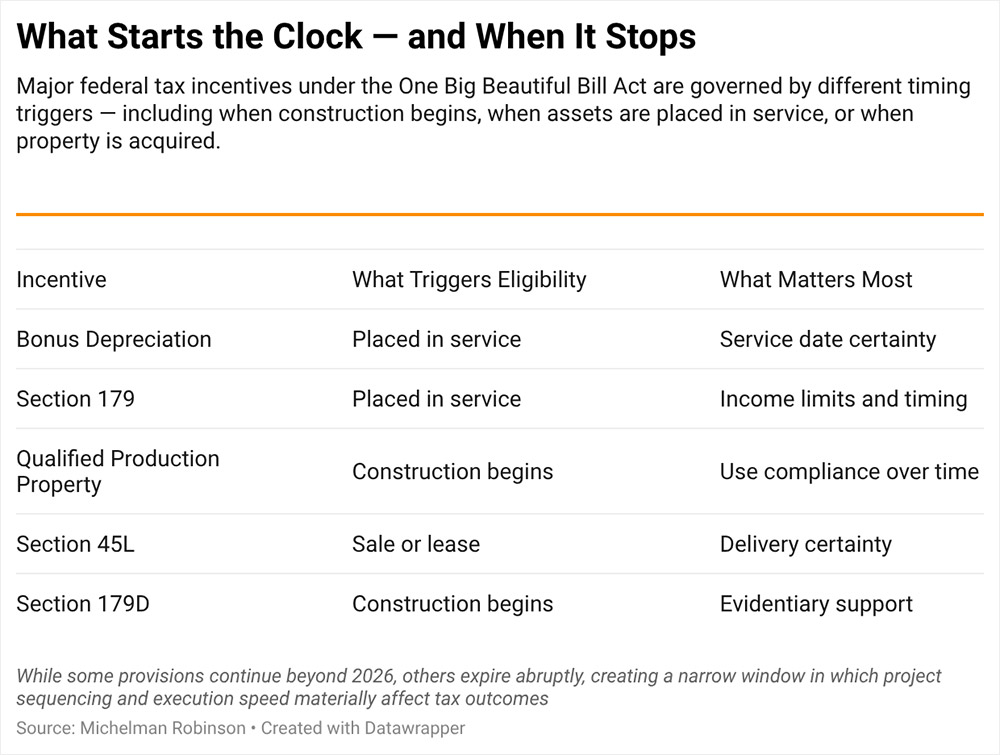

As the 2026 tax season approaches, developers and tax advisers are preparing for the first filing cycle that will fully reflect the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. Signed into law on July 4, 2025, the OBBBA changes the economics of commercial development in ways that are both generous and deadline-driven, expanding front-end deductions while accelerating the expiration of key building-efficiency incentives.

For taxpayers in the know, the 2025 tax year filed in 2026 marks the opening of a rare “golden window”: a short period in which revived capital expensing overlaps with the final months of certain energy-related benefits before a mid-2026 cliff. For the modular sector, the OBBBA is more than a tax cut. It is a policy environment that rewards speed, documentation and disciplined classification, all areas where modular projects can hold a practical advantage when tax planning matches build strategy.

Bonus Depreciation and Expanded Section 179

The OBBBA’s most immediate impact is the restoration of bonus depreciation. Under the phase-down schedule following the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, bonus depreciation was shrinking, dropping to 60 percent in 2024 and 40 percent in 2025. The OBBBA halted the decline. For qualified property acquired after Jan. 19, 2025, and placed in service in the applicable taxable year, bonus depreciation is restored to 100 percent, subject to statutory timing rules, transition elections and special rules applicable to self-constructed property.

The real advantage is not a label; it is the ability to build a credible record and place assets in service on a predictable timeline.

The new law also expands Section 179, increasing the expensing cap to $2.5 million and the phaseout threshold to $4 million. For middle-market operators deploying modular solutions, guardhouses, administrative space, medical clinics and other specialized facilities, this can translate into meaningful Year 1 deductions for qualifying property placed in service, assuming the taxpayer can utilize the deduction under applicable income and entity-level limitations.

Together, these provisions can materially improve early-year cash flow. But the OBBBA’s most attractive outcomes are not automatic. They depend on what qualifies, how costs are classified and whether the taxpayer can support those positions if challenged.

Modular Edge

Modular construction is not automatically treated as tangible personal property, and taxpayers should be skeptical of any plan that assumes the building itself becomes expensable simply because it was assembled offsite. Nonresidential real property generally remains subject to a 39-year recovery period, regardless of delivery method.

Where modular can outperform is in the practical conditions it creates, namely compressed schedules, reduced onsite variability and clearer component-level procurement records. Those features can support more defensible cost allocations into shorter-lived categories, often through a rigorous cost-segregation approach, especially where projects include systems and assets that may qualify for shorter recovery periods and potentially for immediate expensing under bonus depreciation when properly substantiated.

100%

In narrower situations, particularly where units are genuinely designed and used as relocatable, arguments for personal-property treatment may be supportable. But those outcomes are fact-specific and should never be presumed. In the OBBBA era, the real advantage is not a label; it is the ability to build a credible record at the component level and place assets in service on a predictable timeline.

Classification Discipline: What the IRS Will Expect to See

The IRS distinguishes real property from tangible personal property through a multifactor, fact-intensive analysis that often considers permanence, the manner of affixation, intended duration of use and the practical consequences of removal. In that framework, an all-or-nothing claim that an entire modular facility is equipment is typically the most vulnerable posture.

Modular construction does not turn buildings into equipment, but it can make classification more defensible.

A stronger approach is usually component-based: classify assets by function and integration, supported by coherent project documentation and an engineering-driven methodology. Authorities commonly relied upon in this area, including Hospital Corporation of America v. Commissioner, 109 T.C. 21 (1997), reinforce the proposition that classification turns on functional use rather than form or marketing characterization.

If relocatability is intended to matter in the analysis, it should appear consistently in the project’s facts: design choices such as demountable connections, foundations engineered for removal where feasible, operational plans and records that align with the claimed use. These factors can strengthen the case, but they do not eliminate the need for disciplined cost-segregation support and audit-ready documentation.

Qualified Production Property: A New Tool for Industrial Expansion

The OBBBA also introduces Qualified Production Property, which in defined circumstances can extend 100 percent expense treatment to certain production-related real property where construction begins after Jan. 19, 2025, and before Jan. 1, 2029, and the property is placed in service before Jan. 1, 2031, provided the property is an integral part of qualifying production activity. For manufacturers expanding domestic operations or industrial clients building facilities integral to qualifying production activity, QPP may materially improve cost recovery and narrow the historic gap between walls and machines.

QPP is definition-driven, compliance-intensive and subject to recapture if the property ceases to satisfy statutory use requirements during the applicable compliance period. Properly applied, it can be powerful; applied casually, it can create risk that lingers well beyond the year of construction.

The June 30, 2026, Cliff: Two Incentives, Two Different Timing Standards

The OBBBA also accelerates the expiration of two major building-efficiency provisions: Section 45L, the New Energy Efficient Home Credit, and Section 179D, the Energy Efficient Commercial Buildings Deduction. Both sunset June 30, 2026, but the timing rules differ, and that difference will shape project sequencing.

June 30, 2026

For Section 45L, eligibility generally turns on whether a qualified home is acquired through sale or lease, consistent with program requirements, by the deadline. The credit is often discussed as up to $2,500 to $5,000 per unit, depending on the qualification pathway and applicable requirements, but the practical issue is schedule certainty. Traditional multifamily projects may face material risk of missing the acquisition deadline. Modular projects, because they compress schedules and reduce variance, are often better positioned to deliver and document qualifying acquisition events within the window.

For Section 179D, the sunset is keyed to whether construction begins by the deadline. Projects that satisfy the standard may be grandfathered into the deduction regime, subject to statutory requirements and future guidance. Taxpayers may look to “begin construction” concepts used in other federal incentive regimes as reference points, but prudent counsel should treat this as an evidentiary standard rather than an assumption, particularly until Treasury and IRS guidance clarifies how the rule will be applied here.

Supply Chain Compliance: A Smaller Section With Bigger Consequences

The OBBBA also underscores an industrial-policy reality: incentives increasingly come with supply chain and counterparty scrutiny. Domestic-content rules are credit-specific, but where they apply, taxpayers may need substantiation that structural steel and iron manufacturing processes occur in the U.S. and that manufactured products meet evolving domestic-sourcing thresholds often measured through cost-based tests.

Incentives reward speed and documentation, not assumptions.

Layered on top are restrictions tied to prohibited foreign entities and related foreign-influence concepts that apply on a credit-specific basis, with effective dates and thresholds that vary by regime. In some cases, the risk includes recapture, not just disallowance.

For modular firms integrating sophisticated systems such as storage, controls and high-efficiency HVAC, the takeaway is direct: traceability is now a tax issue. Contracts should allocate compliance responsibility clearly through representations, covenants, audit-cooperation obligations and indemnities aligned with the parties best positioned to manage sourcing risk. Developers should also remain mindful that projects using HUD Community Planning and Development funding may implicate Build America, Buy America Act requirements, subject to implementation rules and available waivers.