The Coming Battle: Public or Private Works?

The stage is set for battles on several fronts: which projects will be chosen? How will they be funded? Do existing, ongoing projects qualify? And how will the plan be structured?

Rather than the usual straightforward appropriation/authorization process based on greatest need, the Trump approach envisions a system of tax cuts and credits for corporations, plus an “infrastructure bank” for projects. This sounds like privatization of public works projects on a massive scale. Even more problematic for transportation and logistics, “Private investors would only fund projects that have tolls or user fees that can recoup investment costs. Therefore, critical infrastructure needs like repairing aging pipes, deepening ports, or fixing existing roads and bridges without tolls may go neglected under Trump’s plan,” according to a report by The Hill.

So what might an infrastructure plan mean for logistics and goods movement? “Infrastructure investment is one key to improving productivity, and therefore business profits and employee wages. Wisely targeted investments can lift the standard of living over time. For industrial real estate, better infrastructure creates new opportunities for development and for businesses to improve their supply chains,” says Robert Bach, Director of Research – Americas, Newmark Grubb Knight Frank.

Ports/Intermodal Rail

Many port projects involving dredging as well as road and intermodal rail access are either in the advanced planning and funding stages or are ongoing in order to accommodate the fleet of mega-containerships (18,000 to 21,000 TEUs) coming into service as a result of the Panama Canal expansion project that was completed in 2016. Many have funding regimes in place, so a new infrastructure program likely would have little impact on them.

One example is the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey’s Bayonne Bridge project to raise the roadway to 215 feet to accommodate the passage of larger vessels into New York harbor. In 2013, the port authorized $1.29 billion for this project, funded entirely by the port authority. It is estimated that from 2014 to 2018, the project will support nearly 2,800 jobs and $240 million in wages throughout the construction industry.

Similarly, the Port of Jacksonville’s new $30 million intermodal container transfer facility (ICTF) opened recently, providing on-dock rail service to the port’s North Jacksonville seaport terminals — the Blount Island Marine Terminal and the TraPac Container Terminal at Dames Point. The facility was constructed with $20 million in funding from the state of Florida and $10 million from U.S. Department of Transportation TIGER-grant funds.

DOT says the Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) grant program “supports innovative projects, including multimodal and multijurisdictional projects, which are difficult to fund through traditional federal programs.” Since 2009, the TIGER grant program has provided a combined $5.1 billion to 421 projects in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, Guam, the Virgin Islands, and tribal communities. These federal funds leverage money from private-sector partners, states, local governments, metropolitan planning organizations, and transit agencies. The 2016 TIGER round is leveraging nearly $500 million in federal investment to support $1.74 billion in overall transportation investments.

But demand for the 2016 TIGER grant program exceeded available funds; DOT received 585 eligible applications from all 50 states, and several U.S. territories, tribal communities, cities, and towns throughout the nation, collectively requesting over $9.3 billion in funding. It’s unclear how, or even if, a Trump infrastructure program that stresses private capital investment based on tax credits will work with the TIGER grant program. The stage is set for battles on several fronts: which projects will be chosen? How will they be funded? Do existing, ongoing projects qualify? And how will the plan be structured

The same can be said for the FAST Act, which established a “National Multimodal Freight Policy” designed to identify strategies and best practices to improve intermodal connectivity and the performance of the national freight system. FAST set up a discretionary freight-focused grant program to invest $4.5 billion over five years and established a National Highway Freight Program providing $6.3 billion formula funds over five years for states to invest in freight projects on the National Highway Freight Network. Up to 10 percent of the funds can be used for intermodal projects.

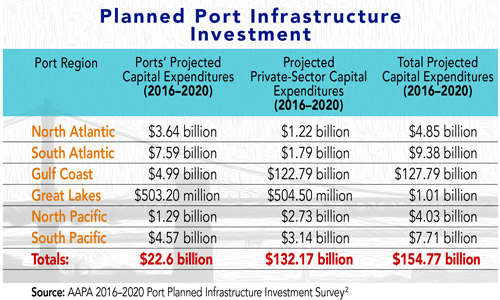

The American Association of Port Authorities (AAPA) recommends that the Trump infrastructure plan embrace and include the TIGER and FAST programs at increased funding levels. In a letter to the Trump transition team, AAPA noted, “Local port authorities and their private-sector partners are doing their part, with plans to invest over $155 billion in infrastructure over the next five years.”

Edward Hamburger, president and CEO of the American Association of Railroads, urged Trump to create a sustainable funding source for the Highway Trust Fund, such as a weight distance fee. He said any corporate tax reform in Congress should be paired with a deal for an infrastructure-funding source. But long-term funding solutions have long evaded Washington: the federal gas tax hasn’t been raised in over 20 years. Hamberger says the Trump administration should seriously consider solutions such as a weight distance fee “to establish a truly equitable system.”

Roads/Bridges

Whatever emerges under a Trump infrastructure program could focus on road and bridge projects. Those are the areas of greatest need, plus they provide the greatest opportunity for private investors to recoup and profit from their investments through fees and tolls. Whatever emerges under a Trump infrastructure program could focus on road and bridge projects. Those are the areas of greatest need, plus they provide the greatest opportunity for private investors to recoup and profit from their investments through fees and tolls.

The road and bridge report card by ASCE is barely passing: it gave America’s infrastructure an overall grade of D+ on its 2013 report card (the report is issued every four years) and estimated that roads, highways, bridges, water systems, schools, and transportation systems collectively will need $3.6 trillion in investment by 2020.

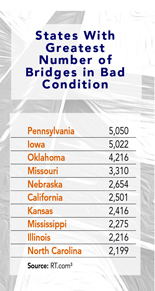

The raw numbers are distressing: 28 percent of major urban roads in substandard or poor condition, 240,000 water main breaks each year, 58,495 structurally deficient bridges. The 250 most-frequently-crossed bridges that rate as “structurally deficient” are on urban interstate highways, particularly in California. Nearly 87 percent of these bridges were built before 1970. States with the greatest number of bad bridges, as reported by RT.com are shown in the accompanying chart.

The Federal Highway Administration has estimated that $170 billion in capital investment would be needed on an annual basis to significantly improve road conditions and performance. My wish-list would be to make the following interstate highways — I-5, I-35, I-55, I-65, I-75, I-81, I-95, I-10, I-20, I-40, I-70, I-80, I-90 — at least three lanes in both directions; four lanes or more in proximity to major metros; and prohibit trucks in left lanes except on roads of fewer than three lanes in each direction or in emergencies to route around an accident; and also to fix the bridges on these routes. That would be a huge — and much needed — positive revision of the interstate highway system that could easily dwarf whatever public or privately funded infrastructure program is enacted by the Trump administration.