The warning signs are everywhere. Ford CEO Jim Farley, recently said the company can’t fill five thousand mechanic jobs even at $120,000 per year.

“A bay with a lift and tools and no one to work in it — are you kidding me?” he said.

The automotive giant’s struggle is a snapshot of a broader industrial reality: as billions pour into U.S. factories and clean energy projects, the skilled labor simply isn’t there.

To explore this skilled trade gap more deeply, Area Development partnered with Lightcast, a big-data company that pioneered the collection and analysis of information on the labor market, and they helped provide a uniquely curated view of the skilled-trades pipeline — drawing on federal apprenticeship data, college completions, and employment projections — to reveal why workforce readiness has become the most important site selection variable in America.

Every major corporate investment begins with a simple question: Can we find the workers?

Today, the answer increasingly comes with hesitation. Across the U.S., manufacturers and infrastructure developers are hitting a wall of workforce constraints that could define the next decade of industrial growth.

Labor is now the first question in every site decision, not the last.

From semiconductor fabs in Arizona and Texas to clean-energy projects across the Midwest and South, companies are racing to build capacity. But as projects multiply, the pool of skilled labor isn’t keeping up. Employers are competing for the same welders, electricians, machinists, and maintenance techs that other sectors already depend on.

“Labor metrics are reshaping site selection. Companies now weigh workforce availability and training infrastructure as heavily as real estate costs. Incentives tied to upskilling and partnerships with technical colleges are becoming standard tools to mitigate skilled trade shortages,” said Ben Harris, head of Industrial Consulting at Cushman and Wakefield.

For corporate decision-makers, that reality has reshaped the calculus of site selection. Workforce risk — once a secondary concern — now rivals power availability and permitting speed as a top constraint on project timelines.

“When a company commits to a billion-dollar facility, it’s making a 20-year bet on talent,” said John Loyack, vice president of Economic Development and Workforce at the North Carolina Community College System. “The best states aren’t selling available workers; they’re selling their ability to train the next generation. Every project starts and ends with workforce confidence.”

The Numbers Behind the Pressure

To understand the scale of this challenge, Area Development and Lightcast built a dataset focused specifically on Skilled Trades Workers — occupations that rely on advanced technical or mechanical training but not a four-year degree.

1.7M

We combined Lightcast’s national employment projections (2022–2025) with 2024 completions data from community colleges, trade schools, and Department of Labor–registered apprenticeship programs. The goal: to see where the nation’s workforce pipeline is most constrained.

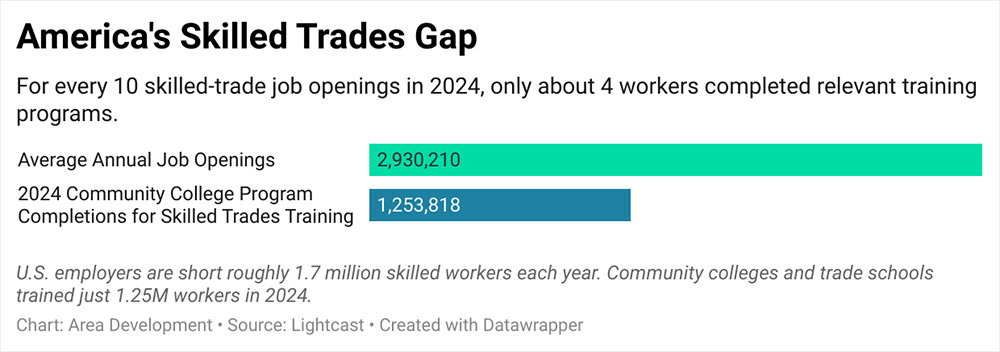

Each year, American employers report nearly 2.9 million job openings across these skilled trades. Over the same period, education and training systems collectively produce only about 1.25 million qualified graduates.

That leaves roughly four trained workers for every ten available jobs — a shortfall of 1.7 million workers annually.

“What we’re seeing is a structural shift and imbalance in the labor market that’s been building for decades,” said Josh Wright, executive vice president at Lightcast. “The U.S. is getting older. Birth rates are declining. And fewer young people — those we have — want to or are encouraged to work in the trades. Even as demand for technical and skilled labor rises, the education and training pipeline hasn’t kept pace — and that’s the core tension shaping every site decision right now.”

The demographic drought identified in Lightcast’s Rising Storm report compounds the problem, as an aging workforce exits faster than the pipeline can replenish it. As the U.S. doubles down on domestic manufacturing, clean energy, and supply chain resilience, this imbalance has become the hidden bottleneck in the nation’s industrial strategy.

“If you can’t find the people to build or maintain it, the project just doesn’t pencil out anymore,” said David Greek, CEO of Greek Real Estate Partners. “Labor is now the first question, not the last.”

The Industrial Moment: Building Faster Than We Can Train

After decades of offshoring, the U.S. is experiencing what many call a manufacturing renaissance — driven by federal policy, private investment, and geopolitical necessity.

The CHIPS and Science Act, Inflation Reduction Act, and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law together have triggered the largest wave of industrial construction since World War II. But those policies assume a workforce that doesn’t yet exist.

Lightcast’s Skilled Trades dataset makes that tension clear: industrial capacity is expanding faster than our ability to train the people who will build, install, and maintain it.

In sectors like semiconductors and nuclear energy — where precision and safety are paramount — the required skills take years to develop.

“As America grows its domestic semiconductor ecosystem and reinforces its global technological leadership, a highly skilled workforce will ultimately determine our ability to compete and fulfill the goals set by Congress and the Administration in the CHIPS and Science Act. Unfortunately, the U.S. faces a shortfall in the supply of skilled workers that the semiconductor industry must meet,” John Neuffer, President & CEO, Semiconductor Industry Association, said in a recent report.

4 to 10

The nuclear sector faces the same squeeze. The U.S. is investing heavily in small modular reactors (SMRs) and next-generation nuclear technologies, yet the workforce that operates and maintains them is aging out.

“God, like, it's hard enough for us trying to recruit people, and then you’ve got to fight with the other companies trying to get them,” said James Walker, CEO of Nano Nuclear. “They’re getting paid very nicely, but it’s worth it — if you don’t recruit them, you don’t build anything.”

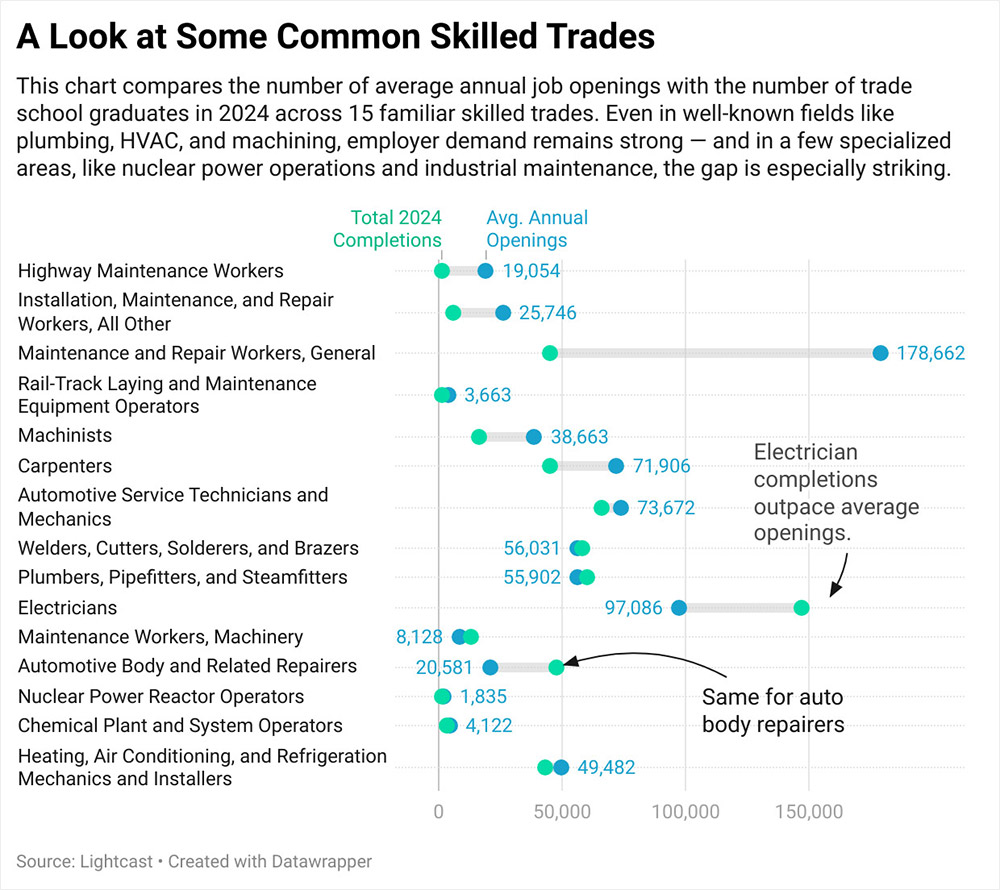

Electricians, plumbers, HVAC technicians, and machinists — the backbone of the industrial workforce — remain in short supply. Electricians are one of the few trades where graduates slightly outnumber openings; most others fall short.

Machinists face about 2.4 openings per graduate, maintenance and repair workers nearly 4 per graduate, and highway maintenance roles exceed 16 to 1.

These figures incorporate both traditional college completions and DOL-registered apprenticeship graduates, giving a fuller picture of how local training ecosystems are performing.

“The gap isn’t so much getting entry-level journey workers; it’s that transition all the way into superintendent and field leadership,” said Scott Canada, president of Renewable Energy at McCarthy Construction. “That foreman-to-superintendent step is really tough.”

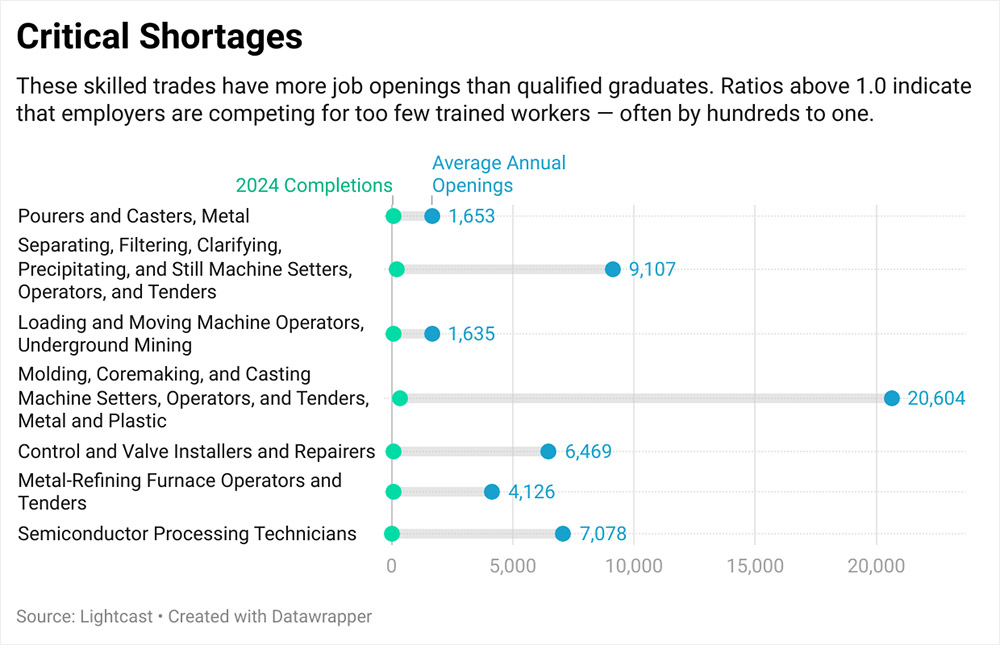

At the extreme end of the data are the roles with the smallest pipelines — occupations where training completions round down to zero in many states.

Semiconductor process technicians, furnace operators, and nuclear technicians show more than 100 openings per graduate. Even when apprenticeship completions are added, the gap barely narrows.

In a typical year, fewer than 1,200 people nationwide complete training that qualifies them for nuclear reactor operations. Semiconductor processing graduates number only in the hundreds.

Are Schools Keeping Up with Employer Demand?

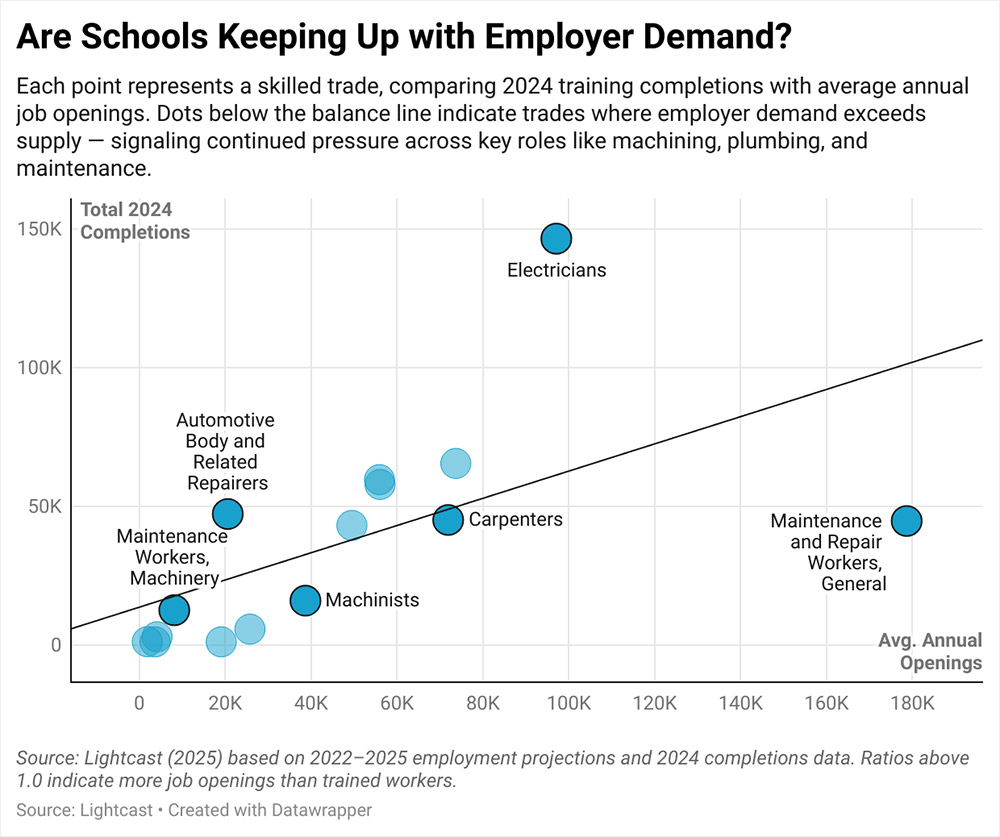

When job openings are plotted against 2024 completions — including both college and registered-apprenticeship output — most occupations fall far below equilibrium. Maintenance workers, machinists, and power technicians show gaps no single state can close alone.

Companies are betting billions on facilities but struggling to find the people who can staff them.

“Our challenge isn’t just finding workers — it’s reaching them early enough,” Loyack said. “We’re now taking workforce awareness all the way back into middle schools. Businesses like Eli Lilly and Pratt & Whitney are helping us design curricula that introduce manufacturing and biotech careers before students even enter high school.”

That early intervention is key to aligning future supply with industry demand, he added. “Employers aren’t just looking for entry-level workers anymore,” Loyack said. “They need people who can keep up with automation, AI, and leadership training throughout their careers. That’s why community colleges are pivoting to short-form microcredentials and modular learning — it’s about meeting businesses where they are.”

To explore how states are responding, Area Development will also examine programs like Texas State Technical College — which ties funding directly to job placements — and Maricopa Community Colleges in Arizona, a national model for semiconductor workforce training.

The Policy Paradox: Investment Without Capacity

Federal incentives are unlocking massive private investment — more than $850 billion in announced manufacturing projects since 2021 — but the education system operates on a slower cycle.

It takes months to finance a facility, years to build it, and a decade to rebuild a technical workforce pipeline.

“Roles are becoming more sophisticated, and it’s not just about filling jobs anymore — it’s about matching aptitude and adaptability,” Nicole McBride said during a recent interview with the Area Development podcast. “That’s why we’re seeing a shift toward more modular training and short-form credentials that align with how technology is transforming the factory floor.”

Limits of the Data — and Why It Still Matters

Even with the inclusion of Department of Labor apprenticeship completions, this analysis captures only part of the training picture. Union programs, employer-run academies, and military-to-civilian transitions often fall outside official data streams.

Workforce readiness now rivals power availability as a top constraint on project timelines.

Many roles in the skilled trades don’t require postsecondary education — just a high school diploma and significant on-the-job training. The Bureau of Labor Statistics lists dozens of occupations, from metal pourers to assemblers, where moderate on-the-job training is the standard. Those workers rarely appear in completion counts, underscoring why even the best datasets can only approximate the real supply of talent.

“No dataset tells the full story, but every indicator points in the same direction,” Wright said. “The competition for skilled labor is real, and it’s intensifying.”

The takeaway: treat these numbers as diagnostic, not discouraging. They pinpoint the pressure points where collaboration among employers, colleges, and governments yields the highest return.

“The shortage of skilled trades is no longer just a labor issue — it’s a location strategy driver. Corporate occupiers and manufacturers are prioritizing regions with strong training pipelines, community partnerships, and incentive programs tied to workforce readiness. Talent sustainability now rivals cost and infrastructure as a top factor in site selection,” Harris said.

The story of America’s industrial comeback is being written in concrete and steel — but its success depends on people.

The same policies fueling billions in investment must be matched with investment in training. For site selectors, consultants, and corporate planners, the new reality is clear: The true competitive advantage isn’t cheap land or fast permitting — it’s a workforce pipeline that works.

If Ford can’t hire at that wage, smaller manufacturers entering the market face even steeper odds. It’s a reminder that the next era of industrial growth won’t be defined by capital alone — but by whether anyone is trained to turn the wrench.