That said, to reap the benefits of this economic opportunity, real challenges in infrastructure and real estate must be addressed. The good news: there are solutions to community growth pains manifested by “man camps” and lack of roads, and municipalities now have the benefit of looking beyond their own experience and learning from recent experience of other cities and communities.

The Economic Opportunity

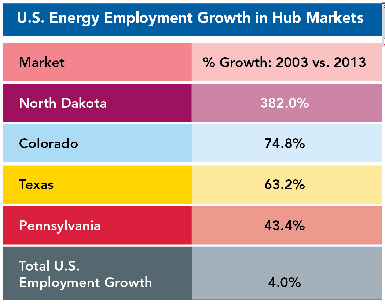

The opportunity posed by our new ability to access oil and natural gas reserves through horizontal drilling is enormous. According to industry reports from I.H.S. Global Insight, the domestic energy industry is expected to create more than 3.5 million American jobs by 2035, including 700,000 in the next two years.

Energy companies are likely to invest more than $100 billion in the next few years in Texas alone — home to the Eagle Ford and Permian Basin shales. In 2011, the boom created more than 38,000 jobs in South Texas and poured more than $500 million into local and state coffers, according to a report by the University of Texas at San Antonio, as published in the USA Today article, “Oil! New Texas Boom Spawns Riches, Headaches.”

Despite a seemingly “win-win” situation for energy companies and local economies, the domestic oil boom has created major infrastructure challenges for these states. The shale’s epicenters are often located in small communities that have undergone population surges from the hundreds to the thousands in a few short years. As a result, there is a significant lack of infrastructure, from buildings that house employees to roads and utilities that support operations.

When it comes to real estate, the demand for both commercial and residential buildings has driven energy companies to improvise with temporary solutions such as “man-camps” (explained below) and trailer offices that are not conducive to long-term productivity. As a result, local municipalities are looking for more optimal real estate solutions to support energy companies’ supply chains by developing infrastructure and working with developers in these communities to build additional housing, retail and office space, and industrial facilities.

- Infrastructure — While communities are funding new infrastructure projects, these large-scale installations often require longer time spans for government approvals than energy company land leases can accommodate. Municipalities handle the issue in different ways, often asking energy companies to fund and manage the infrastructure projects, and working with third-party experts to identify, manage, and execute the construction to accommodate basic needs such as electric, water, and roads. For example, electrical power is one of the most immediate infrastructure issues in the Eagle Ford zone so discussions are under way with the state of Texas and local utility firms to identify existing power lines and the best way to expand on the current lack of capacity.

Building sites are being driven both by access to electrical infrastructure as well as by the limited road infrastructure that can carry the load capacities needed by energy companies transporting heavy equipment, pipes bound for “laydown” yards, and underground drilling production components. Third-party service providers are helping energy companies, which are not experts in land use and real estate development, to address the need to ramp up quickly by analyzing tax records, government incentive programs, and real estate development opportunities so that these energy companies can meet their production speed-to-market goals. - Industrial/Production Facilities — When conducting land-use studies, municipalities must also take into account the large proportion of space required for production facilities. These facilities are highly specialized and differ significantly from properties required by other industries. For example, “down hole” companies need facilities in which to store their monitoring equipment — both the extensive computer rooms and the actual equipment that goes into the well. Many of the industrial facilities must store vehicles and drilling equipment indoors, particularly in the harsh climate of the Bakken Shale, and the size of that equipment can require ceiling heights up to 60 feet — triple that of a traditional warehouse.

The facilities must also meet critical health, safety, security, and environmental regulatory requirements to ensure that the activities onsite are safe for the employees and the environment. This demand for industrial space is impacting shale zones in an uneven way. For example, in the Pittsburgh area, the challenge is somewhat muted because there is existing, if outdated, infrastructure and real estate that can be repurposed; e.g., in one town, a former elementary school has become an operations center. - Housing — As energy company employees often outnumber a community’s permanent population by several times, housing is the most visible real estate challenge in shale plays — and often the most problematic. Worker demographics are overwhelmingly male, and as there are limited options for housing, most workers are unable to bring their families to the production site. This has resulted in the establishment of “man camps,” i.e., temporary housing that is taking place in trailers packed with single men earning high salaries, yet living in dorm-like conditions.

For a big picture perspective, JLL estimates that the energy sector’s impact on U.S. apartment demand likely contributed to nearly 25 percent of total unit absorption since 2002, an overall demand of approximately 165,000 units. The housing shortage is also creating demand for the limited number of hotel rooms available near production sites. Therefore, for visiting energy company executives or managers onsite for limited periods of time, the expense of visiting production sites has risen significantly. According to the JLL 2013 Energy Outlook report, U.S. energy markets have contributed disproportionately to the office recovery — representing 22 percent of recently increased office space occupancy in these markets. The lack of supply has resulted in skyrocketing hotel room rates. On a recent stay, for instance, a hotel room near Epping, North Dakota (permanent population: 109), required a three-day minimum stay at $267 per night. Oil and gas companies are turning to real estate service providers to help address the problem, bringing in real estate developers to build the apartments, houses, stores, restaurants, and schools.

These emerging projects are expected to reduce the amount of temporary housing and bring women and children into the communities.

- Retail — Much like housing, there are simply too few stores and restaurants to effectively serve the growing energy communities. Even during the recession, retail vacancy in Houston dropped 1.6 percent since its 2008 peak. Much like housing, as investors and retailers themselves become more comfortable with the long-term potential of these communities, stores and restaurants will begin to open at a more rapid pace. Municipalities generally welcome retail, particularly as an immediate source of tax revenue that can often be used to solve some of the other challenges such as the need for more roads and schools.

- Offices — In many of the small towns serving production sites, there is little suitable office space available. Extraordinary technological infrastructure is necessary to combat technical challenges in the field. Now picture that requirement operating out of temporary trailers. Most oil companies want to lease space, rather than purchase, when addressing these needs for the longer-term. Right now, many are integrating their office requirements into build-to-suit industrial facilities, but they’d rather not tie up capital to support real estate. Nevertheless, energy companies are now building office properties themselves, given that real estate is a major factor in speed-to-market.

Energy companies have also driven a revival in the real estate market in the Pittsburgh area. One new office campus hosts the regional headquarters for Shell, CNX Gas, and Exxon. Several million square feet of additional space has been leased since 2009 and is directly attributable to the energy industry, including a significant expansion by support services such as law firms.

Energy companies have also driven a revival in the real estate market in the Pittsburgh area. One new office campus hosts the regional headquarters for Shell, CNX Gas, and Exxon. Reaping Rewards Through Collaboration

There has to be a collaborative effort between energy companies, local municipalities, and real estate developers to optimize economic growth in shale zones. Energy companies are beginning to work with third-party consultants specializing in public/private partnerships to address not only infrastructure challenges, such as roads and utilities, but also broader community issues, such as schools and other services to support employees’ families.

While real estate investors and developers have oftentimes been hesitant in building permanent housing due to uncertainty in the production cycle and a viable exit strategy, energy companies are committing to significant real estate developments by pre-leasing apartments, offices, and industrial space, which takes the leasing risk out of developments and facilitates financing. Developers are also building properties flexible enough to adjust with the economy so investors are given multiple options for potential revenue generation. For example, a new full-service hotel under construction currently in Williston is incorporating a relatively easy way to convert the hotel into apartments if hotel demand dips. Similarly, an industrial warehouse can be built for multitenant use.

With shale zones developing solutions in “real time,” economic development agencies in neighboring states are now becoming proactive in managing expected real estate and infrastructure issues once production expands. Areas exhibiting this proactive approach include those in the Bakken Shale in eastern Montana and other locations west of the current drilling zones. This proactive planning will result in a net-positive situation for stakeholders as municipalities pre-plan real estate and infrastructure needs to facilitate production.