According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), employment in the U.S. increased by 156,000 in August 2017. The biggest gain was seen in manufacturing (36,000 new jobs), led by the continued strong performance of the automotive industry. In fact, manufacturing has added 155,000 new jobs to the U.S. economy since November 2016.

Further, in August 2017 manufacturing activity was at its strongest in six years. The Institute for Supply Management’s manufacturing index climbed from 56.3 percent in July to 58.8 percent in August — its highest reading since April 2011.2

Other industries that created jobs and reduced unemployment rates across the country in August were construction employment (28,000 new jobs), professional and technical services (22,000), computer systems and related services (8,000), and healthcare employment (20,000). Healthcare gains represent an ongoing expansion of jobs in that sector. Despite uncertainties with the Affordable Care Act and insurance coverage, healthcare has added 328,000 jobs in 2017 as of September.

A good example is New Jersey — for the first nine months of 2017, education and healthcare added 4,200 jobs — almost 20 percent of the 20,500 jobs created that year in the state. Similarly, in North Carolina, the largest employment gains in August 2017 were in education and health services, with 5,400 new jobs created, and Virginia is also seeing strong healthcare growth, especially in the Richmond area, where healthcare and social assistance programs have thrived, creating about 1,200 jobs year-over-year through the second quarter of 2017.

Hiring in other key economic sectors was more subdued or negative. Employment in food services, wholesale trade, retail trade, transportation and warehousing, information technology, financial services, and the public sector was fairly flat in August 2017.

High Unemployment States

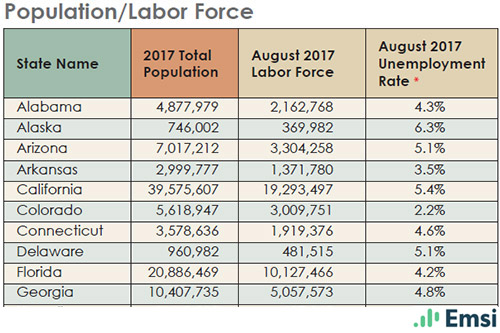

States with the highest non-seasonally adjusted unemployment rates as of August 2017 are New Mexico (6.4 percent), Alaska (6.3 percent), Louisiana (5.6 percent), West Virginia (5.4 percent), Ohio (5.3 percent), Illinois (5.2 percent), and Kentucky (5.2 percent). Numerous economic factors impact unemployment rates, including diversity of the economy, key industries, worker education, and government-supported job-creating programs. For example, both the New Mexico and Alaska economies are impacted by volatility in the oil and gas sector, seasonal work, and a heavy dependence on federal spending.

The August non-seasonally adjusted unemployment rate in Illinois was 5.2 percent, just slightly more than the previous month and representative of the state’s uneven economy, which overall lost about 3,500 jobs that month. Best job growth occurred in trade, transportation and utilities, education and health services, and construction; these gains were, however, offset by losses in leisure and hospitality, professional and business services, and manufacturing.

Kentucky is in a similar situation. With an August 2017 non-seasonally adjusted unemployment rate of 5.2 percent, the state’s job gains in construction, education and health, leisure and hospitality, trade, transportation and utilities, and manufacturing were countered by losses in retail, information technology, mining, and logging.

Having a low unemployment rate is a top goal of every state economic development department. The states with the lowest non-seasonally adjusted unemployment rates in August 2017 — North Dakota (2.1 percent), Colorado (2.2 percent), Hawaii (2.4 percent), Idaho (2.6 percent), New Hampshire (2.6 percent), and Nebraska (2.8 percent) — tend to have diversified economies with some high-performing sectors and strong educational systems. In fact, two of these states — North Dakota and Idaho — reached their lowest-ever (seasonally adjusted) unemployment levels that month since the state unemployment data series began in January 1976.

Although these ultra-low rates are the envy of other states, they can actually hurt economic growth because there are very few available workers for new jobs. For example, Colorado’s adjusted seasonal unemployment rate dropped to a record-low 2.3 percent in April 2017, a mark that has only been achieved four other times by any state in recent U.S. history. “When we get to unemployment rates this low, you can’t sustain the pace of job growth,” Ryan Gedney, senior economist with the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment, told The Denver Post.

Wisconsin has the same problem. Its seasonally adjusted unemployment rate was 3.2 percent in May 2017, the lowest unemployment rate the state has had in 17 years — down from the peak of 9.2 percent late in 2009 during the Great Recession. “The bottom line is Wisconsin’s economy is growing and adding jobs, and our biggest challenge now is finding enough skilled talent to fill openings employers have available,” states Workforce Development Secretary Ray Allen.

Not having enough workers is still a problem for states that are closer to the national average of 4.4 percent unemployment. In Massachusetts, for example, the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate was 4.3 percent in July (3.7 percent non-seasonally adjusted in August). Even as one of the most-educated states in the country, Massachusetts does not have enough qualified workers to fill the job openings that are currently available, especially for the skilled positions in many of the high-tech sectors, such as medical devices and healthcare. “Although the unemployment rate remains low, we continue to see persistent gaps between the skill sets of available workers and the qualifications needed for in-demand jobs,” Massachusetts Labor and Workforce Development Secretary Rosalin Acosta told The Boston Globe.

Proactive states are devising more creative initiatives to create well-educated and highly trained workforces. Right-to-Work States

Another factor impacting a state’s economic performance, job growth, and unemployment rate is its right-to-work status — this is especially true for strong manufacturing states, such as the entire Southeast U.S. In January 2017, Kentucky became the 27th right-to-work state; in February, Missouri became the 28th state to pass right-to-work legislation.

In an April 2017 study entitled “The Impact of Right-to-Work Laws on Labor Market Outcomes in Three Midwest States: Evidence from Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin (2010–2016),” author Frank Manzo IV, policy director for the Illinois Economic Policy Institute, wrote that “while right-to-work laws have statistically reduced both the unionization rate and average worker wages, they have also been correlated with lower unemployment rates in the Midwest.” Comparing these right-to-work Midwest States to their three collective bargaining counterparts, Manzo notes that the unemployment rate has fallen by between 0.5 percent and 2.2 percent more in right-to-work states. Michigan stands out in particular, with an unemployment rate that has dropped by 4.8 percent since Michigan’s right-to-work law took effect.

Other studies also confirm that right-to-work states have lower unemployment rates than non-right-to-work states. “Economists have been studying the economic effects of right-to-work laws for more than four decades, and while it is inherently difficult to isolate the effects of a single policy on economic performance, the weight of the evidence strongly and increasingly suggests that right-to-work laws improve economic performance overall,” writes Jeffrey A. Eisenach, adjunct professor at George Mason University Law School in a white paper for NERA Economic Consulting. “Right-to-work states have had lower average annual unemployment in every year from 2001 to 2014 compared to non-right-to-work states. On average, the annual unemployment rate in right-to-work states was 0.5 percent lower than in non-right-to-work states.”

However, the complex nature of the economic factors at play is demonstrated by the lack of a direct correlation between right-to-work status and overall unemployment rate. For the 28 right-to-work states, the non-seasonally adjusted unemployment rate ranges from 2.1 percent in North Dakota to 5.6 percent in Louisiana.

More Workers Needed

As noted, the overall low unemployment rate makes it more difficult to find qualified workers for current job openings, as well as planned expansions. Proactive states are devising more creative initiatives to create well-educated and highly trained workforces. Without them, growth will stall and companies will look elsewhere for their location and expansion projects.

Virginia (3.8 percent non-seasonally adjusted unemployment rate in August) is among those states that have created programs for reducing unemployment. And the Virginia Board of Workforce Development continues to work on longer-term programs and incentives designed to improve the state’s overall workforce quality. For example, its “FastForward” workforce credential grant program, carried out through Virginia’s community colleges, provides workers with short-term training programs that prepare them for high-demand career opportunities. The Virginia Workforce System Report Card tracks the progress of the state’s jobs initiatives, including the attainment of STEM-H (science, technology, engineering, math, and health) workforce credentials and degrees. The goal is to produce 50,000 STEM-H credentialed workers and become the top state in the U.S. by 2030 for workforce credential and degree attainment. Early results look good: industry certifications awarded to Virginia high school students rose significantly in 2016, with nearly 100,000 certifications awarded since 2011.

Another major educational effort is under way in Tennessee. In August 2017, the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate for Tennessee was 3.3 percent — the lowest for the state over the last 40 years. As in other states, this achievement has created job shortages across the state. In response, Tennessee launched several initiatives to improve the skills of its workforce.

“By 2025 at least half the jobs in Tennessee will require a college degree or certificate,” says Tennessee governor Bill Haslam. “In response, we’ve created innovative workforce partnerships and education reforms for skills in high demand. The result is a steady pipeline of qualified candidates for companies doing business in our state.”

One of these is “Drive to 55,” which aims to bring the percentage of Tennesseans with college degrees or certificates to 55 percent by the year 2025. Another is “Tennessee Promise,” an initiative within Drive to 55 that offers high school seniors tuition-free attendance at one of Tennessee’s 13 community colleges or 27 colleges of applied technology. “Overall, since the launch of Tennessee Promise in 2013, first-time freshman enrollment has grown by 13 percent,” adds Haslam. “The first class of Tennessee Promise students entered school and the workforce training pipeline in the fall of 2015. While this is certainly a mission for higher education, it’s also a mission for workforce and economic development.”