There's a lot of buzz around "Made in the USA" but turning that tagline into reality is more complicated. For U.S. textile manufacturers, competition from Asia and other countries has had a deep impact. More than 30 U.S. textile mills have closed in the past couple of years as businesses compete with countries where labor and other costs are cheaper.

"Just the cost of manufacturing in the U.S. is more," said Bill Rogers, president and COO of Mauldin, S.C.-based denim manufacturer Mount Vernon Mills, founded as a cotton yarn manufacturer in 1845. "We pay a living wage to people. We provide health benefits for employees, we provide savings options like 401(k)s and things like that, which is considered normal and standard here but are not normal and standard overseas. I can't pay $2 an hour, and force people to work overtime."

Like many textile manufacturers in the United States, Mount Vernon's business has ebbed and flowed. "We've had to embrace flexibility and change," said Rogers. "Going back to the 90s, we were a big denim producer and a lot of it just went to what I would call a five-pocket jean at a Walmart or Kmart. Today our denim is focused primarily on specialty denims — more high value stretch denims. We do a large business in fire resistant denim that's used in areas where for protected services or workers like electricians or oil well workers that need a protective fabric."

Mount Vernon isn't the only textile manufacturer to reinvent themselves. Denim North America (DNA), founded in 2002, produced denim for a number of well-known brands like Levi's, Wrangler, Gap and Polo. But price competition from China, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Egypt prompted brands to shift their supply chain and slowed demand for DNA and other traditional U.S. denim manufacturers. That shift prompted DNA to migrate its denim plant to a new type of product line in early 2018, shifting to specialty technical and industrial fabrics under a new name: DNA Technical Fabrics. Today, DNA Technical Fabrics' operation spans 280,000 square feet and employs around 150 people.

In the 1990s we made half of our apparel here for the U.S. market. Now we are at 2 percent.

Cone Denim is yet another example of how price competition shifted supply and value chains. Cone, founded by brothers Moses and Ceasar Cone in 1891, started weaving denim at its first mill — Cone Proximity Mill — in 1895. Like many textile manufacturers, the mill was located in Greensboro, N.C., close to cotton fields, warehouses and rail lines.

"When they say the South has good bones for textiles, it's like it's literally built into the infrastructure," said Beth Land, president and founder of Land Strategies, a site selection consultancy that has worked with textile manufacturers and other manufacturers.

Cone started manufacturing denim at its White Oak Mill in 1905, and by 1910 that mill was supplying a third of the world's denim.

Fast forward to 2017. Declining demand and overseas competition forced its owner, International Textiles Group (ITG), to shutter the textile mill. That closure marked the end of an era. White Oak was the last mill in the United States that manufactured selvedge denim — known for its durability and authentic heritage quality. Today, Cone continues to serve customers through its mills in Mexico and China utilizing modern equipment.

While the U.S. textile manufacturing industry has shrunk considerably, the remaining operations have embraced innovation, sustainability and the creation of strong bilateral trade relationships with Western Hemisphere partner countries.

"When China acceded to WTO ... a steep decline and the hardest hit decline in our industry was the cutting and sewing operations. That hypercharged the movement of that part of the supply chain, which is the easiest to offshore because you can unplug a sewing machine, to the lowest cost producers both in China and in Asia. And that was a sucking sound out of the United States," said Kim Glas, president and CEO of the National Council of Textile Organizations (NCTO), which represents every segment of the textile industry. "In the 1990s we made half of our apparel here for the U.S. market. Now we are at 2 percent."

That's a big reason why the tariff and trade announcements are being so closely watched by U.S. textile manufacturers. Tariffs on certain so-called "qualified goods" could easily disrupt an established supply chain between U.S. textile manufacturers and their Western Hemisphere partner countries under USMCA and CAFTA-DR.

"We export 70 percent of what we make — fibers, yarns and fabrics predominantly — to our Western Hemisphere trade countries to finish it and it comes back under the agreement duty free," Glas noted, emphasizing that "we made sure there were strong rules in [the trade agreements] that in order to get duty-free trade to the United States market for textile and apparel, essentially 100% of the components need to be made in the United States or the region."

Realistically, the edict I've given to our people is if we get what I call a hit new product, at the most, we've got a two-year run on it before it's knocked off in Asia.

U.S. exports of man-made fibers, yarns, fabrics and apparel topped nearly $23 billion in 2024, with USMCA countries accounting for $12 billion and CAFTA-DR countries accounting for $3 billion. In fact, Canada and Mexico represent $20 billion in two-way trade with U.S. textile manufacturers, according to NCTO.

The Western Hemisphere partnerships are not just financially fruitful, but also mutually beneficial from a labor standpoint, supporting more than 2.6 million workers throughout the hemisphere.

"It works and I think it's also good policy for our country," said Rogers. "If our neighbors are having a living wage and having a sustainable lifestyle, I think that's better for the U.S. too."

So far, the U.S. Administration has made tariff and trade decisions that are favorable to the U.S. textile industry, including eliminating the "de minimis" loophole that allowed hundreds of dollars' worth of cheaper products to flow into the United States from China duty free without any scrutiny. "Most of it is textile products crushing the industry as a whole in the Western Hemisphere," said Monte Galbraith, president of DNA Technical Fabrics.

While industry experts applauded the end to the de minimis loophole, others took a skeptical view. "We expect that to look like almost playing Whack a Mole that all of sudden you start seeing operations just like that pop up in neighboring countries over there and flowing in through de minimis," said Rogers.

De minimis dates back to the 1930s. Congress enacted it in 1938 to help streamline customs processing for small value items to ease the process for tourists who wanted to bring back souvenirs or gifts. Initially the threshold was $5 for gifts and $1 for other items. In 1994, that figure was raised to $200, and in 2015, the threshold was hiked to $800. And China has been the biggest beneficiary.

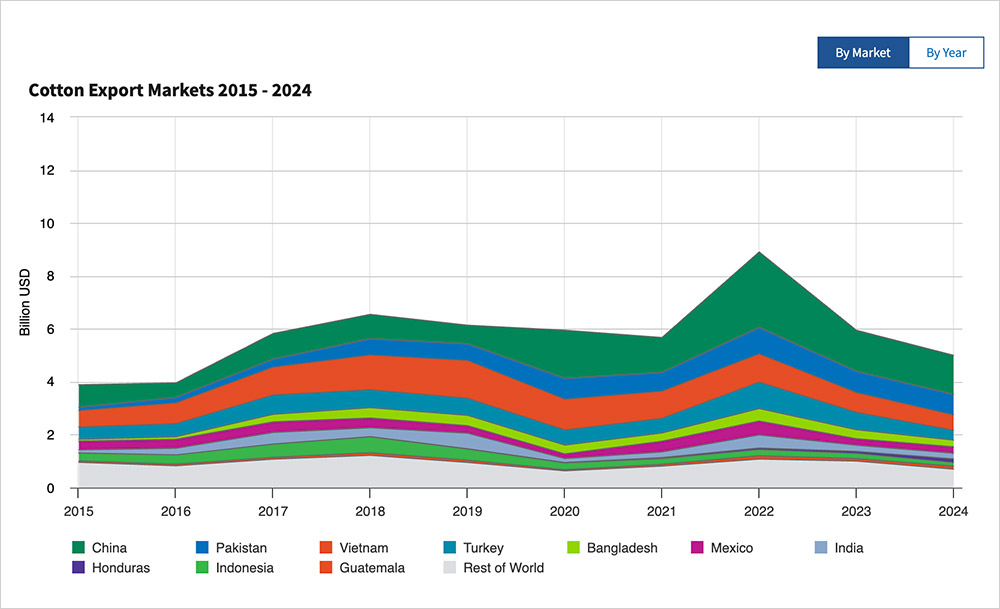

Roughly 85% to 90% of the cotton grown in the United States gets exported as cotton fiber, largely to China and Vietnam.

"When all that legislation was put into effect, nobody foresaw the rise of ecommerce and fast fashion and all that," said Rogers. "You literally have airliners flying into the U.S. multiple times a day, completely loaded with import goods that are not inspected, they're not tariffed."

Eliminating de minimis should help ease the impact of that loophole, even if it's just temporary. But industry experts are hoping for more concrete actions that will stick. "What is the trade policy going to look like over the next five years. I think that that is what everyone is following right now," said Glas.

"A lot can change in a hurry," added Rogers. With tariff uncertainty and recession fears underpinning the economy, domestic buyers are being cautious. "Nobody wants to get caught with the wrong inventory mix if the tariff situation changes."

Investing in Innovation

In order to stay competitive, U.S. textile manufacturers have been nimble and swift to embrace innovation.

"We have had to embrace flexibility and change. We have had to focus a lot more on specialty products, a lot more diversification in your product line," said Rogers. DNA Technical Fabrics was an early adopter of spotting that gap. As domestic demand waned for their traditional denim jeans, they quickly shifted focus to meet rising demand for denim used in fire retardant garments, industrial applications and military uses. Mount Vernon Mills has done much of the same.

"There are some pockets of business like that where there is a dedicated U.S. base," said Rogers, but you have to continually look to innovate. Eventually that market will get saturated, so textile manufacturers are always investing in research and development (R&D) to stay relevant.

"Realistically, the edict I've given to our people is if we get what I call a hit new product, at the most, we've got a two-year run on it before it's knocked off in Asia," said Rogers. "So you have to be constantly recreating yourself."

Unraveling the Cotton Supply Chain

The United States is among the world's largest cotton producing countries, ranking behind China, India and neck-in-neck with Brazil. Roughly 85% to 90% of the cotton grown in the United States gets exported as cotton fiber, largely to China and Vietnam.

That's where the supply chain can get complicated.

The exported cotton fiber gets spun into yarn, say in Vietnam for example. From there it may get sent to China to be turned into fabric, and then returned to Vietnam to be cut and sewn into a final product before it gets re-exported to the United States.

"So it's not necessarily straightforward in terms of the fiber going out and then all of the transformation occurring and then the garments coming back to us. There can be a lot of back and forth that can occur in different supply chains in different countries," explained John Devine, a senior economist at nonprofit Cotton Inc., which advocates for the cotton industry.

There are some U.S. spinning operations but only a fraction of what is grown is spun into yarn. U.S. famers have grown roughly 15 million bales of cotton annually over the past several years. Roughly 13 million of those get exported, with the remaining 2 million being spun into yarn that goes to Central America, where it gets turned into garment form and returned to the United States under CAFTA-DR.

Like other U.S. textile businesses, the combination of free trade agreements under NAFTA and China joining the WTO in 2001 drove U.S. cotton consumption sharply lower. In the late 1990s, the United States was consuming 10 million bales of cotton. The current crop for U.S. consumption is estimated to be 1.7 million bales.

While tariffs may be good for some, they are disruptive to the cotton industry. On a pound per pound or item per item basis, there's more value in apparel than fiber so it will inevitably create some trade imbalance merely because of the value added that occurs the further you go downstream in the supply chain.

At the end of the day, one of the biggest challenges for the cotton industry is building demand.

"On the one side, you don't want to be too expensive compared to competing fibers. But on the other hand we also need to have a profit opportunity that we can present to our farmers around the world so that they're encouraged to plant cotton rather than other crops like corn, soybeans, peanuts or something else," said Devine. "We've got to thread the needle between both sides of that equation. We need to be profitable enough producers but not too expensive to get us out of the market."

The silver lining may be several years out but the cotton industry is taking an active seat at the table. "Commodity markets are very volatile and of course the trade environment has been very volatile and will continue to evolve over the next couple of years," said Devine. "There's just so much uncertainty now in terms of where things might fall but cotton is highly globalized and going to be central to these discussions around changes in globalization that are occurring right now."

Sustainability is Built into Strategy

Anyone who touches the textile business will be quick to say the industry has always embraced sustainability all along the value chain.

"A lot of cotton growers will tell you they've been in the sustainability business as long as they been in business," said Devine. "Any input they put on their field is a cost to them so they've always been interested in keeping their costs down which of course made them more sustainable as well."

Commodity markets are very volatile and of course the trade environment has been very volatile and will continue to evolve over the next couple of years.

Cotton Inc. tracks sustainability measures on a whole range of data points, and Devine pointed to the fact that cotton farmers have been producing more with fewer acres as one example of sustainability.

Cotton, by its very nature, is sustainable. "We are a natural fiber [and] if left in a natural environment, we'll decompose," said Devine. As a plant, cotton absorbs carbon from the atmosphere, and as Devin reiterated, cotton "comes from the earth and goes back to the earth given the opportunity."

Consumers and retailers increasingly demand transparency around the entire supply chain, and U.S. textile manufacturers have been leaders on the environmentally friendly value chain.

"A lot of the companies have embraced increased traceability of their fabrics and suppliers to make sure that we don't have bad stuff leaking into the marketplace," said Rogers. "You're seeing a lot of companies not waiting on regulations to hit before they migrate out of things."

For example, Mount Vernon Mills transitioned out of "forever chemicals" known as PFAS several years ago even though the regulatory ban won't start to kick in until next year.

"Our industry has been on the leading edge of [sustainability]," said Glas. "It makes business sense to utilize waste, even their own waste, to reprocess it and put it back into their manufacturing operations. We have plants that are using recycled bottles, putting it back into chips, making it into yarn, into fabric."

Others are also innovating with natural fibers to avoid microplastics, and more detailed product safety certifications are becoming standard.

Sustainability isn't just about production. It extends to the workforce. "A lot of people, when they think of sustainability, they think about the pollution side of the world. Sustainability is also making sure somebody can have a living wage," said Rogers. "Sustainability is every person's job in our organization."

Navigating a Challenging U.S. Labor Market

Southeastern states have always been the hotbeds for textile manufacturing because of their close proximity to raw materials like cotton, big warehouses and accessible railway transport. "Culturally and historically they were there," said Galbraith.

The region is still the largest hub — Georgia, North Carolina and South Carolina continue to be the top three states for textile jobs — but it has shrunk considerably as many jobs moved overseas. Consider North Carolina. According to data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve, employment in Textile and Fabric Finishing and Fabric Coating Mills in North Carolina declined 90% from 1990 to 2024, with the biggest drop seen between 1996 to 2009 (80%).

When NAFTA was signed into law in 1994, there were more than 470,000 people working in textile mills in the United States, according to Labor Department statistics. By 2009, when CAFTA-DR went into full effect, that figure had dropped to 134,000, and by the time USMCA was implemented, the number of people working in textile mills had shrunk to 92,000. Today, there are about 85,000 workers.

It's just cheaper, and there are less stringent labor laws and controls in other countries. "You hear a lot about China, which has been a big one, but we see a lot of fabrics flowing in from countries like India, Pakistan," said Rogers. "And on the knit and cut and sew side, you see a lot of countries like Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Bangladesh are all big players in the market."

Southeastern states have always been the hotbeds for textile manufacturing because of their close proximity to raw materials like cotton, big warehouses and accessible railway transport.

"If you were surprised by it, you just were not paying attention," added Galbraith.

And those jobs aren't coming back anytime soon. "I think that would be difficult," said Rogers. "Once a mill has been shut down and that labor force has been reabsorbed into other areas, it would be difficult to get them back."

"When we look at the spinning stage, there's not a tremendous amount of labor involved so there is some potential for that," said Devine. "But as you move further downstream in the supply chain, you've got more labor that's being added. Particularly when you get to cut and sew, a lot of our garments are still assembled by human hands and labor costs can be expensive."

"With automation, things could potentially come back but without automation, I think it will be difficult to see, particularly the cut and sew, coming back to the U.S.," he added. "There's also questions about 'are there Americans that have the willingness to sit in a factory and make garments all day and will we be able to pay them enough to do that and be cost competitive?' It's a huge question."

Glas thinks there's a case to be made for some cut-and-sew business to return, but it's unclear on what scale. "We believe there could be a lot more onshoring of our supply chain, whether that's upstream components or the cutting or sewing," she said. "We are highly automated, highly sophisticated. You can use automation for cutting and sewing that employs workers to use machinery for high wage jobs [but] right now, we can't onshore all of it," she added, citing unfair trade practices in China and Asia.

But given the current trade environment, most people are taking a cautious approach. "Until there is more certainty from a tariff perspective, I think there's going to be very little investment happening," particularly around retooling machines and increasing automation, said Land.

There's no sign that U.S. manufacturers are considering building new mills. "I don't think you're going to see a lot of greenfield development," she added. "It's a really high, capital-intensive business with relatively low margins so I feel that the firms that are out there that are retooling are doing it in the real estate assets that they are in."

Meanwhile, what's happening to the closed physical operations? Some older cotton mills — typically brick-type warehouse buildings that are located in downtown areas — are being converted into apartments and wedding venues.

A recent example is the 800,000 square-foot Judson Mill complex in Greenville, S.C., which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2018. Founded in 1912, and originally known as Westervelt Mill, the mill manufactured "fine goods" fabrics and was best known for being the first Southern mill to produce DuPont's rayon. In 1913, the owner passed the mill onto former Furman University Professor Bennette Greer, who renamed it after his mentor, Furman Professor Charles Judson. Deering Milliken Co. (now Milliken & Company) took over operation in 1933, eventually owning Judson Mill, expanding and innovating, and investing in research & development.

Two years after the mill ceased operating in 2015, Taft Family Ventures and Belmont Sayre Holdings bought the site and have been moving forward with an $18.9 million commercial renovation. The first phase includes the conversion of a 107,269 square foot warehouse building into a mixed-use property that will include apartments, retail and nonprofit businesses. The Innovate Fund is providing $16.5 million in New Markets Tax Credits. The project is also being supported by loans, federal and state historic tax credits, and credits from the South Carolina Textile Communities Revitalization Act, which "provides a credit for the renovation, rehabilitation, and redevelopment of abandoned textile mill sites in South Carolina."

But many of the more modern factories that housed spinning operations in the late 1990s and early 2000s are not in ideal urban locations and are largely sitting dormant.

"There could be potential for there to be an uptick in textile manufacturing if the tariffs hold but we don't know if they will or not," said Land. "But if that does happen, I don't think we're going to see a bunch of greenfield development."

Leveraging Innovation and Policy for a Competitive Edge

Because U.S. textile manufacturers have had to be on their toes to remain competitive, they are constantly investing in R&D to stay relevant.

"Our industry has been the hardest hit by unfair trade practices. No question about it," said Glas. "In order for us to compete, we've had to automate, and innovate and put sustainability at the top so that we're servicing our customers with the latest and greatest products."

Until there is more certainty from a tariff perspective, I think there's going to be very little investment happening, particularly around retooling machines and increasing automation.

Mount Vernon Mills acquired Wade Manufacturing Company's yarn spinning and weaving facility Rockingham, N.C., in 2022, to transform into a vertically integrated operation from yarn production to finished fabric in certain products. "Since then, we've been able to double the workforce and increase the production out of the operation. So, there's a lot of capacity still left here even with all the closures that could be expanded."

Mount Vernon also operates on a four-day schedule broken into two 12-hour shifts. "If production needs to be ramped up we could look to add an additional shift," said Rogers. "The labor and training would be hard but it would not be unsurmountable."

It would also include some financial investment at the outset. "In a yarn mill, things like air filtration is a big one-time capital expense that everybody's already done. So once the infrastructure is already there you can add additional productive machinery inside that infrastructure, which a lot of the mills that are still here have still done," said Rogers.

As for cut-and-sew operations that produce the finished products, experts agree that's a harder sell, and more capital intensive.

"The best options there is for those to reopen in this hemisphere in countries like Mexico or the CAFTA-DR countries, where you do have a cheaper labor rate and you've got a skilled workforce already there that's underutilized in the cut and sew arena," said Rogers.

Creating new tax policies could also incentivize retailers to re-shore or nearshore some of their business, giving the U.S. textile manufacturing industry a boost.

"Sourcing executives who work for retailers, they don't manufacture," said Glas. "They buy. And they will switch sourcing based on long-term certainty about policy."

That's where the Americas Trade and Investment Act (Americas Act) comes in. Introduced by Sens. Bill Cassidy, R-La., and Michael Bennet, D-Colo., and Reps. Maria Salazar, R-Fla., and Adriano Espaillat, D-N.Y., in 2024, the bipartisan bill includes $14 billion in new incentives for textile recycling and reuse development to support a domestic circular economy, and a 15% net income exclusion for qualified circular businesses (reuse, recycle, repair, etc.). There are also loan provisions to help cover the cost of moving inventory, equipment and supplies from China, and additional tax credit incentives for nearshoring and reshoring expenses.

"There are huge opportunities with the right policy frameworks to grow the industry significantly," said Glas. Nearshoring and reshoring would position retailers and U.S. textile manufacturers with the ability to speed up the entire supply chain from inception to market. It would also allow them to jump on trends and better compete against fast fashion.

"Foreign imports are the biggest challenge," added Rogers. "You have a lot of players globally that are paying substandard wages, they may have product certifications but I've traveled in Asia, I've seen these operations. There's a lot of corner cutting that goes on. That, at the root is our biggest issue."

It's also about flipping the script when it comes to specialty fabrics. Rather than trying to recreate the same specialty fabrics coming out of Asia, U.S. textile producers are embracing new fibers, new chemistries when it comes to dyeing and finishing, and finding ways to increase product wearability.

"The U.S. as a country we've embraced cheap and disposable, which is not a very sustainable model," said Rogers. "I go back to product quality [and] product durability," he added, noting that some major brands are starting to see the value of having manufacturing "closer to home" and are considering reshoring some things, although no one has come out with any public pronouncements yet.

"To be a U.S. textile company you have to be the most competitive in the world in order to compete on the most unlevel playing field in the world," emphasized Glas.