The U.S. energy sector is undergoing a historic transformation, driven by soaring electricity demand from new technologies, ambitious corporate sustainability goals, and major federal roadblocks. This has triggered a nationwide land rush, placing real property at the center of the energy transition conversation in the U.S. With the existing grid struggling to keep up with increasing power demands, utilities are aggressively shifting from passive energy procurement to direct real estate acquisition and development. For corporate leaders, understanding this new utility strategy is essential for strategic site selection and competitive positioning.

The Utility Shift to Real Estate and Development

Historically, regulated utilities often met renewable energy needs through long-term power purchase agreements, or PPAs, with independent producers. Today, utilities are increasingly pursuing direct asset ownership.

The primary driver of this shift is that it allows utilities to add the value of a power plant to their “rate base,” which is the value of property on which they are allowed to earn a specified rate of return for shareholders, as set by a public utility commission. Power purchased from others is merely a pass-through expense, offering no such return.

Direct ownership also gives utilities greater control to meet state and federal decarbonization mandates, improve grid reliability, and stabilize long-term prices. This allows them to capture the full project value, including energy, capacity payments, and renewable energy certificates. Consequently, utilities are now competing directly with power producers and commercial developers.

A Comparative Analysis of Key Transaction Models

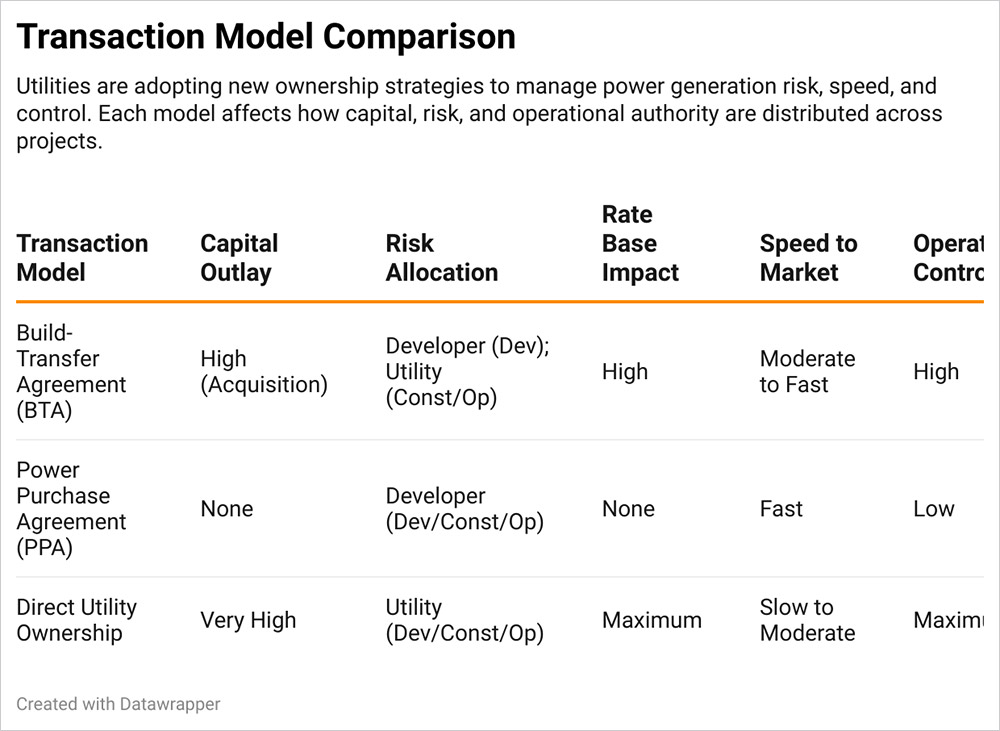

The decision to build, buy, or simply contract for power is a complex one, forcing utilities and developers to weigh the trade-offs between risk, control, capital investment, and speed. Various transaction model options exist because there is no one-size-fits-all solution; each structure allocates critical variables differently to suit a company’s specific financial situation, risk appetite, and strategic goals.

960

While no single model is universally preferred, regulated utilities are showing a distinct preference for structures that result in asset ownership — such as direct ownership or build-transfer agreements — because of the powerful incentive to grow their rate base. A build-transfer agreement, or BTA, is a hybrid model where a developer handles the high-risk early stages of a project, such as obtaining site control and permits, before transferring the “de-risked” asset to the utility upon completion. This model leverages developer agility while allowing the utility to add the final asset to its rate base. While this approach mitigates early-stage risk and benefits from specialized developer expertise, it often comes with a higher acquisition cost and requires complex negotiations, especially given current market conditions.

In contrast, entities in deregulated markets or those looking to avoid massive capital outlays continue to rely heavily on the flexibility of power purchase agreements. PPAs remain a common model where a utility or other large electricity consumer buys power from a project owned and operated by an independent power producer for a long term, typically 15–25 years. This allows the power purchaser to avoid all development and operational risk and requires no upfront capital, providing predictable energy costs. However, for a utility, this path forgoes the opportunity to expand its rate base, offers less operational control, and prevents it from directly monetizing tax incentives.

In the direct utility ownership, or “self-build,” model, the utility acts as its own developer, directly acquiring land and managing the entire project. This approach offers maximum control and rate base value but places all development, construction, and financial risk squarely on the utility and its ratepayers. While it maximizes shareholder return, this model can be slower and less efficient than private development.

Mitigating the Top Three Real Estate Legal Challenges

Whatever transactional model utilities choose, proactive risk management is essential for project survival. Energy projects are defined by massive upfront capital investment and long, complex development timelines where real estate is the most critical component. Failing to proactively manage land-related risks means that fatal flaws — such as an undiscovered title defect or community opposition — may only be discovered after millions of dollars have been spent. This reactive approach inevitably leads to crippling delays, explosive budget overruns, and, in a worst-case scenario, the complete abandonment of the project, reducing a promising asset into a substantial financial loss.

First, navigating the zoning and permitting gauntlet is often the most unpredictable part of development due to community opposition and complex regulations. Such opposition and complexity may be mitigated by early and transparent engagement with local officials and community leaders; however, early engagement can be more difficult with a BTA model, where a developer is in control during this phase, potentially leaving the acquiring utility to inherit landowner issues. Success depends on incorporating local zoning codes into initial site screening and utilizing state-level siting authorities where available to streamline approvals.

Power is no longer a commodity — it’s a site-selection constraint.

Second, securing necessary land control is paramount, as unforeseen issues can present fatal flaws to a project. Obtaining option agreements creates site control with minimal upfront capital while also providing a crucial window for due diligence before committing to a long-term agreement. It is also vital to obtain comprehensive land title surveys and proactively negotiate with existing mineral rights holders, a challenge particularly pronounced in states with a long history of oil and gas activity.

Third, navigating landowner relationships from negotiation to operation is critical. Unlike a one-time purchase, an energy project creates a long-term partnership, often spanning 20–40 years or more. A failure to establish a clear and fair agreement at the outset can lead to persistent operational friction and ongoing community opposition. Conflicts can arise over issues not clearly defined in the initial lease, such as maintenance, interference with farming activities, and access rights.

2.5

A comprehensive lease agreement, negotiated with transparency, is the foundational document for a lasting relationship. This includes clearly defined compensation with escalator clauses, precise mapping of land use and access rights, and explicit reservation of the landowner’s rights on adjacent property. Proactive operational management, including a designated local point of contact and clearly delineated maintenance duties, can also be beneficial. Finally, planning for decommissioning from the start, with a detailed plan and financial guarantee for land restoration, builds crucial long-term trust.

The race to electrify is becoming a race for land.

A C-Suite Guide to Site Selection in the New Energy Paradigm

For corporations planning energy-intensive facilities, the site selection playbook must evolve because the energy landscape itself continues to change focus. Power is no longer a simple commodity; it is now the primary gating factor for any major industrial development — especially as the race to build AI data centers increases demand for electricity. Corporations that adapt their strategies to treat energy as a critical strategic asset can secure a powerful competitive advantage, enabling faster construction and more reliable operations. Failing to evolve risks being saddled with sites that cannot be powered on a viable timeline, leading to catastrophic project delays, stranded capital, and a loss of market position.

Power availability is now the primary factor determining a site’s viability. With grid capacity constrained and interconnection queues backlogged for years, the “time to power” can make or break a major investment. Site selection teams should perform deep diligence on a location’s energy readiness by analyzing the local utility’s integrated resource plan, investigating the regional grid operator’s interconnection queue, and understanding the utility’s preferred transaction models to predict its behavior.

Bringing your own power is the new competitive advantage.

This reality has given rise to the “Bring Your Own Power” imperative, where leading corporations develop on-site generation to ensure power reliability. This strategy requires much larger land parcels that can host both an industrial facility and a power plant, creating a new premium class of “energy-anchored” industrial real estate. Two recent examples highlight this shift. First, Amazon Web Services acquired a 1,200-acre data center campus in Pennsylvania directly connected to a 2.5 GW nuclear power plant, securing up to 960 MW of reliable, carbon-free power through a long-term PPA. Second, Microsoft, as part of its goal to eliminate diesel backup generators by 2030, successfully tested hydrogen fuel cells to power a row of data center servers for 48 consecutive hours, proving the viability of clean hydrogen for providing uninterrupted power.

As corporations navigate this new landscape, executives must integrate an energy-first mindset into their planning. This involves elevating energy to a core business strategy, embedding deep energy diligence at the outset of site selection, future-proofing real estate acquisitions by prioritizing larger sites, and proactively engaging with utilities as strategic partners to understand long-term infrastructure plans.