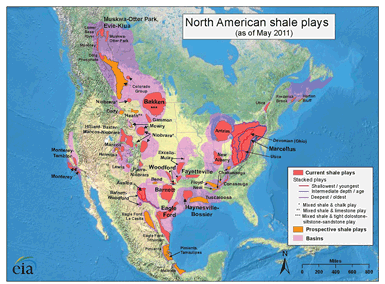

Production from “unconventional” reservoirs, called shale oil and gas, is transforming U.S. competitiveness for locations and the business climate for U.S. companies. Existing technologies have been adapted over the past 25 years or so to enable the production of oil and natural gas from geologic formations that wouldn’t have been possible in the past. These operations and the resulting flood of hydrocarbons are driving an enormous variety of infrastructure and manufacturing location decisions, many of which are independent on or accelerated by the recent drop in the crude oil price.

All of this leaves the U.S. well positioned to be the “new OPEC.” Already imports of foreign oil have been cut in half, from more than 60 percent as recently as 2006 to the 30–35 percent range. According to IHS, this shift contributed $283 billion to U.S. GDP in 2012 with 2.1 million jobs created, and added approximately $1,200 to the income of every U.S. household, mostly in lower utility costs. The impact is broad-based, and energy independence — a national priority for at least 40 years — is finally in sight.

- Innovation and regionalism;

- Resource-intensive nature of the operations;

- Low natural gas price; and

- Sheer abundance of the resources leveraging infrastructure.

Risk in developing these oil and gas resources has shifted from the old-time wildcatter’s 10 percent probability of success to a process of continuous improvement, driving down costs in an area of known hydrocarbons and rendering each well and shale play profitable.

Each shale play has its own unique set of geologic characteristics: depth, thickness, temperature, pressure, chemistry, compaction, consolidation, and so on. There are also opportunities or challenges presented based on availability of other resources, particularly water and sand. As a result, developing each play requires a unique solution that includes drilling techniques, mud and cement chemistry, equipment, well design, components of hydraulic fracturing, and so on that will produce successful results.

The companies taking the lead in this innovation — Schlumberger, Halliburton, and Baker Hughes — have all benefited from their partnerships and, as a result, have opened multiple large facilities in shale play regions, even to serve the Eagle Ford formation from San Antonio, only a short drive from their headquarters (and multiple other large facilities) in Houston. The functions performed at these regional locations include supply chain management, logistical support, and highly specialized R&D, and they can also serve as a staging ground for field operations, if needed.

Manufacturers have a need to be close to field operations as well. In December 2014, Buzzi Unicem announced a $40 million expansion and $260 million plant rebuild of its Maryneal, Texas, cement production plant — near the Cline Shale and the Permian Basin. This expansion project will increase production capacity from 550,000 short tons to 1.2 million short tons of cement per year and will be completed in early 2016. In addition to increasing capacity, this project will reduce plant fuel and emissions.

“The expansion of the Buzzi Unicem USA plant in Maryneal will not only help the company meet the needs of their current customers and expanding oil and gas industry in the Permian Basin/Cline Shale region, it adds stability to one of the foundation pieces in our community,” added Ken Becker, executive director of Sweetwater Enterprise for Economic Development (SEED).

In another recent example, Newpark Drilling Fluids announced in October 2014 that it would locate its drilling fluid production operation in Summit, Mississippi, to serve the emerging Tuscaloosa Marine Shale. This project will create 40 jobs in an area of tremendous potential due to its proximity to processing facilities and infrastructure.

The next factor driving shale-related locations is the resource-intensive nature of the industry operations, both for supplying inputs and transporting production.

Drilling, completing, and fracturing each well requires millions of pounds of sand, millions of gallons of water, equipment, chemicals, and many other resources. Even with more than 8,000 wells drilled so far in each of the Bakken and Eagle Ford shale plays, for example, the overall development effort is no more than 20 percent complete. The tens of thousands of forecasted wells will require decades to complete, and can therefore justify permanent facilities.

Texas and North Dakota are particularly well positioned for these operations to move forward despite significantly lower oil prices. And over the life of each well, multiple “frac jobs” and other operations will sustain demand for many of these products and support over the long term, mitigating the “boom and bust” phenomenon of more traditional oil and gas development.

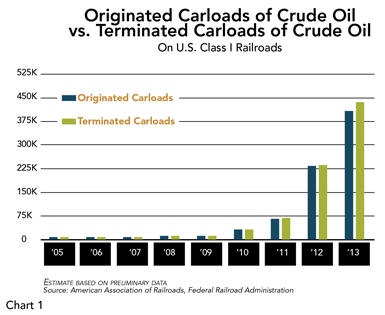

Class I and short-line rail, trucks, barges, and intermodal make up the new “flexible pipeline” for inbound supplies (primarily sand) and outbound production (primarily crude oil) to terminals or processing facilities. Although more costly for transporting crude oil than pipelines, this mode of transportation is proving attractive to companies because it gives them the ability to make real-time market decisions, thereby maximizing profitability (see Chart 1). As a result, manufacturing of rail equipment (especially tanker cars and hopper cars) is booming, and numerous intermodal facilities are springing up.

There are at least 19 of these types of facilities in North Dakota alone, with more in Texas and elsewhere. BNSF is leading the way with 15 million tons of sand shipped per year. Their just-completed Sweetwater Logistics Center in Sweetwater, Texas, will serve the emerging Cline Shale region and the Permian Basin operations of West Texas. The rail expansion on this 75-acre site included adding 7.5 miles of new track and three silos to hold 13,000 tons of sand. Future expansions of tracks are already under way.

And inland waterways are playing an important part in the “flexible pipeline” as well. And because the volumes of new crude oil production that must reach refineries in the Gulf Coast region are already large and rapidly increasing, time is of the essence. The award-winning Gulf Gateway Terminal project created, in only nine months, an efficient and environmentally sound hub to initially move 70,000 barrels of oil per day from one unit train (eventually expanding to two) to river- or ocean-going barges from a former bulk terminal and rail ferry at the Port of New Orleans. This adaptive re-use project leverages an important location on the Intracoastal Canal with access to the Mississippi River with significant rail access, and includes a sophisticated flood protection system developed post-Katrina. This additional transloading capacity improves the efficiency of local refineries, and will at full capacity be able to move more than four million tons of additional cargo.

Low Natural Gas Price

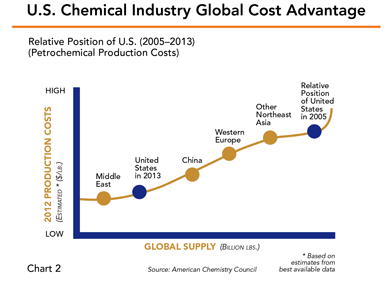

The abundance of natural gas (and the low price that resulted from the gas “bubble”) is a powerful stimulant for the U.S. chemical industry and is driving demand for new capacity. Since 2005, the United States has overtaken and passed Europe, China, and Asia and is overtaking the Middle East as the global low-cost leader of petrochemical manufacturing (see Chart 2). The American Chemistry Council (ACC) estimates that 197 projects, representing $125 billion in investment, have been announced as of the fall of 2014, approximately 64 percent of which is FDI.

And this cost advantage is paying off in re-shoring: Methanex, the world’s largest producer of methanol, for example, moved first one plant and then a second within a 12-month period from Chile to Louisiana. Their new locations represent a total investment of $1.1 billion.

Sheer Abundance of Resources Leveraging Infrastructure

This new competitiveness is particularly manifest in areas with strong energy infrastructure for manufacturers that need large quantities of the resource for feedstock or as a fuel. Many of the largest of these project announcements have leveraged inland waterways, pipelines, and other infrastructure to manufacture products, many of which will be targeting the export market.

Easily the most significant announcement is from Sasol, the South African refining and chemicals manufacturer. Sasol has announced a billion– billion complex in Southwest Louisiana. This project, if fully implemented, would comprise the largest single FDI in U.S. history, creating approximately 1,200 permanent jobs, and would start production in 2018. The company has given final approval on an $8.1 billion ethane cracker, and other products include diesel fuel and LNG.

But that is just one announcement among many. In 2010, Cheniere Energy was the first company in 35 years to receive export approval for LNG from its Sabine Pass liquefaction facility, and has already tripled its original capacity to six trains totaling 21 million tons/year of LNG over 20 years. In addition, Dow Chemical plans to invest $4 billion on projects and has started construction on a world-scale ethylene plant in Freeport, Texas; and Chevron Phillips has started construction on a $6 billion cracker in Baytown, Texas.

And other energy-intensive manufacturers are benefitting as well. Nucor, one of the largest steel manufacturers in the U.S., negotiated a 20-year agreement with a gas producer, guaranteeing a long-term supply at a low cost for their $3 billion Louisiana direct-reduction-iron (DRI) facility in St. James, Louisiana, that today produces 5.5 million tons/year of sponge iron. At the time of the announcement, Nucor cited a stable, long-term supply of low-cost natural gas as a critical factor in its location choice.