Incentives are still a powerful tool for advancing corporate location decisions, but they're no longer the backstop they once were. Projects are missing targets. Programs are changing. Compliance is becoming more complex. At Newmark, we’ve watched these shifts unfold firsthand while supporting clients across North America and around the globe. What we’re seeing now is a realignment of how incentives are structured, measured and delivered—and it's catching some companies off guard.

Projects are underdelivering. In nearly every sector, we’re seeing companies fall short of their original job and capital investment commitments. Sometimes it’s automation. Sometimes it's talent shortages, delays, FDA approvals or internal misalignment. In every case, it creates a ripple effect. Project milestones get delayed. Incentive agreements must be renegotiated. In some cases, incentives are reduced or lost entirely.

Take one recent client. The project was supposed to generate 400 jobs at an average wage of $70,000 and $100 million in investment. It delivered only 300 jobs—but those roles paid $125,000 annually. From a payroll tax perspective, the state was actually doing better. But on paper, the agreement had been breached. We stepped in to help make the case: The capital was spent, the economic value was delivered, the job count was just lower than anticipated. It required careful negotiation and trust between company and community.

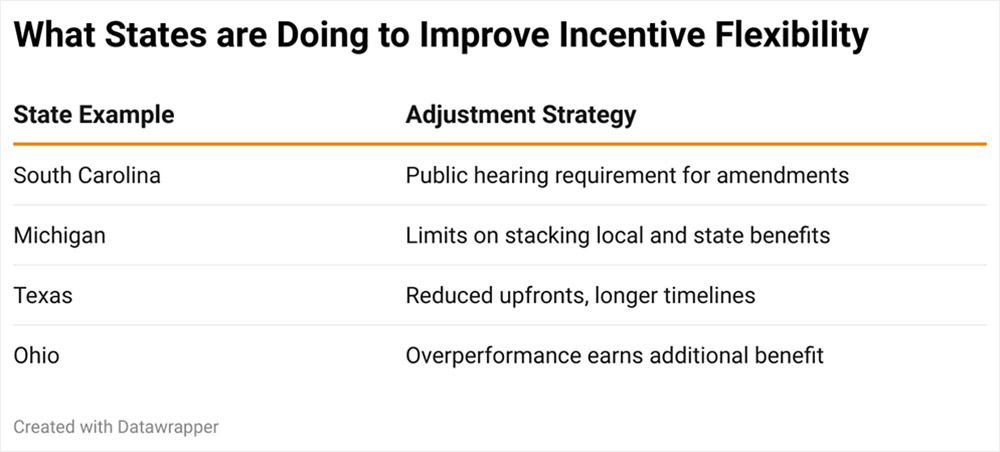

Some states are adjusting their formulas to reflect this new reality. We’ve seen weighted approaches that factor in both capex and jobs, sometimes allowing one to offset the other. But not all programs are built this way. Many remain rigid, designed for older models of job creation. If your agreement requires 100% compliance with no room for renegotiation, that’s a setup for conflict. Companies should push for built-in flexibility from the outset, especially when automation or variable timelines are involved.

300

Renegotiation is never ideal. It means returning to local boards, triggering new public hearings and risking community backlash. In places like Lancaster County, South Carolina, that can mean three council meetings and another full hearing. Agreements that lock in overpromised numbers make everyone’s job harder—including ours. Companies are better off setting conservative floors rather than aspirational ceilings. And when possible, communities should structure agreements that allow for grace bands—meeting 80% of goals without triggering a default, for example.

The compliance burden is bigger than ever.

Federal funding complicates things further. Over the past two years, the race for IRA and CHIPS Act money has forced companies to start site selection and incentives conversations much earlier. But many of those projects have now been rejected for funding—and it’s throwing entire timelines and investment strategies into disarray. Projects are being downsized. Some are being canceled outright. Others are pivoting to foreign investors, which can introduce new political risks, especially in communities wary of Chinese FDI.

Incentive timelines rarely match corporate timelines. A rejected federal grant can send a project back to square one just as local approvals are wrapping up. Companies need contingency plans. States and communities need to recognize that a failed federal bid doesn’t mean the project lacks merit—but it might need to be restructured.

Set floors, not ceilings, when projecting performance.

Megaproject fatigue is real. The past few years have been defined by a surge of supersized investments, especially in EV and battery manufacturing. But these projects are politically fraught, expensive to support and difficult to administer. The compliance burden alone can require companies to hire full-time staff just to manage reporting. Communities are beginning to reconsider their appetite for risk. Some are even relieved when we bring them smaller, more right-sized projects—125 jobs, $70 million—that might have been ignored in the past.

Data centers face a similar reckoning. Incentives are being reevaluated in nearly every state. Some legislatures want to eliminate them. Others are creating hybrid models where companies must choose between state and local benefits. The public is asking harder questions and, in many cases, demanding more reporting. We’re watching communities take a closer look at ROI and push back on giving away the farm.

125

Other sectors are seeing new opportunity. Life sciences is returning, with more manufacturing and R&D projects in play. Food and beverage is staying steady. Semiconductors, AI and electronics remain red-hot. But office deals are getting left behind. Post-pandemic, the economics of office space have changed. Renovations are expensive. Class C space is practically uninhabitable. Many states’ incentive programs aren’t designed to support these smaller, less capital-intensive projects. Office-to-residential conversions, where they’re happening, require different metrics entirely. You can't tie housing outcomes to job creation.

Inventory tax incentives are back in the spotlight. With tariff uncertainty and supply chain reconfiguration, companies are asking more questions about Freeport exemptions, foreign trade zones and other logistics-related incentives. If you’re in a state that doesn’t offer these, now might be the time to rethink that. These tools are part of how companies are insulating themselves against global instability.

Communities are rethinking how much risk they’ll take.

Everything is being scrutinized more closely—from community backlash on foreign ownership to public skepticism about megadeals to the actual enforceability of clawbacks. But the solution isn’t to avoid incentives. It’s to approach them more strategically. Companies must build realistic forecasts, ask hard questions about compliance terms and understand the political and economic landscape of their chosen location.

The incentive landscape in 2025 is not broken. But it is evolving. Flexibility, transparency and strategy are more important than ever. Get those right, and incentives still work. Miss the mark, and the cost isn’t just lost dollars—it’s broken trust.