SETTING THE STAGE

2025 continues to be a whirlwind of global trade developments. Yet in spite of all of the surprises defining this year, one trade issue is certain: renegotiation of 2020’s United States-Mexico-Canada Free Trade Agreement (USMCA). Although a review and potential renegotiation are scheduled to occur by July 2026, there is potential for this to begin by late 2025.

What is less certain is what a renegotiated agreement may look like. The U.S. administration’s first tariff announcements targeted Canada and Mexico (in addition to China), kicking off a circuitous path of announcements, pauses, exemptions, and tariffs that have generated hard feelings and a persistent environment of uncertainty.

The core fundamentals of the North American economy are at stake. Agricultural goods, energy, construction materials, and automotive manufacturing are only a few of the critical sectors at risk. Long-established supply chains in smaller sectors can be disproportionately reliant upon USMCA trade as well, exposing direct risks for many industries.

PATHS TO CONSIDER

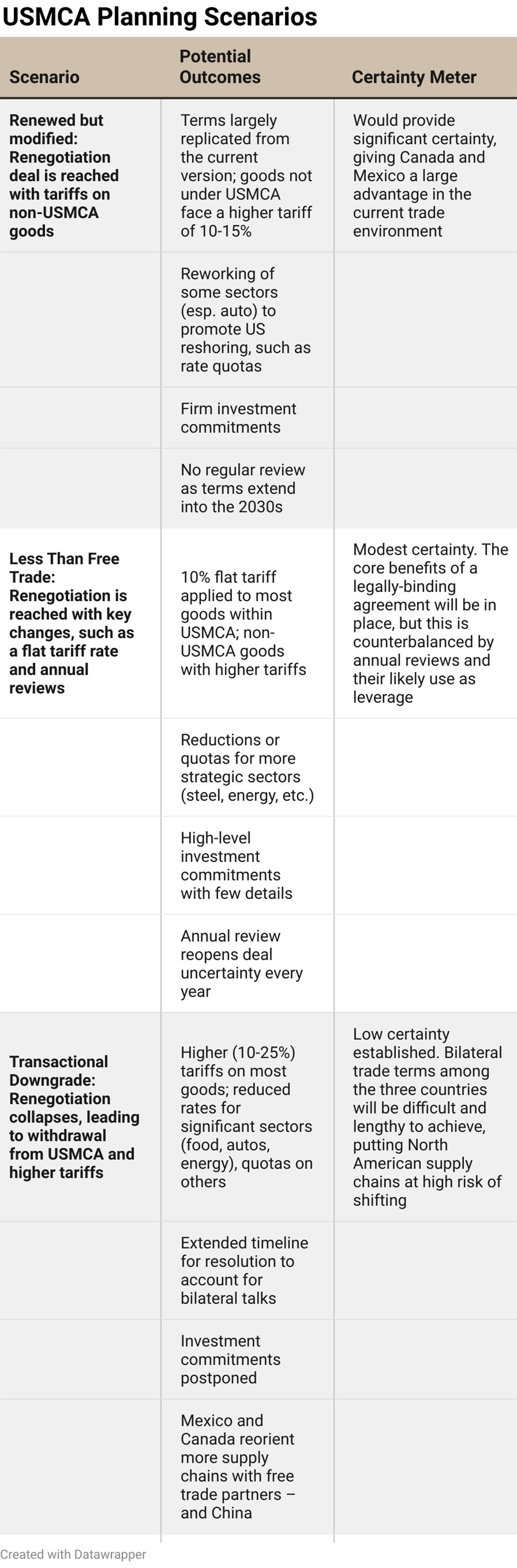

There are three basic outcomes. In the first, the USMCA could be renewed for another 16 years. Another result could be renewal through 2036 but with annual reviews by the U.S., Mexico, or Canada. Lastly, any of the participating countries may formally withdraw within six months, effectively collapsing the agreement. Investors and communities should be well on their way with preparation for different outcomes of these talks. Some potential scenarios can help inform what these might look like.

Renewed but Modified

A renegotiation deal is reached with tariffs on non-USMCA goods. Terms would largely replicate the current version, with goods not under USMCA facing a higher tariff of 10 to 15 percent. Certain sectors, especially automotive, could be reworked to promote U.S. reshoring, such as through rate quotas. The deal would include firm investment commitments and no regular review as terms extend into the 2030s. This scenario would provide significant certainty, giving Canada and Mexico a large advantage in the current trade environment.

Tariffs may again become the price of doing business across North America.

Less Than Free Trade

A renegotiation is reached with key changes, such as a flat tariff rate and annual reviews. A 10 percent flat tariff would be applied to most goods within USMCA, with non-USMCA goods facing higher tariffs. There could be reductions or quotas for more strategic sectors such as steel and energy. High-level investment commitments would be made with few details, while annual reviews would reopen deal uncertainty every year. This scenario provides modest certainty. The core benefits of a legally binding agreement would be in place, but this is counterbalanced by annual reviews and their likely use as leverage.

Transactional Downgrade

Renegotiation collapses, leading to withdrawal from USMCA and higher tariffs. Tariffs of 10 to 25 percent would apply to most goods, with reduced rates for significant sectors such as food, autos, and energy, and quotas on others. There would be an extended timeline for resolution to account for bilateral talks, and investment commitments would be postponed. Mexico and Canada could reorient more supply chains with free trade partners—and China. Low certainty would be established. Bilateral trade terms among the three countries would be difficult and lengthy to achieve, putting North American supply chains at high risk of shifting.

WHERE DO COUNTRIES STAND

Both Mexico and Canada have been preparing by demonstrating their commitment to U.S. political priorities. Mexican leadership adjusted policies on immigration, organized crime, and Chinese imports to accord with U.S. priorities. Outrage in Canada with U.S. administration actions and language has challenged bilateral relations, but the Canadian government has largely aligned with its neighbor on economic and border control policies.

33

For now, leaders of both of these countries enter the USMCA renegotiations in positions of strength. They were elected relatively recently and have political support to advocate aggressively for national trade interests. The perception of coming under threat by the U.S. has also generated broader public support for Canadian and Mexican leadership. And recent, high-level coordination between the two countries has confirmed a desire to work more closely in the lead-up to USMCA talks.

The U.S. is the key actor in these talks. The U.S. administration has shown a willingness to seek out and utilize trade leverage to maximize gains, largely in the form of tariffs and foreign investment commitments. With the U.S. Congress removing itself from the trade conversation, the administration has had considerable leeway to determine trade matters as it sees fit. In order to qualify as a legally binding trade agreement, a renegotiated USMCA will need to be approved by Congress. However, the U.S. administration has repeatedly been able to convince its legislative majority, however slim, to support its priorities.

The real risk isn’t failure—it’s prolonged uncertainty.

WHAT CAN WE EXPECT

Rhetoric during the talks is likely to be heated as positions are not aligned. Canada and Mexico are firmly in favor of renewing USMCA and its tariff-free terms as much as possible. As such, they have both made conciliatory moves toward the U.S. vis-à-vis China and migration. The U.S. administration, on the other hand, is interested in reducing trade deficits (as the U.S. has with Canada and Mexico) and an increase in U.S.-based manufacturing. Tariffs are the preferred tool for the U.S. administration to reach these goals and may well be an end in and of themselves. With Mexico and Canada aligned with the status quo and the U.S. in favor of new terms, the U.S. position will be the key to success or failure in USMCA renegotiations.

Hard numbers may ultimately encourage all sides to reach some agreement. Per the U.S. Trade Representative, exports to the U.S. are core to Canadian and Mexican economic growth, making up 75 percent and 80 percent of all of their exports, respectively. This reliance on the U.S. is not lost on the American administration. At the same time, 33 percent of U.S. exports head to Mexico or Canada, making them not only the top two destinations but also more than the next nine countries combined. Key U.S. sectors—construction, agriculture, automotive, and many others—are reliant upon USMCA supply chains.

2026

The status of economic indicators may inform negotiating positions as well. Growth in the U.S. is a positive signal, but negative consumer outlooks echo slowdowns in manufacturing, labor, and inflation reduction. Similarly, growth in Mexico and Canada amidst trade disruptions belies negative outlooks into 2026. A slowdown among any of the three countries could incentivize a new, growth-oriented USMCA.

One factor that complicates trade negotiations is the U.S. administration’s emphasis on incorporating political issues into economic issues. The “weaponization” of economic tools has risen in prominence in recent years, and the White House is expanding on that trend by utilizing tariffs to serve political goals. Few examples are more prominent than the use of the drug trade and illegal immigration as reasons for tariffs on Canada and Mexico. Whether the U.S. is satisfied with bilateral collaboration on these issues or not will be a critical aspect.

Even close trade partners like Canada and Mexico may not escape new U.S. tariffs.

Evidence from this year’s tariff deals offers clues on what a deal could look like. The parameters of announced deals are often slimmer than initially suggested, easing the prospect for agreement. While these agreements have not been formally approved by Congress, as is typical for U.S. trade deals, it is worth noting that participating sides have honored their stated commitments. Announced investment figures by trade deal countries have remained just that—announcements—and scant details do not inspire confidence at this stage. And no country has escaped with zero U.S. tariffs, as even close partners like the United Kingdom face a minimum 10 percent tariff rate.

Could we end up with a new USMCA that echoes this framework? What these factors underscore is the lack of certainty compared to the trade deals of years past, including USMCA and its predecessor, the North American Free Trade Agreement. The biggest risk may not be that talks fail, but that they extend uncertainty—mandating an annual review, for example, or making facets of an agreement conditional upon a future, opaque target, such as inbound investment. The relative stability of any agreement, however limited, may be the best outcome in the current environment.