Canada is a developed country and a member of OECD and has become the 11th-largest economy in the world. It is strategically located between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, and its ports are closer to Asia and Europe than the ports serving the lower 48 states of its southern neighbor — the United States, which has the largest economy in the world.

Canada also has a world-class highway system and is home to two Class I railroads. Yet, overall freight movement is highly concentrated along the southern border, as more than 80 percent of Canada’s population lives within a 200-mile distance from the Canadian/U.S. border. Just over 61 percent of the population live in the provinces of Ontario and Quebec, which lie directly above the center of the of the U.S. population, which is geographically separated by the Great Lakes. It is no wonder that both countries are each other’s largest trade and investment partners.

As logistics has grown to be one of the most important criteria for both foreign direct investment (FDI) as well as international trade decisions, it is worthwhile to take a closer look at logistics in Canada in terms of external global forces and competitiveness and internal infrastructure. Global Forces and Competitiveness

Canada is a natural resource based economy. Approximately 58 percent of Canada’s exports are commodities, particularly coal, oil and gas, potash, and iron and ore. Lumber, agriculture, fishing, and fertilizers are also major exports.

The latest global recession started in 2008 and the developed OECD countries were hit the hardest. Commodity prices soared, which helped Canada. Trade and investment (FDI) shifted to the emerging countries (ECs), most of which had significant natural resources. Financing flowed in, and many of these countries borrowed heavily to take advantage of the surging commodity prices. This was referred to as the “Super Commodities Era.”

By 2014 the Super Commodities Era was over, as the volume of world trade could not keep pace with GDP growth. Commodity prices collapsed very quickly. The economies of most countries that were major exporters of commodities were hard hit, and the global trade volume has tumbled along with commodity pricing. Oil-producing countries were hurt the most, with prices 60 percent below what they were just three years ago. So much commodity capacity has been on the global market that it is only now that commodity pricing is believed to be hitting the “lower trough.”

While the commodities downturn has slowed the Canadian economy to a sluggish level, capacity utilization rates in the non-commodity industries are high. This is good news; one rule of thumb in plant investment circles is when capacity utilization rates approach 80 percent, there is real pressure to build or create new capacity — new plants and facilities. However, one should keep in mind that in today’s globalized world, adding capacity does not necessarily mean the new capacity will be built at home, it can be built overseas.

To make matters worse, global social and political unrest is making the world — and as a consequence global investment (FDI) — a bit riskier. FDI flows have responded to this risk by shifting attention back to a much safer arena with FDI now focusing more on developed OECD countries and developing Asia. Again, this may be to Canada’s benefit as it is a stable, developed OECD country and well positioned with investment and trade with Asia. This is welcome news as Canada’s unemployment rate still hovers around 7 percent.

The easternmost provinces in Canada are not very densely populated. However, a major port is located in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and is the deepest of all of the ports located in North America. Halifax is a state-of-the-art port and handles containers, bulk, break-bulk, Ro/Ro cargo, and freight. It is rail-served by Canadian Northern (CN). Almost half of its cargo is to/from Asia via the Suez Canal. Major industries in the provinces of Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island (PEI), Newfoundland & Labrador, and New Brunswick include forestry, mining, and fishing.

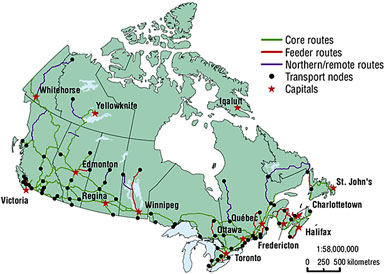

Moving westward, the provinces of Quebec and Ontario together comprise the largest industrial area of Canada, accounting for the majority of freight movement, including more than 80 percent of truck freight movement. The freight corridor running from Detroit, Mich., through Windsor, Ottawa, and Toronto (Ontario), and on to Quebec City is the busiest corridor in Canada. The Toronto to Quebec City portion is super-high density. Likewise the corridor running from Toronto and Hamilton (Ontario) and down to Buffalo, N.Y., is a main freight corridor.

Quebec province industries include utilities, forestry, mining, and aerospace, while Ontario province industries include automotive, manufacturing, and high tech. The Port of Toronto is the main port on the St. Lawrence Seaway. It has several container terminals as well as bulk, break-bulk, grain terminals, and an oil/liquid terminal. Montreal is served by both CN and CP (Canadian Pacific) railways. From Montreal, CN dips down south to Detroit and Chicago, goes west to Kansas City, Mo., and continues south to Memphis and New Orleans.

Western Canada is made up of four provinces along the southern border. Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia provinces’ industries include livestock, grains, agricultural equipment, oil and gas, potash, mining, and manufacturing. Winnipeg (Manitoba) serves as a gateway to the U.S. Midwest via highway and rail for both CN, which goes south to Duluth, Minn., and Chicago, and CP, which goes south to Minneapolis-St. Paul, Minn., Kansas City, Mo., and Chicago. Saskatoon (Saskatchewan) is a regional agricultural hub. Edmonton and Calgary (Alberta) are major players in the oil and gas industry and have intermodal rail terminals.

Canada is a developed country and a member of OECD and has become the 11th-largest economy in the world. Vancouver (British Columbia) is a port city on the Pacific Ocean above Seattle, Wash. The Port Metro Vancouver is a state-of-the-art port that handles roughly 50 percent of all container traffic for Canada. The port can handle the super Post-Panamax ships, has Ro/Ro service, large bulk and break-bulk terminals, and oil and liquids terminals, and is served by both CN and CP. Further north in British Columbia is Prince Rupert Port — also a state-of-the-art port with five world-class terminals. This natural deepwater port is served by CN railroad.

Canada is home to numerous international airports including Quebec, Montreal, Toronto, Calgary, Edmonton, Vancouver, and Winnipeg, among others. International air cargo is serviced by these airports as well. Likewise, Canada has one the most extensive pipeline networks in the world.

Rail & Trucking

Rail is king in Canada and is used widely due to the very long distances involved in freight movement. Declining shipping demand has hampered growth at both CP and CN, where shipping revenue and carload volume have dropped, including coal, crude oil, and grain. However, the railroads have been able to trim expenses and are poised to be in rather good shape when pricing and volume improves and predicted for 2017, when non-energy–related export growth should lead a recovery led by a lower Canadian dollar. Intermodal is widely available; however, trailer-on-flatcar service (TOFC) — also historically referred to as piggyback — is available in the U.S. but is not available in Canada.

The volatility of the Canadian dollar (CND) caused by the large swing in commodities influenced trucking freight as well. When the CND was stronger than the U.S. dollar a few years ago, shipping volume increased going north, as Canadian consumer demand was higher. Today, the opposite is occurring, there is a great increase in southbound shipping volumes as U.S. exports become more expensive to Canadians. The counter effect is that freight lanes and their volumes and pricing all follow suit. Head-haul lanes and back-haul lanes switch places as well, meaning it is now cheaper to ship to the U.S. from Canada than it is to ship from the U.S. to Canada. Investors and shippers into Canada must plan for occasional swings in the commodity and FOREX pricing by as much as 20 percent to 25 percent either way.

In Sum

The Canadian market from a logistics standpoint is indeed beneficial — depending, of course, on the purpose of the investment or trade. Rules and regulations are only slightly different between the U.S. and Canadian marketplaces, for example. The physical logistics infrastructure of Canada is in very good condition and trade/investment opportunities continue to attract businesses. More important is for investors and shippers to do their due diligence and have a close understanding of the landing costs as various external economic conditions influence the marketplace — the same as would hold true with any other country.