for Entrada Group, which helps manufacturers locate in Mexico. “These factors combine to make Mexico a location any manufacturer seeking growth has to consider.”

Key Industry Clusters

Automotive: The top manufacturing industry in Mexico is automotive. Mexico became the world’s seventh-largest auto producer in 2015. It now produces more vehicles than Brazil and is projected to be the world’s fifth-largest vehicle producer by 2020. More than three-quarters of the vehicles are exported to the U.S. and Canada. Mexico is also a top supplier of automotive parts to the U.S. As a result, Mexico’s automotive sector has attracted steady foreign investment.

For example, FDI from European and Asian car manufacturers includes recent investments from Nissan and Volkswagen — whose global delivery center in Mexico is the company’s largest production site outside its German headquarters.

Electronics: Electronics is another major manufacturing industry in Mexico, which began with the foreign-owned maquiladoras that developed along the U.S. border decades ago. Electronics manufacturing operations have advanced considerably since then in terms of size, technology, and supply chain sophistication.

Electronics clusters are located close to the manufacturing industries they serve — for example, a northwest cluster supplies parts for nearby automotive and aerospace facilities; to the northeast, electronics manufacturers serve computer and appliance companies. The largest and most sophisticated cluster is in Guadalajara, home to more than 400 manufacturers that employ about 50,000 workers — sometimes called the Silicon Valley of Mexico. Eight of the top 10 contract electronic manufacturers have operations in Guadalajara. In fact, Guadalajara’s high-tech industry — led by electronics — provides 60 percent of the state of Jalisco’s total exports.

Aerospace: Although it is still a relatively small industry, aerospace is emerging as a growth area for high-value production. Mexico’s aerospace industry has grown from 100 manufacturers in 2004 to over 300 in 2016; major U.S. players with operations in Mexico include Gulfstream Aerospace/General Dynamics, General Electric, Textron, and Honeywell. Other nations with an aerospace presence in Mexico include France (Safran Group), Canada (Bombardier Aerospace), the Netherlands (Fokker), and Spain (Aernnova). A significant engine-component cluster is located around Guaymas, in the state of Sonora.

“Boeing and Aeromexico and other key stakeholders are collaborating to move Mexico’s sustainable aviation biofuel industry forward,” says Marc Allen, president of Boeing International. “Sustainable jet fuel will play a critical role in reducing aviation’s carbon emissions and will bring a new and innovative industry to Mexico.”

Oil and gas: Perhaps the greatest political triumph for the Enrique Nieto Peña administration is the reform program that will allow foreign companies to explore for oil in Mexico — the first time this has happened since 1938. This creates open competition with government-owned Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex), which should stimulate considerable foreign investment. However, the current low oil prices have made oil and gas companies reluctant to invest capital until the industry improves.

In 2015, foreign investors did win several bids on exploration lands, including Italian national oil company Eni and several consortia led by oil companies from Argentina, the Netherlands, Canada, and the United States. Oil and gas companies are also highly interested in the potential for shale gas across Mexico. Also, when oil prices turn around and exploration ramps up, significant FDI will likely be spent on pipeline improvements, oil storage, and other refining infrastructure.

Telecommunications: Growth in this sector has been hampered in the past by poor coverage, not enough modern infrastructure, and only a few key players, creating a cartel structure for telecommunications and television broadcasting as well. For example, one company, América Móvil, controlled 70 percent of the mobile phone market and 80 percent of the nation’s fixed lines. Reforms passed in 2014, however, have reduced the influence of these controlling companies, which is attracting foreign companies into this emergent marketplace. For example, U.S. firm AT&T recently acquired two Mexican telecom companies — lusacell for $2.5 billion in November 2014 and Nextel Mexico for $1.9 billion in 2015.

A Promising Future

Reforms to major markets, improved labor laws, and concerted efforts to reduce corruption and crime have accelerated foreign interest in investing in Mexico. In fact, according to Deloitte, “Mexico’s medium-term growth could average 4.5 percent per year, up from a projected 3.1 percent real annual growth rate for 2015-2034, if the government can deliver its broad reform initiatives.” Further, if the Trans-Pacific Partnership is enacted, it could foster even greater foreign investment, “raising Mexico’s longer-term growth rate by close to 1 percentage point.”

Momentum will quickly stall, however, if the Mexican government falters on enforcing reforms and other economic initiatives, including anti-corruption measures. And, with manufacturing creating one third of the country’s GDP, it is important for the government to invest in critical infrastructure, such as transportation and border crossings, to support its growing manufacturing sectors and to attract more FDI. Also, the lack of key infrastructure and adequate water in prime oil-and-gas exploration areas could discourage energy-investing in these territories.

“As Mexico begins to break up longstanding monopolies and push forward with a number of significant reforms, “it will continue to open its economy more fully to global trade and competition,” states Deloitte in conclusion. “There are a number of opportunities that suggest the country’s competitive future should be bright.”