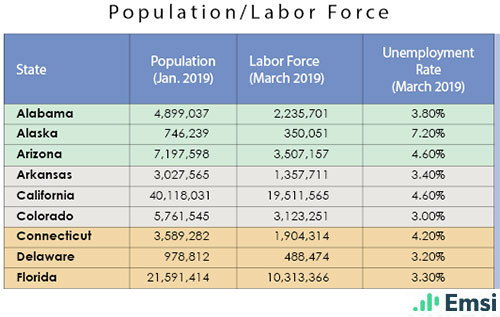

Jobless rates, as calculated by the labor market and economic analytics firm Emsi (see chart), were as low as Vermont’s 2.3 percent in March, and as high as the 7.2 percent recorded in Alaska. All but three states had rates under 5.0 percent, a level that traditionally has been seen as near full employment.

And the picture just kept getting better as 2019 progressed, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, which pegged the national unemployment rate at 3.6 percent by October, two-tenths of a point below what it was a year earlier. The BLS found that nonfarm payroll counts increased by a full two million people over the course of 12 months.

There remains plenty of room to grow that count even further, if employers could have their way and fill all the jobs they’ve posted. According to the BLS, by the end of September there were some seven million job openings, which is actually a quarter million job vacancies lower than a month earlier. Other reports have indicated that the number of people looking for work remains below the total number of job openings, a challenging situation for employers that has been the reality for nearly two years now.

Labor Shortages All Over

The labor issue is widespread across lots of different industries. There’s long been talk about a dearth of qualified applicants in high-skill white-collar pursuits, including science and technology jobs. But these days, according to The Conference Board and others, the problem is often even more acute in lower-wage and blue-collar occupations.

The biggest gaps are in education and health services, as well as in professional and business services. But the more-jobs-than-seekers problem is noteworthy across a wide swath of such industries as mining and logging, durable goods, leisure and hospitality, transportation, and wholesale/retail trade.

Indeed, to take transportation as an example, consider what it pays to be a trucker working for Walmart. The retailer doesn’t exactly have a reputation for high pay, but earlier this year it found the need to offer its truckers a raise, upping the average to more than $87,000. The company also promised more predictable schedules, more paid time off, and the potential for bonuses.

The transportation industry as a whole deals with significant turnover challenges. Researchers report a lot of churn in the industry, and its tendency to rely on older workers makes it susceptible to retirement pressures. The constant uptick in online ordering of everything from furniture to groceries puts an added strain on the labor picture.

Vermont has the lowest jobless rate on Emsi’s list, and the state’s employer community is certainly feeling the pinch. The state is hoping that its new Remote Worker Grant Program will make a difference. The aim is to bring in new residents by offering financial incentives to people who are able to work remotely. Why not do their work from a home base in Vermont, especially if the state picks up the tab for many of their relocation expenses?

Ultimately, Vermont hopes to build its labor force with younger workers. Though new residents lured by the grant program are already employed elsewhere and working remotely, once they put down roots, some may eventually switch to a local job. They also tend to bring family with them when they make the move, building the workforce even more.

A different Vermont approach that state officials tried out last year involved a tourism campaign promoting not only the state’s natural beauty, recreational opportunities and breweries, but also its long-term job opportunities. The campaign offered certain tourists access to events and resources aimed at potential new residents.

The number of people looking for work remains below the total number of job openings, a challenging situation for employers that has been the reality for nearly two years now. Iowa is taking proactive steps to attract new residents as well, as it also deals with an extra-low jobless rate. The state has done a good job of attracting startups and tech companies, but knows that much of the rest of the country still sees Iowa as having a mostly agricultural economy. An online campaign seeks to educate outsiders about Iowa’s lesser-known attributes and solid quality-of-life. There are also ongoing efforts to target younger Iowans about the benefits of sticking close to home once their education is complete. Iowa also has boosted its workforce training initiatives to help fill advanced manufacturing job openings.

Like Iowa, New Hampshire will get a lot of attention in 2020 during the political primary season. And like Iowa, New Hampshire will continue to battle labor shortages in the months ahead. The Granite State has its own efforts under way to educate young residents about local job opportunities and connect them with internships and shadowing opportunities. Its attempts to stem the brain drain, though, are complicated by housing affordability issues.

Meanwhile, Colorado is turning workforce challenges into workforce opportunities. For example, the growing problem of wildfires creates opportunities in fire mitigation, so there are training options for that. Another career program aims to educate Colorado residents for conservation-related careers for dealing with future water shortages. And many Colorado employers are taking their own steps toward opening the doors to more job-seekers. For example, some are loosening drug-testing policies and revising their hiring procedures for applicants with criminal records.

Utah is blessed because a lot of people want to plant permanent roots in the state — the number of housing permits issued last year was the highest in more than a decade. The problem is, who is going to build all that housing? As in many states, there’s a labor shortage in the construction sector. Construction companies in Utah are upping their benefits packages and offering generous raises as they compete for workers, and industry organizations are establishing recruiting initiatives.

Business organizations in Utah also say their state has been negatively impacted by the federal government’s efforts to reduce immigration and refugee resettlement. The Salt Lake Chamber of Commerce, for example, has been pushing for increases in legal immigration, arguing that the economy needs the labor contribution that immigrants have traditionally provided.

In the Hampton Roads region of Virginia, local leaders commissioned a workforce analysis this year to help tackle labor shortages there. The area saw some 30,000 new jobs added over the past five years, but the working-age population increased by just a third of that number. As in so many places, there are lots of working-age people moving toward or into retirement.

That said, the report found ongoing improvements in career training and pathways, and educational attainment above national averages. A variety of programs address the labor shortage, including a Build Virginia initiative offering training in skilled trades and an expanded program aimed at helping military members who are retiring and their families transition into trades-based careers.

One potential solution to the worker shortage: get workers to stop retiring. Officials in North Dakota have been accustomed to filling a large number of job openings, thanks to the oil boom that attracted workers following the last recession. The problem now is there are more opportunities all over the U.S., and fewer people find it necessary to move for work. Job openings in North Dakota are double what they were a decade ago, and some are staying open for months.

It’s not an easy problem to solve, but state officials are doing what they can. For example, a new licensing reciprocity initiative is aimed at military spouses who are in licensed professions and have certifications from other states. The state university system also has new scholarships and loan forgiveness programs aimed at boosting the two-year degrees needed for many of the in-demand jobs.

Changing the Culture

North Dakota’s push for something other than four-year degrees reflects a broader and growing understanding nationwide that America’s higher-education policies of the past are part of the reason for today’s problems. High schools have been judged by college placement, yet a bachelor’s degree isn’t the best fit for some people and isn’t necessary for a lot of in-demand jobs.

At the federal level, there are proposals in the works to beef up benefits and incentives for pursuing technical education. Legislation to that effect has been introduced in Congress, though as of the end of November, it had not yet made it far through the legislative process.

One other potential solution: Get workers to stop retiring. The Bureau of Labor Statistics notes that a number of industries are drawing a disproportionate share of workers 55 or older. Popular possibilities include medical transcriptionists, property managers, bus drivers, travel agents, and museum workers.

Forward-thinking employers are also finding ways to avoid losing their most seasoned and skilled workers. Some, for example, offer reduced work schedules that keep otherwise-retirees on the job for a bit, ready to pass along their knowledge to the next generation. The idea is seen as a way to share and even spark innovation, and it happens to also be good for the financial and mental health of the workers who are putting off their full retirement.