ROI is often used as the metric of choice for corporate real estate and tax executives charged with determining which state and local jurisdictions offer the best investment environments. Politicians and public-sector economic development officials also lean on ROI analysis when crafting legislative incentive programs and determining appropriate levels of financial assistance for company-specific business incentive proposals. Although the inputs and outputs inherent to public and private ROI models may differ, both models ultimately inform public and private decision-makers where limited corporate resources and government revenue might best be put to work.

Manufacturing as the Industry of Choice

Economists have long held that employment within and capital investment made by high value-add companies provide more direct, indirect, and induced economic benefits. Given the choice between a “big box” retail outlet and manufacturing facility that is establishing operations at a publicly owned site, public officials often prefer the latter. Unlike the retail industry, the manufacturing sector typically pays higher salaries, and has a more localized supply chain, with higher economic multipliers attached to per capita employment and capital investment.

For example, the higher salaries paid by manufacturers directly impacts state tax revenue via proportional increases to both state personal income and sales tax revenues. Indirect and induced economic benefits are realized when local suppliers hire additional employees to fulfill contracts with a manufacturer (indirect) and the new hires at the manufacturing facility and local suppliers increase household spending patterns (induced).

Likewise, when determining which industries should be statutorily eligible for business incentive programs and to what extent companies should benefit from discretionary incentives, public officials and politicians will often choose manufacturing over retail. Why? In many cases, the answer is significantly higher ROI that results from higher salaries paid to workers. Competition among states to secure higher waged employment opportunities intensified with the onset of the 2008 recession. This competition was in large part responsible for the current proliferation of state sponsored “Quality Jobs” incentive programs.

Quality Jobs Incentive Programs

Nevada unemployment rates topping out at close to 15 percent at the recession’s peak, followed by Michigan and California at 12.5 percent and 12.4 percent, respectively. Rapidly increasing unemployment rates placed added strain on state budgets that were already experiencing widening shortfalls. The federal government responded by enacting the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA), a $787 billion stimulus package aimed to put the unemployed back to work via a variety of federal tax incentives, publicly funded infrastructure projects, and stop-gap funding for state and local governments.

At the same time, spirited debate was taking place in state legislatures across the nation regarding the states’ responses to the economic crisis. State incentive programs were front and center during these deliberations. Many state officials advocated that it was time to recalibrate and reload their economic development toolboxes, while others backed cost-cutting measures that sought to scale back or rescind incentive programs with an eye toward filling budgetary gaps. Ultimately, many states opted to either re-authorize existing programs (typically such re-authorizations included more stringent recapture and clawback provisions) and/or establish new job-creation initiatives with deeper incentives that were specifically designed to lure employers with highly paid workforces. Many of these so-called “Quality Jobs” programs in operation today were enacted or enhanced as part of larger state legislative responses to the 2008 recession.

Currently at least eight states (including Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Iowa, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Mexico, and Oklahoma) have a “Quality Jobs” or similar program that provides enhanced benefits above and beyond the state’s traditional jobs program. The programs’ names may differ (e.g., Georgia Quality Jobs Tax Credit Program – QJTC; Florida Qualified Targeted Industry Tax Refund – QTI; and New Mexico High-Wage Jobs Tax Credit Program), but all of these state programs target high-wage workers and provide significantly enhanced tax benefits to participating employers over traditional job-creation tax incentive programs.

How the Programs Work

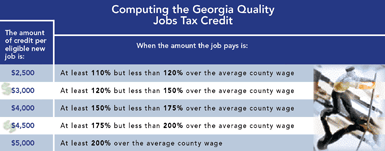

Georgia’s “Quality Jobs” program is effective for tax years 2009 and beyond and provides significant tax incentives for companies that create at least 50 net new “Quality Jobs” in a given 12-month period. Annual tax benefits range in value from $2,500 up to $5,000 per newly created “Quality Job.” Actual per-job tax credits are based on the percentage that a position pays above the average wage of the county in which the job is located. (See accompanying chart for explanation of how the credit is computed.)

Louisiana’s version of “Quality Jobs” provides gross annual payroll tax rebates to qualified employers that execute rebate contracts with the Louisiana Department of Economic Development.

Manufacturers and specified targeted high-wage industries that create at least five new jobs that pay at least $14.50 hourly are eligible to receive a five-year annual benefit that is equal to 5 percent of the applicable and incremental “Quality Jobs Payroll.” The incremental benefit increases to 6 percent for jobs that pay at least $19 hourly. The City of New Orleans offers a companion program to the Louisiana program that entitles eligible employers to a 2.5 percent rebate on sales and use tax otherwise due for machinery, equipment, and construction materials.

New Mexico’s High Wage Tax Credit Program offers refundable tax credits equal to 10 percent of wages and benefits for each new “high-wage job” up to a $12,000 per job maximum. The credit may be claimed in the year in which the eligible job is created and each of the three subsequent tax years. Eligible employers must pay their “high-wage employees” at least $40,000 annually ($60,000 after June 30, 2015) if the job is located in an urban area, or at least $28,000 ($40,000 after June 30, 2015) if the job is located in a rural area.

A Significant ROI

The stand-alone tax benefits associated with “Quality Jobs” incentive programs can be significant and a great way to offset initial costs associated with a newly constructed or expanded facility. For example, let’s assume a Georgia company operating outside of the retail sector proposes to create 100 new jobs that pay at least $65,000 and invests $10 million at an existing Cobb County facility. This proposed expansion project could potentially qualify for up to $1.5 million in Georgia Quality Jobs Tax Credits over a five-year period. By itself, this $1.5 million in Quality Jobs Tax Credits represents 15 percent of the proposed expansion project’s initial capital investment. Not a bad ROI at all, especially when one considers that the above excludes any additional state and local discretionary incentives such as local property tax abatements, state development training grants, and qualified sales and use tax exemptions that could move the ROI to upward of 20 percent.

Note: This article represents the views of the author only, and does not necessarily represent the views or professional advice of KPMG LLP. The information contained herein is of a general nature and based on authorities that are subject to change. Applicability of the information to specific situations should be determined through consultation with your tax adviser.