The year 2016 saw not only the election of President Donald J. Trump, but also the Brexit vote in the UK and various nationalist or protectionist movements across Europe. Such changes were momentous from a political point of view, but are also causing companies to find new ways of staying engaged in the global marketplace, even in the face of a protectionist world.

Foreign Direct Investment Trends and Forms

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is the term used to describe investment of domestic companies into other nations or by foreign-owned businesses into the United States. FDI is and has commonly been driven by four major business needs:

- The need to access key resources, such as raw materials and natural resources

- The need to enter new markets to purchase and use the company’s products and services

- The desire to tap into additional assets, particularly talent, key infrastructure, or economic or partner networks

- The need to gain competitive advantage through efficiency gains, cost reduction, or increased productivity

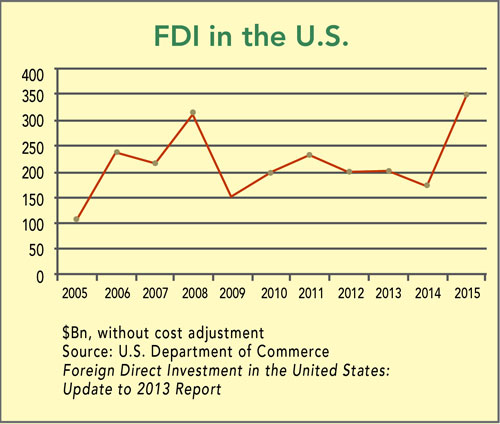

Investment data shows that overall FDI to the U.S. remained relatively stable or even flat until 2015, when it experienced a sharp uptick, resulting in a record $348 billion inflow. The manufacturing (36 percent) and banking, finance, and insurance (20 percent) sectors make up the majority of inward investments. Of course, that data tends to measure direct investment by a company into a new site owned wholly by the company. A further examination of the information shows that beyond the regular continuing FDI trend, alternative forms of investment are becoming increasingly important.

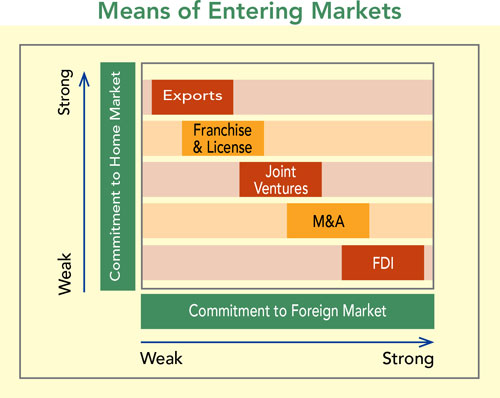

In addition to more conventional direct FDI, companies — both inbound to the U.S. and outbound globally — are exploring vehicles such as joint ventures and M&A as means for entering new foreign markets. In these cases, the companies in question gain existing knowledge of how to operate in the local market, may gain access to pre-existing supplier and customer networks, and enjoy a generally easier path to investment. The drawbacks include some loss of control, lack of integration, and the occasional inability to fully bring their culture, products, and identity to the new market. However, changes in the international scene may put some of this progress at risk.

The Brexit and Trump elections signaled a shift from multilateral trade deals (think the Trans-Pacific Partnership, some aspects of NAFTA, and even some facets of the European Common Market) toward a preference for bilateral deals. Changes to International Trade

Last year was a momentous one for international trade. The Brexit and Trump elections signaled a shift from multilateral trade deals (think the Trans-Pacific Partnership, some aspects of NAFTA, and even some facets of the European Common Market) toward a preference for bilateral deals. In these latter deals, a specific, binding, and reciprocal understanding is gained between two nations. The global marketplace, however, is fractured and complex. Every international interaction requires a thorough examination of yet another treaty.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the UK will formally begin its Article 50 process to leave the European Union, while simultaneously beginning to negotiate a new relationship with the Union. Aside from its relationship with the EU, the UK will also need to re-establish trade treaties with its major trading partners around the world, and many of the same issues of workforce movement and balance of trade will dominate those talks.

In the Western Hemisphere, in addition to discussions of NAFTA, the new U.S. administration has discussed adding a series of border-adjustment taxes in an attempt to address perceived weaknesses in the tax code. In this case, a tax is applied to all goods and services consumed domestically, and specifically excludes those goods and services that were also produced domestically. In this way, the tax is designed to address such issues as tax inversion, movement of production to low-cost offshore locations, and efforts to shelter profits from U.S. tax authorities. At the same time, the administration intends to lower the overall corporate tax rate, and even possibly exclude revenue from export sales from the taxable revenue base. This approach is intended to make domestic production more competitive at home while potentially subsidizing it abroad, but the actual effects will have to be seen in practice. It is also unknown what such a policy will do to currency exchange rates as the market adjusts to the new policies and trade balances.

It is interesting to speculate what the potential changes to the global economic environment might mean for economic development strategies. Direct foreign investment is often preceded by a trade relationship of some kind. If trade deals are to become more fractured and protectionist, FDI might suffer as a result — unless of course there is a means to easily facilitate free trade.

Foreign-trade zones, which were originally a byproduct of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of the 1930, provide a means of retaining elements of a free-trade globalist approach to economic development. However, even with the strengths and benefits of the FTZ program, many of the hundreds of zones across the U.S. remained in dormant status, with few companies using the program for either warehouse or production use. This has been due to lack of information and possibly also to the considerable burden of administration; in some cases, it was also due to the zones not completely covering the territory needed.

While previous legislation allowed for the development of “satellite zones” to cover these outlying areas, the Foreign-Trade Zones Board adopted a FTZ Board staff proposal in 2009 to institute an Alternative Site Framework (ASF) as a means of designating and managing general-purpose FTZ sites through reorganization. The ASF provides FTZ grantees (ports, airports, and EDOs with FTZ administration responsibility) with greater flexibility to meet specific requests for zone status by utilizing the minor boundary-modification process. The theory is that by linking FTZ-designated space to the amount of space activated with Customs and Border Protection, zone users would have better and quicker access to benefits.

The United States — given its heritage as an internationally strong trading nation — has long been both participant in and beneficiary of FDI. When a FTZ grantee evaluates whether or not to expand its FTZ project in order to improve the ease in which the zone may be utilized by existing or prospective companies, the Alternative Site Framework (ASF) should be considered. The ASF may be an appropriate option for certain foreign-trade zone projects, but the decision of whether to adopt the new framework and what the configuration of the sites should be will require careful analysis and planning. Regardless of the choice to expand the FTZ project, the sites should be selected and the application should be drafted in such a manner as to receive swift approval, while maximizing benefit to those that locate in the zone. Successful zone projects are generally the result of a plan developed and implemented by individuals that understand all aspects of the FTZ program.

Even beyond the direct investment aspects of globalization, the role of foreign trade will require some level of adjustment. The Alternative Site Framework for foreign-trade zones may prove to be exactly the right tool at the right time.

The Role of FDI in the Near Future

For the past several years, the U.S. Department of Commerce has held its annual Select USA conference in Washington, D.C., to showcase investment opportunities across the United States and to give regional economic development organizations the chance to mingle with potential investors. This year’s conference provides an interesting window into the investment trends for the near- to medium-term. Will direct FDI slow due to protectionism, or will international companies see a need to establish a footprint and become more “American” in their profile? Will they look to acquire or joint venture with legacy American companies?

Any company looking to directly or indirectly enter the FDI sphere should have an explicit understanding of its goals and its tolerance for risk. Once these are known, the company will have a sound basis for understanding what form of foreign investment will work best to achieve those goals, the parameters to be used to evaluate possible location options, and the knowledge needed to evaluate any incentive program offered to sweeten the deal including the use of foreign-trade zones. Perhaps this tool will find new life in the coming economy.