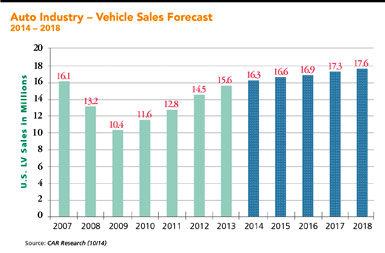

As sales increase, automotive production in North America is returning to pre-recession levels. With 11.7 million vehicles produced in 2014 in the U.S., employment is increasing to 715,000 workers, according to the Center for Automotive Research (CAR). By 2018, CAR is predicting that the industry will produce almost 800,000 more vehicles. The added volume, which is equivalent to four more assembly plants, should also raise employment to 780,000 workers by 2018.

With sales increasing, suppliers are struggling to meet several important challenges in the coming years. First, OEMs (original equipment manufacturers — or vehicle assemblers) are increasingly relying on suppliers. According to a recent KPMG survey of the automotive industry C-suite, one of the top five keys to success is for OEMs to outsource more noncore services to suppliers. Between 2013 and 2015, there was a 67 percent increase in the percentage of OEM executives who thought that outsourcing to suppliers is very important to their future success.

Next, the industry is facing big technological challenges, e.g. increased fuel economy requirements, which will reach their peak in 2025, as well as safety mandates. Currently the industry is focused on a “mid-term review,” scheduled for 2017, where the efficacy of the OEMs’ efforts to reach the 2025 targets will be analyzed. To meet the new fuel economy standards, OEMs are investing in new engine and powertrain technologies and lightweight materials. To help meet the safety challenges, the OEMs and their partner supplier firms are increasing the capacity of new onboard electronics for automated vehicles and safety devices such as lane departure warnings and active cruise control. These new technologies are bringing non-traditional supplier companies into the industry.

For example, electronics firms and integrator companies are needed to bridge the challenges of technology compatibility across the vehicle and its many subsystems. Innovation and collaboration are required to solve these challenges. New physical and virtual environments are increasingly necessary for testing the compatibility and functionality of many electronics systems, both individually and collectively. New entrants into the automotive supply chain from West Coast and Gulf Coast areas that are not traditional auto suppliers are looking for locations closer to the intellectual center of the automotive industry, and those that have many attributes similar to the locations they came from.

Finally, in the face of these challenges, the industry remains sensitive to cost. The OEMs have to adopt these new technologies, which require huge investments; but in order to maintain consumer demand, they also need to preserve the current price of the vehicle. Suppliers are facing giveback demands that allow the OEMs to maintain the current price structure.

Supplier/technology parks offer three unique benefits that could help OEMs and suppliers meet the challenges. If envisioned and structured properly, the parks foster an innovation ecosystem. Clemson University in South Carolina, in coordination with the International Center for Automotive Research (ICAR), has developed a 250-acre research park. Under the banner of systems integration, it has blended education and research programs to enhance product design, development, manufacturing, and advanced electronic systems research.

Second, the parks accelerate the development timeline. Project cycles are accelerating. Suppliers have less and less time to launch a project. An existing park targeted to auto industry suppliers and integrators overcomes the “chicken vs. egg” phenomenon. Developers contend that they will build a supplier park if customers exist who are willing to invest; meanwhile, suppliers say that once they have a need to build a new facility, they want to begin the next day. Oftentimes, the supplier has a contract in hand and time is of the essence. Someone has to make the first move.

Third, the parks reduce costs. According to a large national logistics firm, an OEM can save $1 million in annual shipping costs for every five miles closer that the supplier locates to an assembly plant. Importing components is getting expensive and risky.

For instance, Chinese logistics costs are now 18 percent of its GDP. The total cost of China’s logistics continues to rise 18.5 percent due to the rising price of raw materials, labor, and lending rates. Transport costs rose by 15.5 percent, storage costs soared 22.7 percent, and interest expenses jumped 24 percent. China’s logistics costs are more than double the average in Western Europe, Japan, and the U.S.

IDA-sponsored parks can also reduce redundant overhead costs. Embracing the “sharing culture” that is prominent in business today — e.g., Uber, couch-surfing, and Airbnb — suppliers can tap time-shared tool rooms and testing/validation centers to reduce these costs, while converting these activities from a fixed to variable cost. Not only are logistics costs high, the floods in Thailand and the tsunami in Japan demonstrate that it’s prudent to mitigate risks in the supply chain associated with natural disasters by locating supplier operations near the end customer. Even if this is redundant for the supplier, it will be less expensive to ship goods, and there is a large amount of risk moderation that is realized by the supplier and the OEM.

IDA-sponsored supplier parks also reduce real estate costs. With an industrial development agency serving as the developer and landlord, there are no private-sector administrative costs or added profit margins. Moreover, by tapping public-sector financing, the supplier parks can offer reduced lease rates from using potential tax-exempt financing, leveraging their own higher credit ratings, offering longer tenors on debt but shorter leases, and blending incentives such as tax-increment financing, New Market Tax Credits, direct loans, grants, and sales/use and property tax abatements or exemptions.

IDA-sponsored parks can also reduce redundant overhead costs. Embracing the “sharing culture” that is prominent in business today — e.g., Uber, couch-surfing, and Airbnb — suppliers can tap time-shared tool rooms and testing/validation centers to reduce these costs, while converting these activities from a fixed to variable cost.

An Example

In 2008, Harris County, Georgia, developed an industrial park and, during a difficult time in the automotive industry, adopted innovative strategies creating a vibrant ecosystem of support for Hyundai’s suppliers.

In West Point the county IDA packaged state and local incentives to reduce the operating costs for Hyundai’s suppliers and encourage their development. The centerpiece of its incentive was an IDA-sponsored lease. The IDA floated a bond of $6.5 million bearing an interest rate of 5.68 percent for 15 years. At the time of loan, Aaa corporate debt was bearing an average interest rate of 5.63 percent according to Moody’s. By comparison, the supplier was seeing financing costs from landlords in the 7 percent to 12 percent range. The bonds were general obligation of the county, payable from any funds including general funds. In addition, the county offered property tax abatement for 10 years and the state provided a $1 million One Georgia grant to pay for site prep and leasehold improvements. To integrate all of the incentives into one package, there was an Industrial Development Agreement between the IDA, the company, the city of West Point, and Harris County covering site preparation, water supply, sewer, natural gas and electricity, and permitting assistance.

In Sum

To be successful, supplier parks have to incorporate new thinking and new locations, as suppliers are suggesting that they will locate in urban cores if there are adequate supplier parks and customers are nearby. The parks depend on economic developers adopting a new mindset and becoming “community developers” serving the changing needs of the industry and its host communities. With communities and companies contributing, there is a virtuous cycle of enlightened benefit.